Book review: Penguin Classics Science Fiction Series

Between the Era of the Penguin Classics Black Spines (1963, designed by Facetti, sans-serif font) to the Age of the New Black Spines (2003, italic book title, author in russet tones) there were the brief Years of the Flash Top Black Spines. It was a simple colour coding: red for English language, yellow for European (which included Russia and Scandinavia), green for “Oriental” and purple for the Greek and Roman classics.

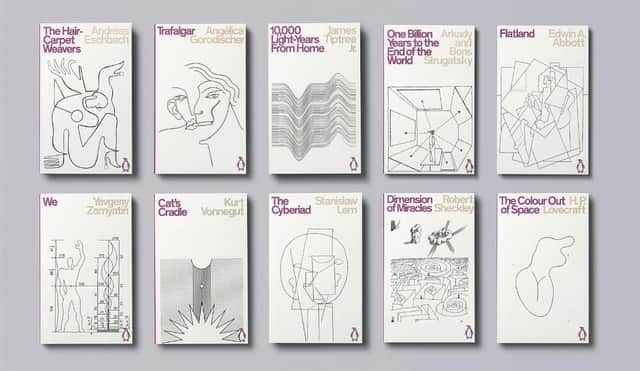

I wonder if the design of these new “Penguin Classics Science Fiction” is a slight nod, as they are handsome books with purple spines. The new Emperor was said to have “taken the purple” – has science fiction now become more important than Sophocles and Cicero? They also have the most beautiful covers: black and white line drawings by Le Corbusier, Hans Arp, Picasso, Saul Steinberg and others. If you expect science fiction to come in polychrome fluorescence, with a vaguely phallic spaceship, then this insists on a different idea; that science-fiction and Modernism always went hand in hand.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe first ten titles are a wonderfully eclectic selection, and prove that science fiction is not a unitary genre. There are collections of short stories, philosophical speculations, horror, satire and that great category, “uncategorisable”. The earliest dates from 1884; Edwin A Abbott’s Flatland, a “romance of many dimensions” and a mathematical primer. Zamyatin’s We (1924) is to my mind a much greater dystopia than either Orwell or Huxley. There is a judicious selection of three HP Lovecraft stories, from 1927, 1930 and 1935, very much in his cosmic terror vein rather than his more racist tone. Although I like Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle (1963), with its freewheeling polemic and apocalyptic concept, I might have preferred either The Sirens Of Titan or the more metafictional Breakfast Of Champions to re-read.

Another familiar name might be Stanislaw Lem, mostly because his novel Solaris has been filmed three times, once by Tarkovsky. It is ingenious to take a less well-known work of his, The Cyberiad (1965), since it showcases his other registers. Two “constructors” – robots or embodied artificial intelligences – called Trurl and Klapaucius, who are friends and rivals, have various adventures and mishaps, almost akin to a Bouvard and Pécuchet, or Vladimir and Estragon, or Laurel and Hardy of Outer Space. Although it is funny, it is serious; not just in the metaphysical speculations but in the sheer unimaginable nature of what they are describing. The word-play and ingenuity in this is laugh-a-page good.

It was clever, too, to include Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s One Billion Years To The End Of The World (1977), a piece of Soviet dark comedy where Dmitri can never make his scientific discovery because of interruptions, secret policemen and jealous colleagues, leading to more and more fanciful interpretations of what is actually going on. The story “Roadside Picnic”, not here, alas, by the brothers also was the inspiration for Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

I hadn’t read Robert Sheckley before, but on the basis of Dimensions Of Miracles (1968), I certainly will. There is an effervescence to this novel, about a hapless Galactic Lottery winner who finds getting home is more difficult than picking up the prize. The comparisons with Douglas Adams are apt, but Sheckley seems to go deeper into the weirdness of what the unknown might be like. Also, it has a comedy dinosaur and my favourite line of any of them: one subcontractor for creation says, of churches, “Why should I go to a place that a God would not enter?”

The others were complete revelations. Trafalgar (1973) by Angélica Gorodischer is interlinked stories, featuring the eponymous anti-hero. Although the stories are told in contemporary Argentina, Trafalgar himself is a gadabout, skipping from planet to planet with nary a care in the world except turning a profit. The disjunction between a clearly evoked reality and multiple alternate worlds is part of the charm, but there is steel here too. A story like “The González Family’s Fight For A Better World” is horrific, with the dead having a literal death-grip on the living. I had read a few stories by James Tiptree Jr, but 10,000 Light-Years From Home (1973) was something of an eye-opener. For a start “James Tiptree Jr” was actually Alice Sheldon, and reading the stories made me wonder why anyone was taken in by the pseudonym. The range here is staggering. One story, “Faithful To Thee, Terra, In Our Fashion” is a bleak satire on Monster Truck derbies. “The Man Doors Said Hello To” is gooseflesh. The stories especially about femininity and bureaucracy (who thought science fiction could do the meaning of logistics management?) are superlative.

Finally, there is Andreas Eschbach’s The Hair-Carpet Weavers (1995). I have never read anything like it. On a distant planet, an indentured but respected class devote their lives to weaving carpets, made from their wives’ hair, to festoon the Emperor’s palace. Rumours abound that the Emperor is actually dead. There are no hair-carpets in the palace, but they were always sent on time. Each chapter had me click “so here’s our hero” and each time I was wrong. The ending is devastating, and as a work about what totalitarianism actually is, it is nonpareil. Science fiction is not genre. It is Literature.

Penguin Classics Science Fiction, £8.99 each

A message from the Editor

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director