Book review: The Last Colony, by Philippe Sands

It was in 1962 that the former American Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, delivered his famous comment that Britain had “lost an Empire, but not yet found a role”. The remark hit home, causing a substantial ripple in the normally calm surface of postwar British-American relations; but even Acheson himself might have been surprised to find that the UK’s struggle to move on from its imperial past is still being played out today, a full 60 years on.

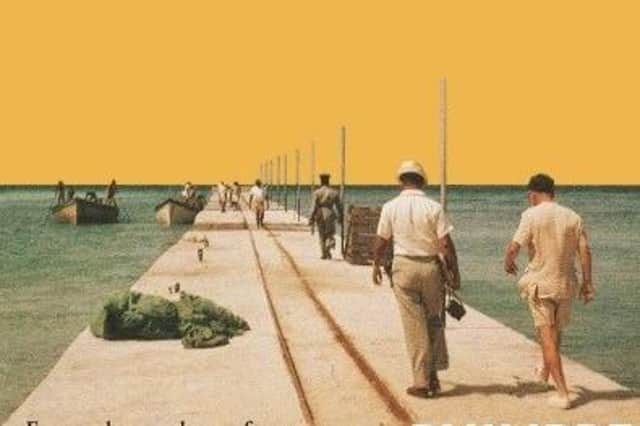

Philippe Sands’s new book The Last Colony – subtitled A Tale of Race, Exile and Justice, from Chagos to The Hague – tells the story of the last six decades of British rule in the Chagos Islands of the Indian Ocean, and of the long legal struggle to free the islands from British rule, after they were summarily separated from the rest of Mauritius, and kept under direct British control, on the eve of Mauritian independence in 1968. It is a tale of lingering colonial attitudes not only to the territory of the Chagos – including the island of Diego Garcia, leased to the United States since 1966 as their principal Indian Ocean air base – but, most shockingly, to the people of the islands, who were forcibly deported between 1967 and 1973, and forced (with minimal compensation) to make new lives in Mauritius or the UK.

Advertisement

Hide AdBoth of these moves – the separation of the islands from Mauritius in order to avoid decolonising them, and the forced deportation of their people – were of questionable legality from the outset; indeed Britain effectively conceded as much back in 1965, when – faced with a damning UN resolution – they promoted the fiction that the Chagos Islands had “no permanent population”, a straightforward lie designed to deflect the accusation of forced deportation.

Sands’s story therefore brings together two strands: the story of the islanders themselves and of the beloved homeland they were forced to leave behind, and the surprisingly gripping narrative of how the evolving international institutions put in place after the Second World War – particularly the International Court of Justice at The Hague – gradually came to grips with their case, finally, in 2019, delivering a devastating judgment against the United Kingdom, affirming the status of the islands as part of Mauritius, and also affirming the right to return of the people forcibly deported 50 years earlier. Sands’s chosen voice of the Chagossians belongs to Liseby Elyse, a woman who was deported from the Chagos as a 20-year-old bride in 1973; and at times, she and her family come to seem like co-authors of the book, the truth of their lived experience ringing out against the decades of official lies, and arcane legal arguments.

Powerful illustrations by the cartoonist Martin Rowson – picturing a small woman in black gradually advancing towards the Great Hall of Justice in The Hague – add an extra edge of vividness to the story; and Sands writes fluently and passionately throughout, linking the story of the Chagossians to the wider narrative of the end of colonialism, and postwar attempts to codify and enforce the right of self-determination of peoples. He also makes clear the extent to which the collapse of British statecraft in recent years, amid the chaos of Brexit, has weakened the UK’s international position and forfeited the support of European allies; a humiliation now made worse by the flat refusal of the British government, sine 2019, to implement the Court’s clear ruling on the future of the Chagos.

The Chagos are not the UK’s “last colony” of course. There are still 15 others, many of them now notorious tax havens; and recent retro-nationalist British governments seem, if anything, to be trying to reinforce old colonial attitudes, rather than to leave them behind. It would be comforting to feel that the long slow journey towards a viable system of international justice chronicled by Sands is marching on regardless, leaving such reactionary and disgruntled governments behind; although sadly, the sheer scale of he global crises we now face make further progress seem increasingly unlikely. This elegant, moving and profoundly informative book comes as a reminder, though, of how much has been achieved in our international institutions, in the years since 1945; and how much we stand to lose, if that history of progress now begins to be reversed.

The Last Colony, by Philippe Sands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 224pp, £16.99. Philippe Sands is appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 28 and 29 August