Book review: The Murderous History Of Bible Translations by Harry Freedman

The Murderous History Of Bible Translations by Harry Freedman | Bloomsbury, £20

‘So liek teh Ceiling Kitteh lieks teh ppl lots and sez ‘Oh hai I givez u me only kitteh and ifs u beleeve him u wont evr diez no moar, kthxbai!’”. For the uninitiated, that is John 3:16 “translated” into LOLcat – unbelievably over three-fifths of the Bible can now be read in this asinine form. It doesn’t get into Harry Freedman’s brisk and intelligent guide to the frequently violent circumstances surrounding Biblical translation, though I would certainly consider at least a Chinese burn to those murdering the English language in this way.

Advertisement

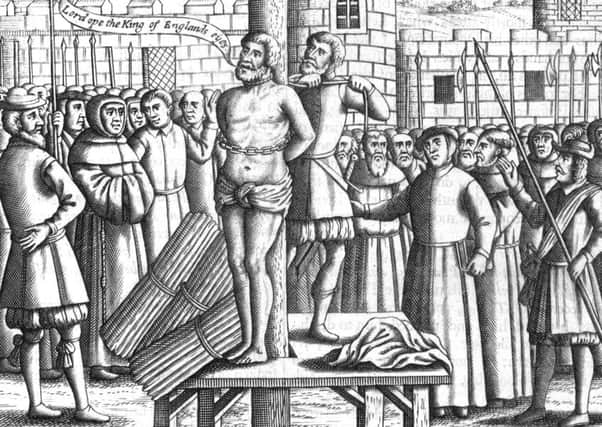

Hide AdIndeed, the “murderous” part of the title here is by far the least interesting, and one suspects a degree of “sexing up” given how careful and judicious much of the book actually is. The execution of William Tyndale is the most obvious intersection of translating and killing, and Freedland draws in, sometimes tangentially, events such as the suppression of the Cathars, the martyrdom of Jan Hus and the Münster Revolt. Often these involve the interpretation of a translation rather than a translation itself: a persistent concern is the anxiety of authorities over vernacular Bible reading, and the potential for readers to come to their own conclusion about verses like “to the pure all things are pure” or “neither said any of them that ought of the things which possessed was his own; but they had all things common” or “I came not to send peace, but a sword”. One very interesting aside involves the Spanish Inquisition, who suspected converted Jews of using translations of the Old Testament to continue practising Judaism. It led to mass-burnings of the Bible – “a mountain of books” according to one Jesuit – a fact nobody seems to have thought ironic.

The earliest sections prove the most fascinating. Freedman, who has written an excellent book on the Talmud, doesn’t just cover the most famous translations: the Septuagint, a Hebrew-Greek version of the Old Testament produced for the Library of Alexandria (and, according to Philo, by sequestered scholars who miraculously came up with identical versions); Origen’s Hexapla, which concurrently featured the Hebrew, Hebrew written in Greek characters, the Septuagint and three translations by Aquila, Symmachus and Theodotion; Jerome’s Vulgate, first Greek to Latin and then Hebrew to Latin. He also delves into more esoteric versions, such as the Targum, a version in vernacular Aramaic when Hebrew had become a preserve of the elite, the Syriac Peshitta and the early Arabic translations by the Jewish Saadia ben Yosef and the Muslim Hunayn ibn Ishaq.

More perhaps could have been done with the varying canons of the Bible. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church includes the Didascalia; the Armenian Bible has a third epistle to the Corinthians; parts of the Coptic Church also use I and II Clement. What all this shows – and what cannot be repeated often enough – is that the fundamentalists and literalists came to the game very late indeed. There is also in the early sections a quiet optimism about what biblical translation can achieve. Evangelism played a significant role in preserving, and in some cases creating, languages. The Goths had no written script before Ulfilas (whose name means Little Wolf) started his translation. Mesrop Mashtots tried at first to teach Armenians using Aramaic script – and set up a nationwide literacy programme in the fifth century CE – but realised it couldn’t convey the sounds of Armenian properly: thus the Armenian alphabet was born. Saints Cyril and Methodius created the Glagolitic script, from which Modern Cyrillic evolved.

The chapters on the King James Version, the Catholic Rheims-Douay and the Geneva Bible show how translation is always ideological. It also highlights how human frailty intervenes at every turn: the first edition of the King James has 351 printing errors. (One in the eye for fogeys as well). The action then turns primarily to America, where the most intriguing is John Eliot’s Bible in Algonquian. Having to invent terms for concepts they did not have meant that the Algonquian Indians rarely understood it.

The Bible still raises tempers; as Pastor Luther Hux burning a Revised Standard Version or the outcry over gender neutral Bibles amply shows. The latter sections are markedly and regrettably more Anglophone. It was only after the defeat of the Jacobites at Culloden that James Stuart and Dugald Buchanan started on a Bible in Scots Gaelic (translation often comes on the heels of subjugation).

Early Chinese translations were only allowed “into erudite language proper to the literati”; when vernacular versions did appear they had a significant role in the Taiping Rebellion of Hong Xiuquan, who thought he was Jesus’s younger brother.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne significant translation doesn’t exist. Although some of the Psalms were translated into metrical Scots, a Bible in Scots was not a priority for John Knox and other Reformers. One wonders how different the standing of Scots would be now had there been an equivalent of the King James version north of the Border.