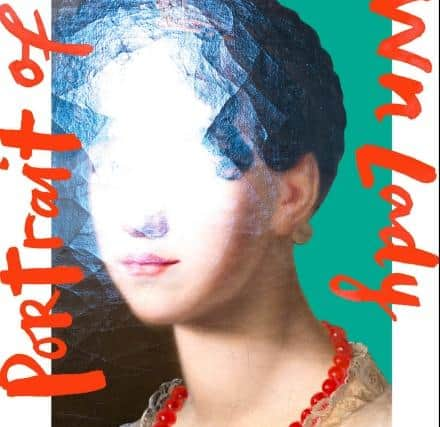

Book review: Portrait Of An Unknown Lady, by María Gainza

This is a truly exquisite novel. Before lauding it, I ought to mention that it is part of a resurrection of Harvill Secker’s famous “leopard” colophon books. A little like checking for hallmarks on silver, it is a design classic that bibliophiles will know. Harvill was founded in 1946 stating “the editors believe that by producing translations of important books they are helping to overcome the barriers, which at present are still big, to close interchange of ideas between people who are divided by frontiers”. I cannot think of a more timely venture. I could not say honestly that I have liked every Harvill book, but they have never failed to interest me. This I can say unabashed is a delight. It is moving, clever and written with a wry precision. I cannot vouch for the translation, being unacquainted with the Spanish original, but Thomas Bunstead’s English is arch and frosty, and I cannot believe that La Luz Negra lacks these qualities. Although, given the novel is about imposture, deceit, sleight of hand and misdirection, I might be completely in error.

Portrait Of An Unknown Lady opens with a woman signing in to a hotel in Buenos Aires under a false name, intending to write a work which is partly an investigation and partly a confession. Having been given a job by her uncle in the valuations department of a bank, she was taken under the wing of the cryptic and aloof Enriqueta Macedo, a specialist in the authentication of art works. She eschews modern technology preferring a highly honed taste, an eye for specific details and particularities. She is given to rather gnomic pronouncements such as “Art… is the cheapest lie detector I know of”.

Advertisement

Hide AdEventually, our unnamed narrator is made a confidante. Enriqueta, as well as giving guarantees on the artworks, has a sideline in giving fake authentications. As a younger woman she had been part of a group of counter-cultural figures staying at (their name) the Hotel Melancholical. One of them, Renée, has a great capacity for imitating paintings and even the style of painters – not forgeries as such, but convincing possibilities. At one point Enriqueta refers to a work as being “very… perfect”, and is welcomed in with “no flies on you”. So it begins. Enriqueta and her associates and protégé are “romantics, rebels to the bourgeoisie and that whole way of seeing the world: the buying way”.

I confess I have a slight penchant for books about art forgery, from William Gaddis’s The Recognitions to Ken Perenyi’s Caveat Emptor to Eric Hebborn’s False Impressions and even the wonderful John Mortimer story, “Rumpole And The Genuine Article”. Enriqueta sums up the problem succinctly: “can a forgery not give as much pleasure as an original? Isn’t there a point where fakes become more authentic than originals? And anyway… isn’t the real scandal the market itself?” Or as her co-conspirator puts it, “I sometimes wonder if art fraud wasn’t the twentieth century’s single greatest piece of art”.

The quest for Renée is ever more elusive and beyond reach. Was she a genius or a hack? Was she a drug addict? Did she slip away to become a horticulturalist specialising in cacti? Did she have a pet crocodile? Did she say “the idea of the normal repels me”, or was she a prostitute? Part of the joy of the book is in this shifting, evasive figure. As our guide writes, “I confess I had come to a point of thinking that she didn’t actually exist, was rather a product of a group flight of fancy, a collective delirium, the dream of an entire generation – perpetuated in countless stories, passed like Chinese whispers down to later generations, morphing all the way”.

But the book is playing a far more intricate game. It seemed plausible to give nods to writers such as Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, given the interest in the aesthetic, the fictitious and the transgressive. When we reach the actual painters – Mariette Lydis, Pedro Figari – I presumed they were fictions as well. Well, no. It was a pleasant morning looking at their work, if sometimes disturbing. Surely another of the characters, Federico Manuel Vogelius, was an invention? No, he did exist (or the conspiracy is far vaster than I assumed). The novel entrenches the guiding principles of Harvill. I had a passing acquaintance with Latin American art (Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Remedios Varo, Lygia Clark) but had never heard of the figures that flit here. I do now.

The book is not just a puzzle-box and a Baedeker, since there is an emotional resonance especially around lives dislocated and compromises made and promises kept. As much as the narrator is haunted, the reader will be haunted. I cannot give away the ending which is not a closure, but it is quite remarkable. It is also funny, especially when we are given a glimpse behind the curtain of being an art critic. “Nobody was to write about art anymore” says one editor; but Gainza has made of that a genuine work of art.

Portrait Of An Unknown Lady, by María Gainza, Harvill Secker, £14.99

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions