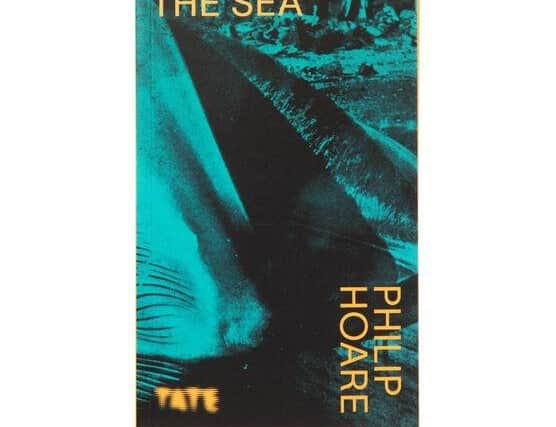

Book review: The Sea, by Philip Hoare

It’s traditional, in some parts of Scotland, to begin the New Year with a swim in the sea. Sadly, with only the humble medium of the written word at my disposal, I’m not able to offer anything quite so bracing to kick off 2023. However, thanks to Philip Hoare, who has just released a new book exploring the relationship between the sea and the visual arts, we can at least dip a metaphorical toe into the brine.

Simply titled The Sea, Hoare’s latest is part of the Tate galleries’ Look Again series. These short books, written by a wide range of experts on themes such as Fashion, Visibility and Complicity, are intended to “open up the conversation about British Art”, drawing on the Tate’s extensive collection for examples. Hoare has previous when it comes to documenting the intersection between culture and the Big Blue. Books published to date include Leviathan, or the Whale, which combined a history of whaling with an exploration of the life of Herman Melville, and The Sea Inside, for which the author stravaiged around the world, swimming with whales and dolphins. An academic at the University of Southampton, he lists his research interests as “The cultural and emotional inter-relationship of the sea, the human and the animal”. Fair to say, then, that the Tate project falls very much in his wheelhouse.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe begins his voyage through sea-inspired art with William Blake’s striking monotype of the scientist Isaac Newton, first completed in 1795, then reworked and reprinted in 1805. Sitting naked on a rocky seat at the bottom of the ocean, and armed only with a pair of compasses and a (presumably waterproof) scroll of paper, Newton is – as Hoare puts it – “clearly more concerned with measuring his theories than witnessing the wonders of the deep.” Exotic-looking sea creatures may be footering around by his ankles, but Newton is too laser-focused on the scientific work at hand to notice. This rather snide take on the great scientist, Hoare suggests, is in keeping with the view of Blake’s Romantic contemporaries Byron, Shelley and Keats: that the sea should be seen primarily as a source of wonder, rather than the object of scientific inquiry.

From here, we vault forward in time to the great sea scapes of JMW Turner, notably Whalers, c.1845. Again, Hoare is excellent on the rich and complex set of connections linking art and literature. Turner’s paintings (which were themselves painted in pigments mixed with whale oil) had a profound impact on Herman Melville, who went on to write the greatest whale book of them all, Moby-Dick. There are also illuminating sections on the kindred Surrealist spirits Eileen Agar and Paul Nash and, more recently, the whale-related output of Colin Self, Angela Cockayne and Maggi Hambling. It’s all fascinating stuff, all beautifully written, and yet, and yet…

A friend of mine used to work as a civil servant in Whitehall, and now, whenever he’s looking to illustrate the tendency of London-based decision-makers to overlook the three smaller countries that make up the United Kingdom, he delights in telling the story of the colleague who had a bright yellow Post-It note stuck permanently to the side of his computer monitor. Written on it, in faded ink, were the words "Don’t forget about Scotland."

It’s a pity they don’t have a few of those Post-It notes dotted around the office at Tate Publishing. If they did, somebody might have read Hoare’s manuscript, realised that the lack of artists from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland wasn’t necessarily going to help ”open up the conversation about British Art”, and quietly suggested a bit of a re-think. As things stand, however, anyone reading this (admittedly slender) book will be left with the impression that the only British sea art worth worrying about has been produced in England.

To be fair to Hoare, in order to fulfill his brief he could only write about works in the Tate’s collection. So, even if he’d wanted to include, for example, a few lines on the importance of the west coast seascapes of SJ Peploe and the Scottish Colourists, he couldn’t have done so: according to the Tate website, the only Peploe they have in their collection is Tulips, 1923.

Still, as Scotsman art critic Duncan Macmillan is fond of saying, nobody else is going to tell the story of Scotland’s art for us, and what a must-see blockbuster an exhibition of Scottish sea art could be – not just Peploe and friends, but Joan Eardley’s Catterline pictures, William McTaggart’s epic seascapes, the mystical sea-inspired assemblages of Will Maclean, not to mention the miniature sea paintings of David Cass, the storm paintings of Ross Ryan, the underwater flotsam photographs of Janeanne Gilchrist and Mike Guest’s Dawn Days video project. And, of course, any such exhibition would have to include the nautically-themed works of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Some of these would probably need to be borrowed from the Tate, though – it seems they have 167 works by him in their collection.

The Sea, by Philip Hoare, Tate , £10