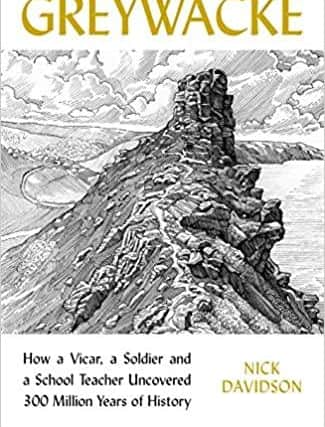

Book review: The Greywacke, by Nick Davidson

There is a curious phenomenon which I now think of as the Suicide Squad conundrum. When I saw the trailer for the 2016 film, I was really rather excited. Then I saw the actual film and it was a load of old cobblers. Sometimes the pitch is better than the product. This book conforms to that. The title is intriguing and enigmatic – what is the greywacke? The glossary gives a good summary: “originally a Victorian catch-all term used to describe unmapped ancient rocks found across Europe including, in Britain, large areas of Wales, Scotland, the Lake District and the West Country. Also known as Transition Rocks. Today the term refers to sandstone rocks composed of a jumble of different grain sizes.”

So, a book on geology, which interests me, given that “My Love is like a red, red rose” touches on the debate between the “plutonists” and the “neptunists” with its melting rocks and seas going dry, and Scotland’s greatest 20th century poet, Hugh MacDiarmid, wrote the masterful “On A Raised Beach” – a poet who could get away with starting a work “All is lithogenesis or lochia.” The cover of The Greywacke teases in its subtitle, “How a Priest, a Soldier and a School Teacher Uncovered 300 Million Years of History” and with an endorsement that this is a “colourful and joyous romp.” Well, I must have been doing my romping all wrong.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe trio in question are Adam Sedgwick, a depressive clergyman and professor who now has a museum collection named after him in Cambridge; Sir Robert Murchison a bombastic failed soldier who became President of the Royal Geological Society and a member of Russia’s Imperial Academy of Science; and Charles Lapworth, a teacher from the Borders whose wife created a “geological waist coat” for him. One can never have too few pockets.

My first twinge of concern came reading the dustjacket. “In the mid-19th century British geology was an intellectual backwater, trailing its Continental masters.” This is a bold statement and to my mind an erroneous one. James Hutton’s Theory Of The Earth may have been late 18th century (with its memorable phrase “there is no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end”, which rather nixed Bishop Ussher’s idea that the world came into being in 4004 BC); but the 19th century had seen figures as significant as Charles Lyell, whose Principles Of Geology was published between 1830 and 1833.

The elements of a good book are here. Sedgwick and Murchison were allies who developed enmities. Lapworth, whose work was done after the deaths of both, was diligent and outwith their circles. Murchison comes across as a singularly dislikeable figure, who took credit for the work of others and constantly referred to his geological surveys in military terms, even creating the designation “Silurian” as considering “Siluria” as a kind of academic personal fiefdom. Poor Sedgwick, with his ecclesiastical and academic duties, did not get around to publishing a major work, and could not compete with Murchison’s panache. Lapworth was afflicted by mysterious ailments.

The book relies on the old biographical trick of saying but not saying: “We will never know exactly what happened. Was it the result of overwork or an infection?” You could create dozens of other hypotheticals to no demonstrable gain.

All books have their own bad consciences, and in this one it comes through a comment on Murchison’s magnum opus. “Did your eyes ever light upon such a mortal mass of heavy writing and dry profitless mineralogical detail as contained in Part 1 of The Silurian System?” Put that in parallel with sentences such as “Sedgwick was less concerned about Carboniferous fossils in the Greywacke, but was under growing pressure to back his stratigraphic classification of the Cambrian strata with at least the outline of a fossil fingerprint. Given the almost complete absence of Cambrian fossils in Wales, he fervently hoped that the apparently equally ancient rocks in Devon and Cornwall would yield a better harvest”. Glazing over is permitted.

Popular science is, I would aver, the most difficult of genres. It has to combine big ideas with human interest, and on occasion there is a chink of that here. The principal characters are sketched but rarely fleshed, except when you light upon a detail like Sedgwick complaining that “mustard footbaths and mustard chest cataplasms were all in vain” and that he suffered from “strange clouds of oblivion”. The book does suggest that the human interest might come from the author, but phrases like “such a landscape seize the imagination” hardly seem to draw the reader. Also, in one personal aside, Davidson claims that in Galashiels (where I went to school) “today only the occasional store still sells tweed and kilts to passing tourists.” I’d like to know where this store is, and indeed, where the passing tourists are.

Advertisement

Hide AdStone is interesting. It will last longer than us, and has been here before us. But it requires a degree of poetry to represent that. When, at the end of this book, Davidson writes that he picked up “a tiny fragment of this very ordinary looking rock: dull grey, without any outstanding features” – well, you’d have to have a heart of stone not to think, “yes, right”.

The Greywacke, by Nick Davidson, Profile, £20

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions