Book review: Look For Me And I’ll Be Gone, by John Edgar Wideman

“Stories” it says on the front cover, below the title and above the author’s name, and, yes, there are stories here, many of them encased in other stories, rambling, discursive, disjointed stories, not the kind you might read for agreeable relaxation over a glass by the fireside. Sometimes, often indeed, the story gets lost, buried, and not only because the style is erratic, broken-backed, uncomfortable as the author’s central inescapable theme; the experience of people of colour in the USA and especially in what passes for the American Justice System.

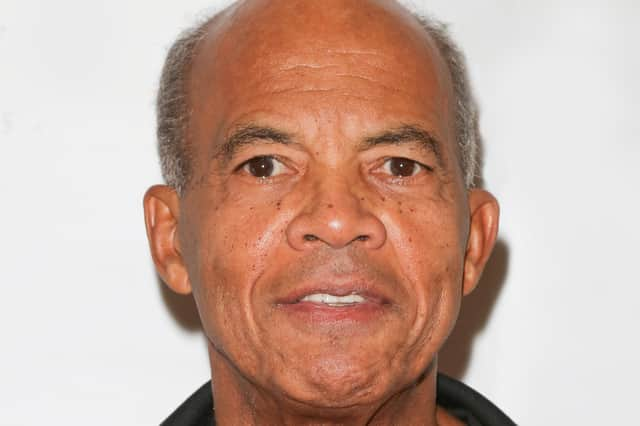

Wideman, now 80, has had a brother and son both doing time, serving grotesquely long sentences, the son for a crime committed when he was a minor. In contrast, he has made his own life a success, a professor and prize-winning novelist, who now divides his time – time again – between homes in New York and France.

Advertisement

Hide AdSlavery, more than 150 years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, is the ineradicable crime at the heart of American experience and especially African American experience, even today; at the heart too of Wideman’s work, just as it was of America’s greatest and still most troubling novelist, William Faulkner. So, Wideman writes, in the story or reflection entitled “Penn Station”, where he goes to meet his brother, released after more than 40 years, “my brother [had been] a danger to himself and to others because he understood deeply that society applied its rules and dispensed its rewards perversely to people of color.”

There is variety here, however. Wideman is rich in ideas, his mind so lively and well stocked that he goes off at tangents, engagingly if sometimes also perplexing to the reader who is not willing or prepared to follow him into the maze he explores. So, for instance, an account of the African experiences of a 19th century Presbyterian missionary who came to be called “the Black Livingstone” leads to a consideration of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and a sympethetic defence of that novella against the sharp criticism offered by the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who called Conrad “a thoroughgoing racist.”

There are so many stories tumbling in Wideman’s imagination that he is often led down an a surprising and twisting path. Well, why not? As he writes, “I’m old. Why pretend I can guess how younger generations of readers will react to my writing?” Why, indeed, one may say; lucky to have them anyway. He continues: “Why care? Hemingway claimed that details are what render fiction convincing. I respect the details of a story. I resist abstractions, generalizations, melodrama, soap opera, O Henry surprises, Joycean epiphanies. If I remember facts, I narrate them as accurately as I am able.” You shouldn’t say a man who has been knocked down was “swimming in a pool of his own blood “ because “swimming would require copious, copious gallons of spilled blood.” Or, of course, simply because it’s a dead metaphor.

A reviewer in the New York Times has praised Wideman’s “willingness to test the boundaries of the short story form.” Well, I’m not sure that there are any such boundaries to be tested. Here stories drift into biographical or autobiographical memories and reflections. Sometimes the narrative, thin even at the beginning, may lead you into a dark forest and leave you to follow a path out of it without much guidance from the author. Like Faulkner again he demands much of the reader: patience and co-operation. There are, one must admit, boring passages here and other incoherent – or at least some way short of coherent – ones. But there is always a probing intelligence, an understanding of the darkness of those compelled by inheritance or circumstances to struggle, and indignation directed at the cruelty and inequity of American justice. It’s a book that demands and deserves attention. Language, Wideman asserts warningly, is “incorrigibly nontranslatable.” Nevertheless we have to keep trying to listen to others and, by listening, hope to find understanding and sympathy.

Look For Me And I’ll Be Gone, by John Edgar Wideman, Canongate, 318pp, £16.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions