Book review: The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind, by Martin Sixsmith

With his extensive experience as a journalist and foreign correspondent, in Moscow and Washington amongst other assignments, and his more recent qualifications as a psychologist, Martin Sixsmith brings a fascinating perspective to this study of the tensions and paranoia of the Cold War.

As we might expect, his book begins at the end of World War II, with Churchill, Stalin, Roosevelt and then Truman conferring about the future. I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised that Churchill and Roosevelt had psychiatric support and therapy. I was more surprised to learn that Stalin had a neurological and psychological examination in 1927 by the head of the Congress of Russian Neurologists and Psychologists, Vladimir Bekhterev. According to Sixsmith, “No record of the meeting survives, but when Bekhterev returned to his colleagues he declared, ‘I have just examined a paranoiac with a small, dry hand.’ Twenty-four hours later he was dead.”

Advertisement

Hide AdStalin looms over the first hundred or so pages, but the book’s focus is not on the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union but on more general aspects of “the mind” during the Cold War. True, we learn much about what made Kennedy, Khrushchev, Nixon, Reagan and Gorbachev tick, but we also learn how military personnel coped with managing weapons that could kill hundreds of thousands of people, and how the threat of nuclear annihilation played on the minds of people in the streets of Chicago or Leningrad. Propaganda and disinformation were used to discredit the culture of “the enemy” and it is disquieting to learn, for example, that Joseph McCarthy fulminated against cures for polio and lambasted gay men and women as he sought out “communists” in the United States government. Similarly, in the Soviet Union in the 1980s there were posters suggesting that AIDS had been created in laboratories at the Pentagon.

There are fascinating chapters on the films, books, music and art on both sides of the Iron Curtain, as well as Soviet and East European jokes. Sometimes this material is amusing, but less so are the chapters on the mental suffering experienced in the Warsaw Pact countries, particularly East Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

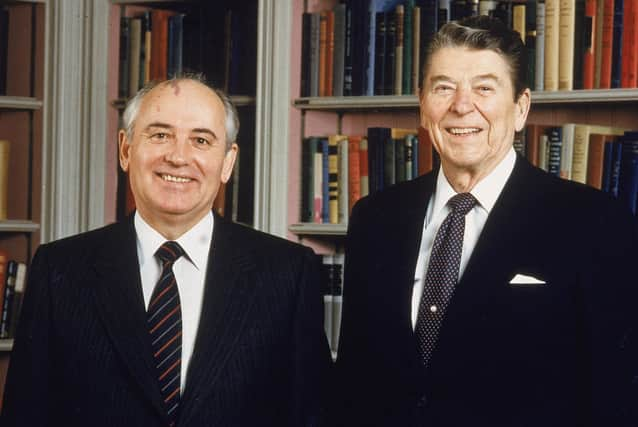

There is no mention of Scotland’s role in the ending of the Cold War, but perhaps this could have been woven into Sixmith’s thesis. During the 1980s there was a series of informal meetings, “The Edinburgh Conversations”, between Scots and Russians, led first by Ritchie Calder and then by Professor John Erickson, in which ways of ending the nuclear standoff were discussed. A small group of academics and retired army officers, not delegates or officials but specialists, chewed over the problems. A defence historian and fluent Russian speaker, Erickson was respected by the Soviet military establishment, and he understood their thinking and ways of working. It was the Edinburgh Conversationalists who came up with the statement “No First Strike”: neither side would be the first to launch a nuclear strike against the other. This was to underpin the 1985 Geneva meeting between Reagan and Gorbachev, and became the foundation for the later summits and agreements.

Sadly, the hope that came from the Reagan/Gorbachev agreements faded away, the idea of a peace process being replaced by the triumphalism of Reagan’s successor, George Bush senior. This, with the collapse of the USSR and the chaos of the Yeltsin years has led, if not to a new Cold War, then certainly to new tensions. This book is resonant about the psychology of contemporary international relations, too. To what extent does Washington understand Moscow today, or Beijing, for that matter?

The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind, by Martin Sixsmith, Profile Books, 577pp, £25

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions