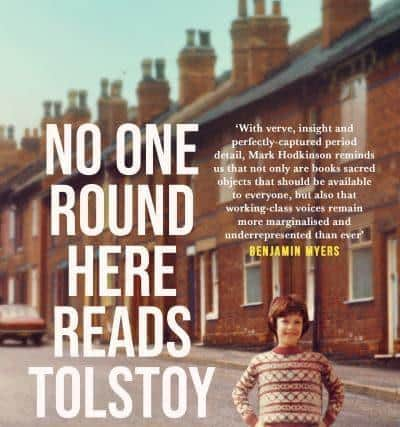

Book review: No One Round Here Reads Tolstoy, by Mark Hodkinson

The problem, I think, with this volume is that it is actually several books between two covers. It is subtitled “Memoirs of a Working-Class Reader”, and in part it is exactly that. The opening sections, however, are interspersed with italic reminiscences of the author’s grandfather, who suffered from some form of mental illness, to the extent that he was subjected to electro-convulsive therapy. The latter part deals with the author becoming a publisher. The different sections never quite gel in terms of tone, unfortunately. The sections about the grandfather – a complex, charming, distressed man, whose throwaway remarks often contain important insights – might easily have been the whole work, not just the sultanas in the scone.

Class is a very complicated subject. By chance I had just finished reading Stuart Jeffries’ Everything, All The Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern. It is a scattergun book, but has pertinent things to say (I can’t imagine another book that segues from the Sex Pistols to Margaret Thatcher as differing iterations of iconoclasm). But on class, and capital, he is good. He uses the scheme that the BBC deployed in its “Great British Class Survey”, itself a nuancing of the work of Pierre Bourdieu, by differentiating between economic, cultural and social capital. Put bluntly, this means distinguishing between what you own or earn, versus your education and whether you go to the football or the opera, versus who you know. Let me say for full transparency that I grew up middle class and would be considered in the upper percentiles for the latter two and woefully inadequate in the former. (Posh but poor, one might say). So in terms of this book, it is useful to think about these varying spectra of what class means. Does becoming a journalist, a published writer and a publisher “class-scrub” you, or can you never wholly escape your roots? I am reminded of Dennis Potter, who spoke RP when back in the New Forest and played up his regional accent at Oxford. Register-switching is an acquired and commendable skill.

Advertisement

Hide AdHodkinson is a self-confessed bibliophile. He is at pains to point out he is not a bibliomaniac, but has acquired some 3,500 volumes. (It’s not a competition, but I thought: huh, amateur). His descriptions of being a lover of books, or rather the qualities that might enhance it, are a checklist I could cross off: short sightedness, infant asthma, few friends, a degree of thrawn-ness, a fascination with Penguin books. Although Mum would say my greed for books started earlier, I blame both the Ladybird series by AJ McGregor and Roger Hargreaves’ Mr Men because they had all the other titles on the back. If I had one, I had to have all. There is some interesting material here about the compulsion to have books, and indeed how it is a form of bulwark against mortality, in that having but not having read means there might be another day. The descriptions of the poverty of the north of England in the 70s and 80s ring true, and have the usual balance between the unconscionable (bullying, sexism, alcoholism) and the queasily quaint. It seems significant that the first author Hodkinson really writes about is James Herriot, and the same tone of plain speaking, nowt so queer as folk sentimentalism seems telling.

By far the best parts of the book involve the experience of reading working class writers; the so-called “Angry Young Men”, though credit is due to Hodkinson for mentioning the female writers such as Shelagh Delany and Monica Dickens who were also trying to chronicle and explain what life was really like for many people. That said, there is a paradox in this account. Although he asserts that he wasn’t looking for books which reflected his environment, he insists on the importance of writers like Barry Hines, Alan Sillitoe and John Osborne. He was also swept up in punk and post-punk music (there is a degree of veneration for what my friend Peter calls “The Morrisiah” and The Smiths).

Latter parts of the book have a tetchy, almost peevish tone. Take this for example: an agent has told him there is no “divine right” to be published. “I said nothing at the time because I was afraid to appear conceited, which I’m not any more. I wanted to say that, actually, a passionate love of books, a commitment to them allied to a natural and cultivated talent qualified, as near as damn it, to a divine right”, although there are “lots of mediocrities out there and plenty of well-connected opportunists”. The material about publishing will interest people interested in publishing. The polemic around libraries – that they “have tried to offer too much to too many” and ought to be “an umbrella to the world, keeping out the noisy, the ill-mannered, the non-book people” made me wince. It goes back to the question of how we determine class: what right has Hodkinson to spy out “non-book people?”

This is a book in praise of reading. It is, regardless of background, a universal right. I don’t care if you are reading Dan Brown or Fyodor Dostoyevsky, though I can still have my own preferences, such as knowing that Morrissey quoting “eyeless in Gaza” might refer to Aldous Huxley’s novel, but it in turn is a quote from Milton’s Samson Agonistes. Always useful to know more, I've found.

No One Round Here Reads Tolstoy, by Mark Hodkinson, Canongate, £16.99

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions