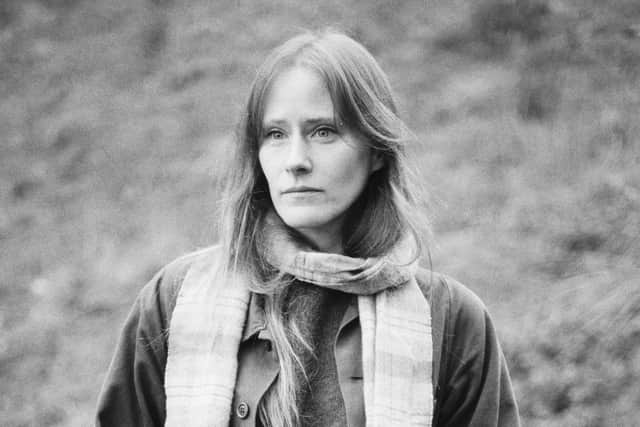

Book review: Study for Obedience, by Sarah Bernstein

Sarah Bernstein, a Canadian who now lives in Scotland, was included in the Granta List (published every ten years) of the 20 best young (that is, under 40) British writers. Study for Obedience is her second novel. The first, The Coming Bad Days, was described by one reviewer as “an example of Millennial Modernism and the difficulty of using language to pinpoint exactly how we are feeling and how we relate to one another”.

Millennial Modernism is a useful expression, but recognition of such difficulties is hardly new; James Kelman, Samuel Beckett, Franz Kafka and Robert Musil being only a few who have posed such questions, often unanswerable. Beckett is among the authors cited by Bernstein in an endnote to her new novel. Another is Montaigne and you might find the roots of such Modernism in his famous question: when he was playing with his cat, could he be sure that the cat wasn’t playing with him? You might even say that the difference between Realism and this sort of Modernism is the difference between dogs and cats.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe narrator – really the only voice in the novella – is a young woman who works intermittently as an audio-typist and is more comfortable with the written word than in speech. She is invited – summoned really – by her oldest brother to his house in the country overlooking a town in the plain below. He is, it seems, a successful businessman, though what his business is never becomes clear. He will go away for some months and when he returns appears to be diminished and mentally disturbed. The house is in high country and seems to have been inhabited by their forebears, later persecuted and killed. Nothing is made clear for at first the narrator writes as if she knows little, even nothing about them. One assumes from the first that they were Jews, and indeed the narrator confirms this when she says she had been a disappointment to her parents and teachers because of her refusal “to say bracha over our classroom Sabbath ceremonies”. This is presumably why she is sure she is regarded with hostile suspicion when she ventures into the town, though this may all be in her vivid and defensive habit of mind.

Indeed, she often says what a disappointment and failure she has been. Yet at the same time her self-absorption indicates a certain complacency. People who parade their thoughts, speaking of their inability to connect to others, as she connects to nobody but her brother, are usually in thrall to their egotism. There is always some self-satisfaction in assertions of insufficiency.

Nor is the narrator lacking in self-pity: “as a child I had the right answers and wanted to give them. And because of this the teachers found a way to put me in my place, to ensure I was humiliated before my peers.” Well, Anthony Powell used to say that self-pity was usually a characteristic of the bestseller, but I doubt if there is enough of a story here for the book to be that.

There is nevertheless much to admire in this short novel: much fine and evocative descriptive writing, many interesting and intelligent observations. So, for instance, writing of her brother, the narrator says: “For a man whose commitment to his own interests was so very serious, it must be, I reflected, no small thing to throw off the yoke of one’s history. He had done very well for himself in that regard.” Henry James would surely have approved of that comment.

And yet, while enjoying and admiring many passages, I find myself repeatedly asking “what is it all about?” and finding no satisfying answer. This may well be due to my own inadequacy. Likewise, the narrative seems weak to me. “What,” Scott once remarked, “is the plot for but to bring in fine things?” – a good question of course. Well, there are fine things in abundance here, for Bernstein is a very gifted and intelligent writer. There are pages anyone might have been proud of writing. Yet I find myself sighing, “where’s the bloody plot?” Where indeed is the story, for a novel can do without a plot, at least without much of one, but it can’t really do without a story – and I never found myself asking “what happens next?”

Study for Obedience, by Sarah Bernstein, Granta, 193pp, £12.99