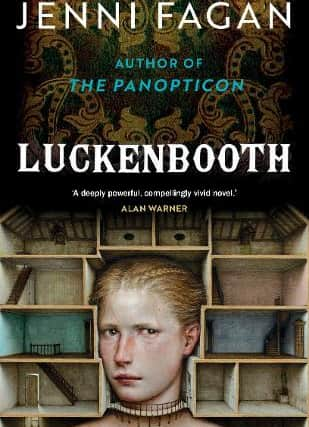

Book review: Luckenbooth, by Jenni Fagan

Appositely, Jenni Fagan’s third novel has an epigraph from Hugh MacDiarmid: “Edinburgh is a mad god’s dream.” Perhaps the most important point of relevance for this deftly structured and white-hot furious novel is something overlooked; that MacDiarmid, that arch-againster, refused to use the capital “G.” It is a whirlwind of a novel, and I am certain that various labels will be attached to it – Caledonian magic realism, tartan gothic, something nasty in the shortbread tin, Angela Carter in a kilt cross-hatched with safety pins. What it is, is radical and profoundly fabulist. It is about the stories we are told and whether there is the possibility of there being new stories.

Given how diverse and extravagant her subjects are, Fagan has chosen to tether the novel (is it a novel? Or a series of interlinked short stories?) to one particular building, No. 10, Luckenbooth Close, a nine-story tenement just off the Royal Mile. The narrative ranges from 1910 to 1999, hop-scotch fashion, across the building. Each of the three sections has three principal characters, each of whom has three chapters, and the novel migrates from the first floor to the ninth, although, as any reader of weird fiction would realise, the solution to the vampiric nature of the building does not lie in any of the obvious landings. The dwelling is cursed, a damage magnet, and draws to itself sufficient psychic damage to sustain it until an exorcism or apology can be wrangled out. This allows for a very intriguing cross-section of 20th century, subterranean Scottish social history.

Advertisement

Hide AdSo, to scroll through the denizens and passers-through, we have initially Jessie, a girl from an unspecified island whose father might be the devil, who has the beginnings of horns and who has been sold as a surrogate to bear a child to No. 10’s owner, the philanthropist and hypocrite Mr Udnam. Readers might be well advised to ensure that their “willing suspension of disbelief” is fully functional before embarking further. Fagan bravely does not allow the get-out clause of the supernatural elements being metaphors incarnate or symbols made real. There really is something of the dark at work here.

The second part of the first triptych introduces Flora, in the aftermath of the Great War, whose lover dismisses those who call her “freak, hermaphrodite, boy-girl, in-between” and who “was the first one to tell her that she was not two things but one perfect thing made from stardust.” Then we get Levi (not his given name) and African-American working on bones in the Royal Dick Vet School who is using the spare parts to build a mermaid. He gets the novel’s moral core: “all I want to do is think. It is a transgressive act.” The later chapters feature a woman training to work behind Nazi lines, a medium who genuinely can summon spirits, the writer William Burroughs, the female leader of a criminal gang calling themselves The Original Founders, who run strip-bars in the “Pubic Triangle,” a miner who is afraid of daylight and eventually a lost soul trapped on Hogmanay in the teetering edifice of No. 10. Readers familiar with Edinburgh will relish the number of shards of myth, urban legend and obscurity she braids through it (I laughed aloud when the penguin parade turned up).

There is a great deal of imagination and empathy at work here. The structure of the building acts as a kind of framework to contain the pent-up furies, the sense that “there’s nae rights for most humans. There’s only rights for the rich” and that “we are all at the mercy of and malleable to the programmes that raised us – whether they be religious, or class-based, or gender biased. All structures are implemented through an underlying violence and brutality particular to this planet.” Certain leitmotifs bind the disparate narratives across time, and certain burning concerns and legitimate grievances occur with a metronomic precision. The novel poses but does not answer a question about the polymorphous perverse that shadows most of the stories. Is queerness, otherness, a kind of true baseline repressed by orthodoxy and hierarchy, or is it more powerful as a deliberate sabotage of those systems of thought?

There is an argument to be made that there are times and points at which the novel, in general, has to stop being subtle (or worse, knowing) and nail its colours to the mast. Mostly Fagan leaves enough room for ambiguity even if a soap-box is sometimes perilously and tantalisingly close. That there is a streak of sardonic humour throughout helps; as does a relish in language itself, with lists of phobias, zoological taxonomies, Chinese, street jargon and other idiolects all intermingling without diffusing.

On underlying misogyny Fagan is especially perceptive, although there is a slight problem here. The work is clear about the reality of evil (and it not really having much to do with horns or cloven hooves), but less certain about the theodicy; the why of evil. Udnam is monstrous, but he remains a work of motiveless malignity, a black king on a chess-board with no white. Luckenbooth is a daring book, and beautifully written, but understanding the problem and suggesting an answer are different things. “Ideology” may be the enemy, but how does one understand other ideologies or change one’s own? It brings me back to MacDiarmid, as the first word of the line of the poem that stands as epigraph is omitted. The complete line reads: “But Edinburgh is a mad god’s dream.” More space for the but.

Luckenbooth, by Jenni Fagan, William Heinemann, £16.99

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director