Book review: Shadows and Light, by Alasdair Soussi

Biography is not a single genre. I have read biographies that are fawning and some that are vituperative, some which are ploddingly academic and some which relish in their own literary flourish. That said, I have never not learned something from reading a biography, whereas there are plenty of novels that I have dragged into the cerebral version of the recycle bin. To qualify that, there are very few biographies I would re-read.

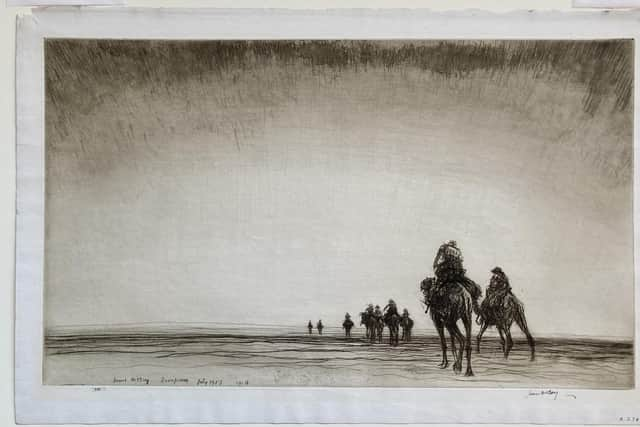

This, the subtitle tells us, is “The Extraordinary Life of James McBey”. McBey was an etcher and painter, born in Aberdeenshire in 1883 and who died in Morocco in 1959. He was, in his lifetime, reckoned the equal to Rembrandt or Whistler in terms of etching (a point made numerous times here), a war artist who captured the likeness of TE Lawrence, an enthusiastic philanderer and a wealthy, famous man. Fame, during life, is often transitory; and despite the plaudits he received he does not have the same status now as MacTaggart or Peploe. The self-portrait on the cover seems to me ill-chosen as he looks like Charles Gray playing Blofeld in Diamonds Are Forever. He also seems preening and self-regarding. A proper assessment of his value as an artist is rather hobbled since the author states at the outset that “this is not a book about art, but rather one in which art features… and prioritises the lesser known aspects of the man himself over any wider discussion of his artistic merit”. To make a case for a biography of an artist without detail on the art is a somewhat curious proposition.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt is also difficult in that if McBey is known at all these days outside of his home area, it is as a diarist and the author of a remarkable autobiography, The Early Life Of James McBey. Biographers who write about autobiographers (and it should be noted that his was published posthumously, latterly in the Canongate Classics series) face a simple set of questions: is the subject telling the truth and what is the subject leaving out?

McBey had an eventful life; whether it can rightly be called “extraordinary” is more problematic. He was illegitimate, although he was always called by his absent father’s name. His mother was remote and vicious and eventually went blind before committing suicide, and he found her hanging body. There is some shop-worn Freud in attributing his promiscuity and adultery to the absence of maternal love and paternal guidance. The other culprit is, of course, the strictures of Calvinism, and Soussi is remarkably silent on why, towards the end of his life, McBey encodes prayers in his diary alongside conquests.

A major problem with this book is the use of the subjunctive voice. On a single page we have “what if he succeeded and spent the rest of his days as a pen pusher?” (he was employed as a bank clerk at the time), then “if McBey caught his reflection on his first walk to the arresting four-columned building”, then “his first impressions of banking must have occupied his thoughts” and he “might have seen” his manager, with his “bushy eyebrows” as a subject who “probably had known little but the daily monotony of officialdom”. The hypothetical runs through the book, and jolts the reader into wondering “Well, did he?” The most egregious example is an account of him at his family’s graves with his new wife: “’Two generations of my family are buried here – seven in all’ McBey might have said to Marguerite as they stood over the Gillespie gravestone in Poveran Kirkyard with the bare autumn trees shivering around them. ‘But how I miss my granny – Mary was the best of us.’” That is imagination and not research, and not to qualify it with the first person – “I like to think”, or “I wonder” – is in bad faith. We don’t know what McBey thought or said or did, so don’t just make it up.

It also highlights another problem, which is a reliance on over-writing and cliché. So we have McBey “wrapped up against the wintry weather in gloves and jacket, as biting winds from the North Sea chilled Aberdeen and its inhabitants to a shiver”. OK, we get it, he’s cold. There is also a preponderance of detail that none bar the expert or obsessive needs to know. McBey travelled on the St Sunniva, which was a “966 grt vessel”, built in 1887, and could go at 15.5 knots. A clutter of minutiae removes the emotional core of the book. One review said, perceptively, “James McBey is one of those few fortunate artists who has not had to wait for acclaim too late to enjoy it”. There is something almost curse-like in those words.

McBey is significant, as an artist, and as a memoirist. There is something to be said for reappraisals of artists like Ravilious, Piper, the extraordinarily depraved Gill, Spencer and suchlike rather than just genuflecting to Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp. But this seems a squandered opportunity. As a fellow critic once acidly said of a famous novelist, “they never found a fact they didn’t like”.

Shadows and Light, by Alasdair Soussi, Scotland Street Press, £29.99. An exhibition of McBey’s work, The Wonderful World of James McBey, is at the Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, until 23 December, https://www.thefineartsociety.com/exhibitions/190-the-wonderful-world-of-james-mcbey-the-fine-art-society-and-fettes-fine-art/