Book review: The Living Sea of Waking Dreams, by Richard Flanagan

Richard Flanagan won the Booker Prize in 2014. His new novel, described by the publisher as “a wild and urgent story about family, love and hope set against global catastrophe and climate crisis” has already met with “rave reviews” in his native Australia. It’s certainly ambitious, powerful in its descriptions of drought, bush fires, impending environmental disaster; to this extent certainly a novel for our troubled times. It is also an uneasy hybrid, the private and public themes crudely yoked together, the private domestic part of the novel disfigured by tiresome and rather pointless dashes of magic realism.

Francie is in the intensive care unit of the hospital in Hobart. Her condition is deteriorating. When her daughter Anna, an architect, is alerted by her brother Tommy, an unsuccessful painter who has been caring for their mother, she finds her “unconscious, almost unrecognizable, one side of her face drooping.” Tommy, a failure but a realist, comes to accept the situation. Their mother, a Catholic, should receive the last rites and be allowed to die. His younger brother, Terzo, a high-flier in financial services, insists on doing all that can be done to keep the old woman alive. Anna agrees.

Advertisement

Hide AdAll this is good, credible fiction. It remains credible even when France sees strange things – magical things? – through the window in her hospital room. The family, we learn, has long been dysfunctional. France’s husband developed dementia in his early fifties. One son, Ronnie, hanged himself after being abused by a priest. Anna’s son Gus is mentally disturbed and steals from his mother. Tommy’s son is bipolar. Tommy himself developed a stutter after Ronnie’s death.

Credibility collapses when the magic realism moves in. Anna finds bits falling off her body: first a finger, then a knee. Nobody notices or pays attention. Later bits will fall off her lover Meg. No doubt this reflects or is intended to reflect both Francie’s deterioration and the climate crisis. But since, unlike them, it seems incredible and silly, it weakens the novel. It’s mere fantasy and realism is almost always more interesting than whimsy of this sort.

It’s a pity because other parts of the novel are very good. The relationship between Tommy, Anna and Terzo is well done. The pressure Terzo and Anna put on the doctors to try yet another procedure which may prolong their mother’s life is a convincing example of how wealth and privilege can be used to corrupt professional judgement, and Tommy’s inability for a long time to resist, even though he believes resistance is wrong, is understandable and moving. Indeed all the hospital stuff is good.

So is the evocation of Australia’s damaged, degraded , disappearing and corrupted natural world and the public response to it. Flanagan’s is a persuasive dystopia. Tasmania, Tommy thinks, “was where you came to get away from all that shit, but now it was even here, ancient forests vanishing, beaches covered in crap, wild birds vomiting supermarket shopping bags, a world disappearing, some terrible violence returning for a final reckoning…”

There is much to enjoy and admire in this novel. At his best Flanagan writes with a startling brilliance. As I say, Australian reviewers have hailed it as “a revelation and a triumph... At once timely and timeless.” One reviewer concludes that most impressively Flanagan’s novel “doesn’t end in condemnation. It keeps searching for the proper form for love.”

Well, perhaps. We all read novels differently. It is only fair that a reviewer who is less than pleased or satisfied by a novel should acknowledge that others may find it marvelous. I think there’s a good and very interesting and sympathetic domestic novel of family life and tension, addressing a painful question about the morality of prolonging life, but that this comes close to being suffocated by fanciful invention. The climate crisis makes for a compelling backdrop; nevertheless it too distracts from what seems the essential theme of the novel; how this divided family confronts the reality of approaching death; and whimsy about fingers and knees falling off a woman’s body is silly and irritating, out of key with the realistic element of the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Living Sea of Waking Dreams, by Richard Flanagan, Chatto & Windus, 282pp, £16.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

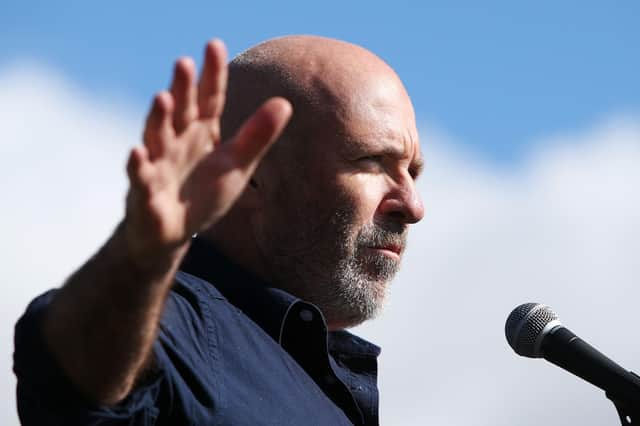

Joy Yates, Editorial Director