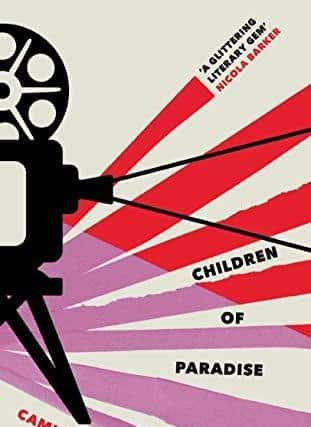

Book review: Children of Paradise, by Camilla Grudova

I am not sure if it entirely the done thing to confess this, but I have a weakness for book endorsements. So when a novel is flagged up with jacket quotes from Nicola Barker, Deborah Levy and Sinead Gleeson, three writers whom I admire a very great deal, then I am more inclined to think it might be worthy of attention, even if I disagree with their opinion. On this occasion, I don’t. Camilla Grudova’s Children Of Paradise is a remarkable and memorable achievement. To combine the gothic, the carnivalesque, the ghastly and the sublime in a relatively slender novel shows considerable talent indeed.

The premise is relatively simple. Holly – not her real name, a young person in a new city and a new country and without employment – sees a sign reading “We’re Hiring” on the door of a cinema. “The Paradise cinema had a gaudy interior and a pervasive smell of sweet popcorn and mildew” we learn in the opening sentence. Its single screen has plaster mouldings of “couples kissing, perhaps not quite human, with long pointed ears and horns, and stars like unrecognisable constellations in the ceiling.” It also has a trapdoor into a functioning sewer beneath them. The astute reader, given the presence of this Stygian river, the distant stars – not to mention the name of the cinema – might expect there to be a strong element of the allegorical to all this.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere both is and isn’t, as it is also realistically a down-at-heel and not even shabby chic failing venture. Sally, the beturbaned manager who says she was once a beauty queen, gives Holly a job as an usher. Then we get the rest of the cast, a compilation of cranks and eccentrics, who are variously punctilious, obsessive, bone-idle, larcenous, nostalgic and on drugs, as well as the elderly owner with her own romantic backstory. Rather than just being a canter through variously out-of-kilter characters, the novel requires an engine of alteration. This comes when the owner dies, and the family sells Paradise off to a corporate behemoth. There is an enemy now, over and above the cast’s ability to self-sabotage.

One aspect extremely worthy of note is the description of working life, both in the half-haunted original Paradise and its commitment to “classic films” as well as money-spinning blockbusters and in the slick, heartless, micro-managed latter part. Work is often not really part of novels, with a few notable and important exceptions. Grudova imparts an almost Swift like disgust at the menial tasks: not just spilt popcorn, but syringes, stains, visceral descriptions of toilets and their many non-lavatorial purposes, pilfering and suchlike. When it flips into CCTV trained on the staff not the clientele, pusillanimous demands and a new boss who seems like a CGI version of a human, it becomes darker.

There is a clever structural “necessary quirk” to the book, in that each chapter is prefaced with a film title, director and release date. As a book set in a cinema, it will already appeal to those who like film, but this works as a device as the reader has to riddle the connection between the heading and the action of the plot. Sometimes it is obvious – Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai as we assemble the rest of the principals, or Aldritch’s Whatever Happened To Baby Jane as an introduction to the bewildered and demanding owner. Others are more oblique, and of course, it helps if you have seen the films. There are 22, I’ve seen 13 of them. But getting a curriculum wrapped in such a smart and provocative novel seems to me no bad thing (and there are plenty more films referenced in the text).

The emotional linchpin is how the cinema’s staff of “basically unemployable freaks” develop an esprit de corps. Film is what binds them together. It is astute to counterpoise the magic lantern of the screen, that veil to another reality, with Holly’s sense that “she looked to dull to work in the cinema”. The yearning for glamour, a sense that the old-fashioned is decidedly better than mundanity, is a kind of keynote. The gothic tone is sustained by these lost individuals working in darkness, surrounded by the moving but not living forms of dead actors and actresses, seeing everything in snippets except at the illicit after-work screenings. If there is a symbolic element to the novel it might be that these ill-paid, emotionally confused, uncertain people might be in Purgatory, or more worryingly, Limbo.

It is difficult to convey this novel’s unique atmosphere because so much of it is conjured through juxtaposition and the gradual drip-dripping of references. As well as endorsements, it is always worth checking the author biography; here it opens “Camilla Grudova lives in Edinburgh where she works as an usher.” I really, really hope that a good percentage of Children Of Paradise is fiction and not reportage. I fear not.

Children of Paradise, by Camilla Grudova, Atlantic Books, £14.99