Book review: The Dickens Boy, by Thomas Keneally

Edward Bulmer Lytton Dickens, always known by his childhood nickname Plorn, was the youngest of the great novelist’s ten children and was dispatched to Australia to make good just before his 16th birthday. Dickens, either simply to get rid of them or as a way of rounding up a story, had made a habit of sending his characters to the colonies, most notably Mr Micawber in David Copperfield. He did the same with his sons, sending some to India and others to Australia. One, Alfred, was already there when Plorn arrived.

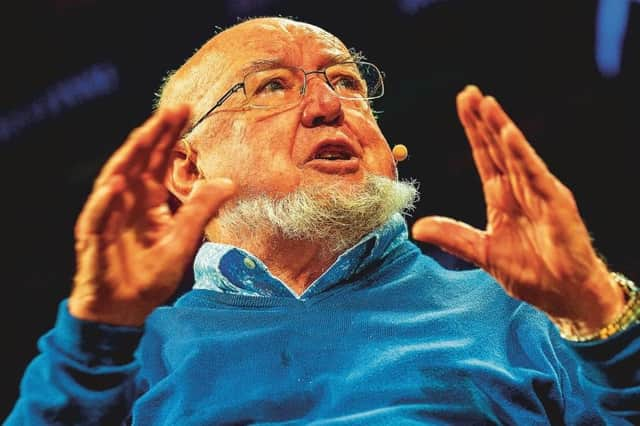

Keneally has Plorn narrate the story of his first couple of years in Australia, working on a sheep ranch. He is an agreeable, ingenuous but also resourceful boy. The story of his encounter with the vast expanse of Australia and the rich variety of its people – colonists, ex-convicts, aborigines, bushrangers and ne’er-do-wells – is engaging. Keneally has always been a wonderful storyteller, a master of the easy-flowing narrative, and even in his ninth decade with more than 30 novels behind him, his energy and inventiveness are unabated. Different strands of the narrative are expertly managed, and the picture of early colonial society, with its hard and often lonely work, its cricket matches and race-meetings, is full of life and very pleasing.

Advertisement

Hide AdYet the novel, like Plorn’s own life, is dominated by Dickens. He is famous as no novelist has been since and wherever Plorn goes he meets people who are his father’s entranced and devoted readers. This is somewhat embarrassing, for the boy has never actually read any of the novels. He loves his father – the “guvnor”– and has rich and happy memories of childhood at Gad’s Hill. He is of course proud of him, but there is a sense that his banishment to Australia is both a test of his manhood and proof of his inability to impress the guvnor.

Plorn, like all his brothers and sisters, is caught in divided loyalties. The very public break-up of his parents’ marriage and the expulsion of his much-loved mother Catherine, now returned to live with her parents, are a source of pain and embarrassment. One of the happier moments is when, visiting his brother Alfred over Christmas, Alfred’s cook makes their dinner from her book of Catherine Dickens’ recipes, adapted to what is available in Australia. But this is followed by an argument with Alfred, who has been drinking heavily, in which the elder brother speaks very critically of their father’s behaviour. Both are also aware of his relationship with the young actress Nelly Ternan, carefully concealed from his adoring public and the press.

Though Dickens appears in the novel only in his son’s memories and conversation, and of course as the world-famous author, the great adored star of literature, his presence in the novel is pervasive. He remains an enigma: benevolent and generous of temper, yet also harsh in his judgement of others, kindly but dictatorial. Dead now for 150 years, he continues to fascinate us, and Keneally seems to me to have come as close as any of the many biographers to elucidating his remarkable character, so full of contradictions.

I confess that when I read the title and realized that the novel was written in the persona of young Plorn, I had an unworthy suspicion that Keneally wanted to write about the experience of a young English boy hurled at the age of 16 into the Outback and varied society of early colonial Australia, and happened on the choice of Dickens’ son as perhaps no more than a peg, good for publicity. Happily the suspicion was almost at once dispelled. It vanished when the manager of the first station Plorn was sent to questioned him closely and disagreeably about the break-up of the Dickens marriage as reported in the press, and Plorn indignantly walked out.

In truth, Keneally has brought off a notable double: a delightful and continuously interesting portrayal of mid-19th century life in the rolling sheep pastures of New South Wales and an acute and persuasive examination of the mystery that Charles Dickens still presents, and of the enduring fascination he exerts over us today.

The Dickens Boy, by Thomas Keneally, Sceptre, 392pp, £20

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

To subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app, visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates

Editorial Director