Book review: My Father's Letters - Correspondence from the Soviet Gulag, translated by Georgia Thomson

As the USSR and the Soviet Union Communist Party began to disintegrate in the late 1980s, Memorial was formed – a group of anti-totalitarian Russians and Ukrainians determined to promote the truth about the Soviet past and to perpetuate the memory of the Gulag victims. Now, Memorial gives legal and financial help to many of these victims along with researching and publishing information about those sent to the camps or shot.

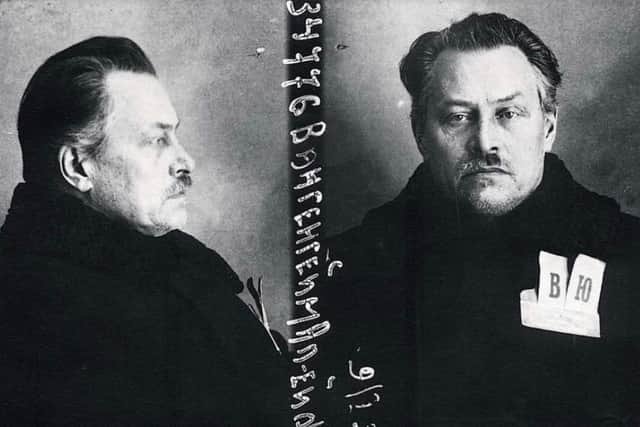

The archivists who prepared this collection of letters and memories of 16 victims chose fathers rather than mothers because although there are many letters from women in the archives, the women were more likely to survive and the focus here is on what in several cases turned out to be the final communications between fathers and their children. Astoundingly, these stories are not miserable. Yes, the men mention their inadequate shelter, clothing and food, but the overwhelming impact is the expression of their love for their families.

Advertisement

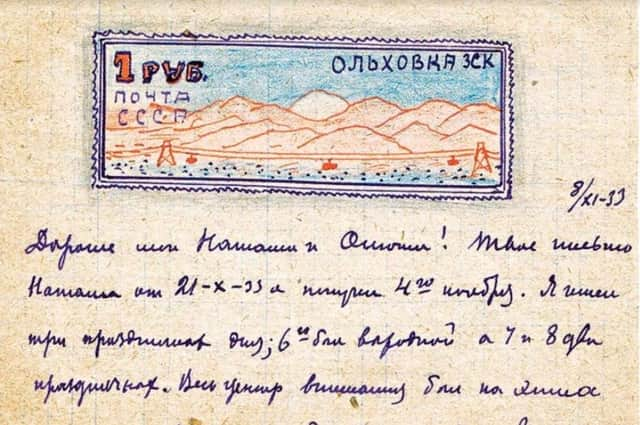

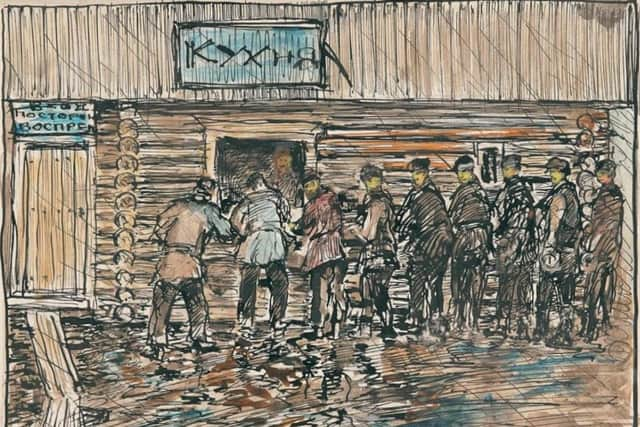

Hide AdThey illustrated their letters with drawings, cartoons or beautiful pieces of art sometimes created only from scraps. Some had office jobs and could obtain paper to make small books for their children. In their letters all of them stressed to their children the importance of education and the need to pursue learning. One man sewed a letter to his wife, daughter and son, with a fishbone needle into a fragment of bed linen and had it smuggled out of prison by a released cellmate who hid it inside his shirt collar.

My Father’s Letters is beautifully produced, with photographs of the men and their families, colour reproductions of the original correspondence and appendices giving details of individual prison camps, Soviet Judicial Bodies and Secret Police Agencies. There is also a section outlining Memorial’s mission. Georgia Thomson’s superb translation is supported by useful footnotes, with information about writers, places, politicians, Russian language and culture.

Apart from one father, an unashamed and vocal Trotskyist from the peasantry, the men are doctors, teachers or managers and if not committed to the regime at least they are good citizens, despite resenting the injustices dealt them and appealing against their arrests and punishment. They often assure their families that their arrests are the result of mistakes, but Memorial’s research into secret police and legal documents shows how these innocent men have been targeted: cases include a chance remark to a friend, drafting a complaint against being passed over for a promotion at work and another, president of the All-Russian Society of Stamp Collectors, whose lists of stamp catalogue numbers were assumed to be encrypted messages for foreign spies.

Alongside the analyses of these appalling injustices are examples of the power of family love that the Soviets were trying to extinguish. One son says, ‘‘I walked up to the train carriage to give Father a teapot and some food for the journey. He deliberately let the teapot fall so that I would pick it up and he could squeeze my hand.’’ One of the letter writers to survive arrived at his daughter’s workplace in 1946, grey haired, ill and stooping. It was only when he spoke that she recognised him. He had journeyed for many days and despite his hunger had carried with him a half-litre jar of red caviar “for Mama. She always so loved red caviar and it is difficult to get hold of these days.”

Another said, "Do you know what saved me? Letters. The connection with home.”

The importance of the work Memorial does is clear in what what one returnee said to his teenage daughter in 1946: “there will be a time when it will no longer be those in prison or in exile who are shamed, but those who allowed this to happen. We will be considered heroes…This will happen in your lifetime.”

Advertisement

Hide AdMy Father’s Letters – Correspondence from the Soviet Gulag, translated from the Russian by Georgia Thomson, Granta, 300pp, £30

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions