Book review: Hollow, by B Catling

In 2002, the novelist M John Harrison christened a genre “The New Weird” in an introduction to a novella by China Miéville. In a provocative subsequent forum post he posed a series of questions. “The New Weird. Who does it? What is it? Is it even anything? Is it even New?” Miéville called it “a moment, a suggestion, a tease, an attitude, above all an argument.” But the term had sufficient traction that by 2008, another fine author, Jeff VanderMeer, could curate an anthology, The New Weird.

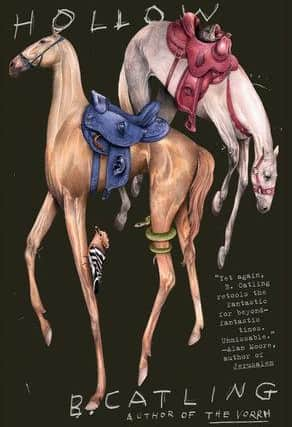

Well, there’s New Weird writing and then there’s Downright Weird. I have been very interested in the work of Brian Catling for a long time, ever since reading his work in the anthology by Iain Sinclair, Conductors Of Chaos. He is the author of the most magnificently bonkers trilogy of novels thus far into our fairly bonkers century, comprising The Vorrh, The Erstwhile and The Cloven. These books examine ecology, technology, theology, colonialism, grief and love, but also have Bakelite robots, a cyclops and a man who has a bow made from his partner’s skeleton. He has also written a novel, Earwig, which features a girl with teeth made of ice and a strange parable, Munky, about ye olde English pubs and the persistence of ghosts. Now we have Hollow which is a sheer, shuddering delight.

Advertisement

Hide AdHollow deploys an archetypal structure that stretches from Seven Against Thebes by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus through to Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven. Or perhaps even The A-Team. Hollow is set during the Wars of Religion in the 16th century, and features a ragtag group of mercenaries tasked with a significant mission. They are to take the new Oracle to the Monastery of the Eastern Gate, at Das Kagel, which some believe is the ruins of the Tower of Babel.

Heading up the quest is the wonderfully named Barry Follett. He recruits his old sidekick, a swashbuckler, a man with “the concealed ferocity of a badger entwined with a righteous determination,” an Irish renegade on the run, a whippersnapper and a pair of brothers who are almost like twins despite the difference in their ages. So that is your Seven, except there’s an eighth, a man called Scriven who is hanged on the first page for “the crime of writing.” But there’s the other eighth, the Oracle itself, which proclaims in the first line “Saint Christopher is a dog-headed man.” The prophecy turns out to be true. What is the Oracle? It is “an abnormality,” limbless with a sing-song voice, that requires sustenance through a truly ghastly form of nutrition and regular confessionals from the band of bandits. It also has an eerie capacity for ventriloquism. Part of the novel’s pleasure is the foreknowledge that they will be picked off one by one, but how and by whom?

At the same time, the destination of this Oracle is in disarray. One monk has been struck dumb, and there is something fishy about the Abbot. Their previous Oracle, Quite Testiyont, is no more, and the anchorite must be replaced since it acts as a kind of lock to an elsewhere. The local villages, and the monastery itself, are being plagued by “Woebegots” and “Filthlings.” When I was reading Hollow, my brain had a little nudge. The descriptions of these creatures seemed familiar and it clicked. They were all descriptions of things in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. Somehow art is bleeding into reality, perhaps because the lock has been broken. Catling is a significant artist as well as a fine writer, and the fusion here works exceptionally.

The whole novel is not just fun, but very clever fun. The incidents along the way are both frightening and hilarious, and the different confessions of the mercenaries means the novel has short stories embedded within it. A woman is inspired to radical action by the secrecy of the religious authorities. The scenes in the monastery are almost as if Guillermo del Toro had been asked to film Umberto Eco’s The Name Of The Rose – and the book does include various scenes where books are especially important. But it is also heartfelt. The idea of the confessions allows for us to see the humans behind the hired rogues.

The novel is a form of phantasmagoria, with church, mission and hostelry equally full of brawling. The use of the Bosch creations makes the diligent reader return to the paintings – a sort of “Where’s Wally?” of those surreal works. For a visual artist, it seems ironic to an extent that in prose, he almost deliberately avoids letting the reader fully visualise. Things remain ambiguous and smudged, which is a form of graciousness: let the reader imagine.

Catling is a rare kind of writer. His work has consistent themes but boundless imagination. It is a certain gift to write the most absurd, horrible, fearful things in a very limpid prose. The literary theorist Bahktin has an idea about “the carnivaleque,” a place where all orders and hierarchies become disrupted. This novel exemplifies that idea.

Hollow, by B Catling, Coronet, £17.99

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions