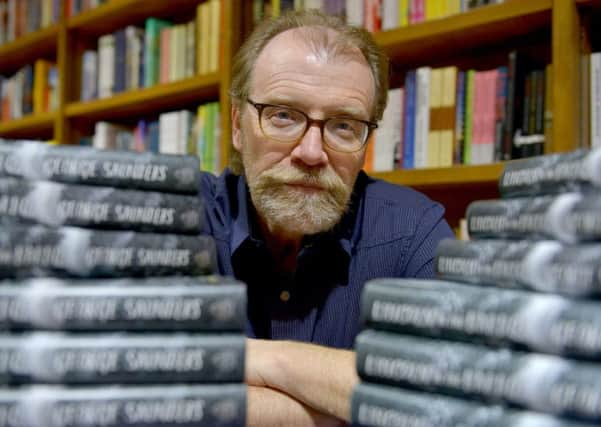

Book review: Lincoln In The Bardo, by George Saunders

The undefined “Bardo” of the title is a kind of Limbo, where souls transition from reality to eternity, and where some of them linger, afraid or unwilling to leave behind the past. It is where young Willie Lincoln, son of honest Abe, finds himself, having succumbed to illness at the age of 11. The night after the funeral, his father, President of the United States and as concerned with his personal loss as with the political tragedy unfolding around him, comes secretly to visit the grave. Or the “sick box” as the ghosts around him call it.

It is a polyphony of a novel, where extracts from books about Lincoln are quoted to forward the narrative and the ghosts are always given the dignity of a citation to their utterances. It is a kind of stichomythia, with two voices especially – a gay man who committed suicide and a middle-aged printer knocked on the noggin – acting as our Vladimir and Estragon in this purgatorial place. They are advised, berated, deceived and blessed by a dead priest, who knows more about the hereafter than he is telling. As Willie Lincoln persists in his – well – supernatural persistence, the ghosts manage to stiffen the nerves and soften the horrors for Lincoln, as he sits cradling his dead child. One thing the gone all want to do – drunkards and spinsters, racists and slaves, idiots and idealists – is to have their story heard.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne idea unites the encomiums: “As though you are reading fiction for the first time”, “arresting brilliance and originality”, “an original – but everyone knows that”, “a true original”. Well, no. The idea of a child in a cemetery assisted by a kind of fauna of wraiths – as well as the obvious ghosts, we have angels announcing “you are a wave that has crashed upon the shore”, the enveloping unrepentant, the bachelors who don’t care they are dead and give the novel its finest line, “and there came down upon us a rain of hats” – is basically Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book. The notion of trying to rescind the afterlife itself because of the Civil War, with real historical figures melding with fictional creations, is the basis of Chris Adrian’s Gob’s Grief. While Adrian has an eschatological horror and awe to his work, Saunders’ version of the afterlife is rather recognisable. There are “diamond doors”, scales, a question – “how did you live?” – and either “a tent of purest white silk (although to describe it thus is to defame it – this was no earthly silk but a higher, more perfect variety of which our silk is a laughable imitation)”, or a place of “spoiled blood”, flaying and sulphur-coloured robes. It might be argued that this vision is nuanced to the particular character, but it is nonetheless pretty derivative. Some of the very old dead are even losing their language, which allows Saunders some Finnegans Wake-esque flourishes, and some gaps in sentences that seem familiar to anyone who has read Ali Smith’s Hotel World.

What Saunders does excel at is sentimentality, and I do not mean that as a criticism. Done well – such as with Hardy’s Jude The Obscure and Little Father Time’s suicide note (“because we were too menny”) – it can be sublime. It is here. Although the reader can feel their heart-strings being tugged, tugged they are nonetheless. It is not just that a novel about a grieving father and a dead son waiting to hear his last words isn’t inherently catch-in-the-throat stuff, it is also politically sentimental. At one point the ghosts swarm into Lincoln’s body. More than the representative of the people and their will, he literally becomes a walking version of Hobbes’ Leviathan, the encapsulation and incarnation of all. No doubt in the days of President Trump, such a fiction has consolatory appeal. But even this seems awkwardly cribbed from a novel like Robert Coover’s The Public Burning, where Richard Nixon is “possessed” by Uncle Sam, to continue his fight against “The Phantom” of Communism.

Saunders is the old-fashioned avant-garde. This is the acceptable radicalism. I would be disappointed in any reader who failed to enjoy it, and equally annoyed if any reader thinks this is the best we can do – or the most pressing response to a changing world.

*Lincoln In The Bardo, by George Saunders, Bloomsbury, £18.99