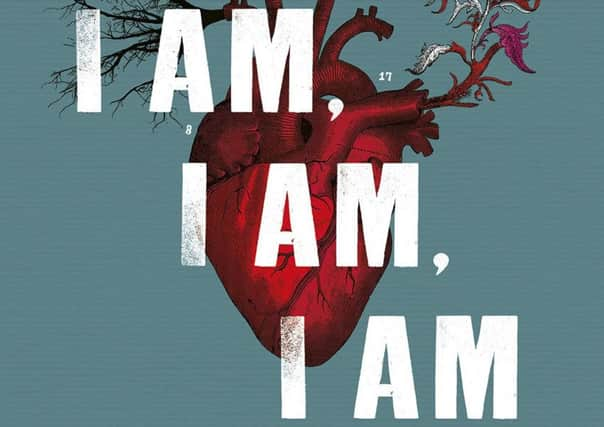

Book review: I Am, I Am, I Am, by Maggie O'Farrell

This is Maggie O’Farrell’s first non-fiction book, following on from seven novels of quiet radicalism. In its own way, it is equally, cautiously innovative. It is billed as a memoir, but its subtitle is more accurate: “Seventeen brushes with death”. Rather than narrate her life, she offers a series of startling vignettes of when her life was imperilled. I will gladly admit that at least one of them – Chapter Seven, “Baby and Bloodstream” – I could barely read for tears.

The book darts around with chronology, opening in 1990, when, as a teenage hotel cleaner, O’Farrell used her day off to go hiking. Something awful happened, involving a predator trying to strangle her with the straps of his binoculars. What is more terrifying is the bureaucratic apathy towards the event and the eventual realisation that this was a “dry run” for a more ghastly occurrence. But it is also a strangely moving exercise in sympathy. As the narrative of this first / not first fearful moment is being told, we also have the strange and eerie watchfulness that will characterise her novels. She writes: “The couple from London, who seem wonderfully, enviably perfect – they hold manicured hands over dinner, they take laughing walks at dusk, they show me photos of their wedding – have a room steeped in sadness, in hope, in grief. Ovulation kits clutter their bathroom shelves. Fertility drugs are stacked on their nightstands. These I don’t touch, as if to impart the message, I didn’t see this, I am not aware, I know nothing”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs much as death haunts her – the reckless childhood dive, the plane in freefall – she haunts death. At a music festival she volunteers to be the target for a knife-thrower; she will swim with abandon in treacherous seas. These brushes with death are both chosen and uninvited. The book is cunningly structured – the quotation above sets up her own, plangently written, account of miscarriage several chapters later. It is exceptionally moving that the most fearful brush with death sometimes does not concern one’s own mortality.

In his Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein used pain as a way of understanding solipsism. I can never know what your pain feels like. While this is true on a cerebral level, one of the real achievements of O’Farrell’s book is to point out that the aesthetic can do what the intellectual can’t. It can convey what pain is. She writes, “I woke up early and the world looked different. The colours of the rug, the curtains, the lampshade were more vibrant: they were pulsing, like a heart, like a sea anemone”. There is a vivid, visceral voice in her attempts to say what pain is. The words here are precise – there are windows cantilevering, the toasted-resin smell of cinnamon bark.

Even more precise are the gradations of tone. O’Farrell moves between I, you and she as if distanced from herself the whole time. The book is structured somatically – Neck, Lungs, Neck (again), Intestines, Cranium, Cause Unknown and so forth. It grounds the book in the real, the sheath of skin we live inside. The interplay between the specifics of the body and the vagueness of the shifting self are beautifully done.

The final chapter is one of the boldest and most terrifying things I have read this year: O’Farrell, discussing her daughter’s illnesses, becomes a kind of character from Greek tragedy, facing down death, baring her teeth at the unfairness of suffering. This is a quite remarkable book, and a lesson in empathy we sorely, yes, sorely, need at this time. ■