Book review: The Broken Journey, by Kenneth Roy

Young readers are likely to find the book surprising, Scotland today being very different from the Scotland Roy remembers, more open-minded, liberal and tolerant, less ready to trust the authority of the Churches and the legal and educational Establishment. He writes for instance of a time when there was fierce argument over the right of teachers to beat children on the hand with a leather strap (the tawse) or in independent schools on the bottom with a cane; a time when the police were reluctant to interfere in what was known as “a domestic”, when homosexual relations between consenting adults were illegal, and when Scotland was not yet a post-industrial country and the SNP was a fringe party, a Scotland where you were free to smoke in public places and where politicians, lawyers and journalists were rarely condemned for being drunk in the afternoon.

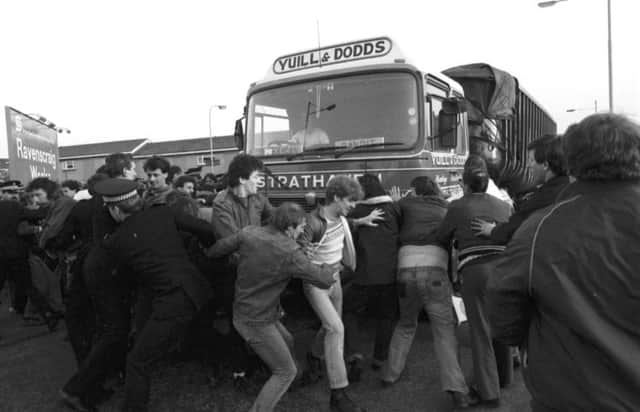

He recalls and examines things which made a great stir at the time like the Glasgow Rape Case, mishandled by the Crown Office, until a private prosecution was permitted. The political mismanagement of that affair sank the career of the flamboyant Nicholas Fairbairn, one of Mr Roy’s bêtes noires. He covers disasters, notably Piper Alpha, Lockerbie and Dunblane, for the most part fairly and judiciously. There is a balanced chapter on the miners’ strike, balanced in that he sees its tragedy while acknowledging that there were faults on both sides. There is an interesting chapter on the mysterious and still unsolved death of Willie McCrae, alcoholic SNP sometime vice-chairman; Roy sensibly reaches no conclusion. He is equally sensible in its account of the case of the Orkney children which resulted in public opprobrium being directed against well-meaning but injudicious social workers who were, he suggests, more right than wrong.

Advertisement

Hide AdNaturally he covers, more sympathetically than some, Margaret Thatcher’s “Sermon on the Mound” and also Pope John XXIII’s visit to Scotland, a recognition, among other things, of Scotland’s Catholic past, which may now, however, be seen as the high-water mark of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. Roy doesn’t stress the point but one of the features of the years surveyed here was the waning of the public power and influence of all the Churches.

Sport gets less of a look-in. He dwells with native irony on the fiasco of our vainglorious football World Cup in Argentina and on the other fiasco of Edinburgh’s second Commonwealth Games, when the despairing organisers sought salvation at the unlikely hands and tarry fingers of Robert Maxwell. But, except for the inevitable Old Firm (and the covered-up scandal of the Celtic Boys Club), that’s more or less it for sport; nothing even of the 1990 Grand Slam match against England and the improbable upsurge of bourgeois Edinburgh nationalism that day. Nor do the theatre, literature, music and other arts attract the author’s attention. Hugh McDiarmid dies in 1978, and he write amusingly about that. Still, there are nice phrases: Irvine Welsh has “left the local Bastille of learning at 16”, and Trainspotting gets a couple of pages. And yes, of course, there is a lot, an awful lot, on politics and the arguments for and against devolution, leading perhaps to independence.

In short this is a rich and fascinating survey of a country and a time which Roy views with affectionate irony. Anyone who lived through these years will find much to relish, much to provoke surprising nostalgia, something perhaps for shame. Those too young to remember the time will learn a lot about the country they have inherited. I guess many will think “whatever is wrong today, things are better now than then”.

The Broken Journey by Kenneth Roy, Birlinn, 513pp, £25