Book review: Orwell’s Island, by Les Wilson

Eric Blair’s dislike of Scots and Scotland dated from his years at St Cyprian’s, his prep school in Sussex. There were a number of boys from Scots – or Anglo-Scots – families there. They were the kind of people who headed north in summer for fishing or deer stalking. The headmaster’s snobbish wife adored them and insisted they wore the kilt on Sundays. Young Eric resented this favouritism and consequently Scotland and Scots, though his own name and family were more Scottish than English. Later, serving in the Burma police, he disliked the Scots planters and businessmen he met in the club there. When he came to publish his first book, Down and Out in in Paris and London, he chose a very English pseudonym, George Orwell. George sounded solidly, roast-beef English, though plenty of Scots were called George too, while Orwell is a river in Suffolk where the Blairs lived.

Les Wilson, in the introduction to this elegant and persuasive book, says he is a lifelong admirer of Orwell, but was formerly dismayed by this anti-Scottish prejudice. The more he learned about the months from 1946-8 that Orwell spent in Barnhill, however, the cottage he rented on the Ardlussa estate on the north end of Jura, the happier he has been to find that the experience of Jura gave him a fairer understanding of Scottish life and character. He convincingly shows how his anti-Scottish prejudices withered.

Advertisement

Hide AdThough he was as active working outside on the garden he created as his wretched health permitted, it was life on Jura which gave Orwell the time and distance from London life to write Nineteen Eighty-Four. He wasn’t a recluse there, couldn’t indeed have been lonely, for the house was never empty. His sister and her future husband were there, friends visited and, most of all, there was the presence of his very young adopted son Richard.

Wilson writes of Orwell with admiration, respect and understanding. He was an odd mixture, a rum cove indeed. An Etonian critical of the ruling class and hostile to the British Empire, he wasn’t, despite strenuous and sporadic efforts, a Man of the People. He remained an Etonian eccentric and many of his close friends were fellow Etonians – he put the infant Richard down for Eton, though he wouldn’t in the end go there. He had high literary ambitions but his pre-war novels aren’t really much good (though Wilson has generous words for some of them). It is really only his name which keeps them a bit alive while better writers of the same kind of novels are all but forgotten. There is little humour in them, and Orwell himself was more joked about than joking. Cyril Connolly, his friend from both St Cyprian’s and Eton, once said Eric couldn’t blow his nose without moralising about conditions in handkerchief-making factories.

Coincidently, I have been reading Wilson’s engaging book after Nicolas Shakespeare’s enthralling biography of Ian Fleming. Orwell and Fleming were in the same year at Eton and Fleming was the kind of Anglo-Scot whom Orwell would have disliked then, the ones who travelled north to shoot and fish on their Highland estates, though actually Fleming disliked both sports. The Flemings, unlike the Blairs, were immensely rich, Ian’s grandfather, Robert, born in a Dundee slum, having founded a merchant bank and financed American railroads, businesses and construction. But though Ian never lived in Scotland, he described himself as “Scotch and Presbyterian”. His books were mocked by his wife’s literary friends, but here is the point of resemblance to Orwell: Nineteen Eighty-Four and Fleming’s James Bond have both escaped, indeed transcended, literature to become inescapable elements in the modern world.

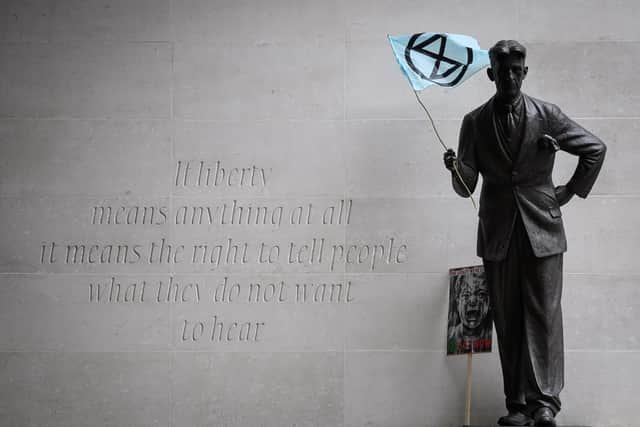

Les Wilson rightly says that Orwell foretold the world we live in, one where there is no need for a Ministry of Truth to establish lies, but where “fake news and hate speech”, along with bots, troll factories and “media ownership by a clique of super-rich” do the Ministry’s work for it. How horribly true; call for Bond.

Orwell’s Island, by Les Wilson, Saraband, £9.99