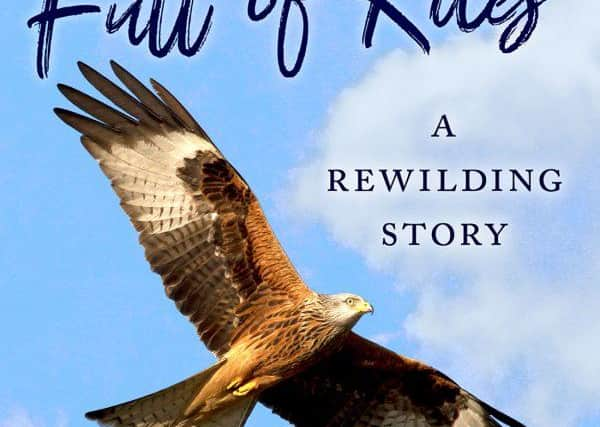

Book review: A Sky Full of Kites, by Tom Bowser

I am afraid that my patience with “nature writing” is becoming somewhat frayed. This book is subtitled “A Rewilding Story,” and it is not as if there is exactly a dearth of books on that topic. There is Isabella Tree’s Wilding, David Woodfall’s Rewilding, Benedict Macdonald’s Rebirding which won the Wainwright Prize for Writing on Global Conservation, Claire Dunn’s Rewilding The Urban Soul, Roy Dennis’s Restoring The Wild, George Monbiot’s Feral , Alice Vincent’s Rootbound – and that is before we might consider the works by Robert Macfarlane, Kathleen Jamie, Katharine Norbury, Amy Liptrot, Mark Cocker, Esther Woolfson, Helen Macdonald and others. So the question is: does Bowser bring anything new to the overcrowded table?

The elevator pitch is pretty simple. Bowser has not succeeded as a journalist, and returns to the family farm of Argaty in Stirlingshire. Some red kites have been successfully reintroduced to the area and are nesting there. They are “big birds with shining orange plumage, black and white gloved wingtips and a tail shaped like a serpent’s tongue.” Bowser is “dumbstruck” and “in that moment, everything changed.” These kites are “flaming orange” and have “scorching colours.” So it is pretty much nature-epiphany with added interest in the fact that kites had been extinct in Scotland (though perhaps not extinct-extinct) for a century. But there is many a slip between pitch and execution.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe literary editor I first worked for, the novelist Andrew Crumey, once gave me some sage advice. He said always take the non-fiction, because even if the book isn’t that good, you’ll learn something. Bad novels only teach you how bad novels can be. He was right, and I did learn things from this book. I like facts about migration, moulting, the communal nature of birds and their feeding patterns. Many of the best bits of this book are the historical references and the brief history of kites in literature and history. So it is good to know that an 18th century person would receive 2s6d for the nest of a common kite and 1s0d for a cat shot on the muir. The “gled” as the kite was known in Scots makes numerous appearances in poetry, usually in a derogatory way, and this is all interesting material.

I imagine in the elevator pitch that man sees bird would lead a publicist to query “where’s the human interest here?” There are peculiar asides. A friend leaves his employ, and Bowser finds it difficult. There are references to depression, awful emptiness, and how he “wanted this wild world, this connection to something more primal… I needed it”, rather than “cosy domesticity.” (This aversion to cosiness does not, of course, extend to sentimental anecdotes about his family). I would rather have read his ancestor’s diaries, which seem intriguing from the quotes that we get. But there is little specificity about the nature and reasons for Bowser’s ennui, the force behind the motivation to take on new projects the whole time. As they say on the trains, mind the gap.

Having set up a small literary festival we are given some blurbs about the writers. This is embarrassing. Of one nature writer he writes about marvelling – there is always a lot of marvelling in this kind of book – about “understanding how the words build the sentences, the sentences the paragraphs, I realised what an immense act of construction our best authors do.” We then get a pointless anecdote about what the author signed in a book for him.

The reintroduction of species which have been driven out is an emotive topic, and a divisive one. Having the red kites back, Bowser becomes obsessed with red squirrels, then pine martens, then dragonflies. All well and good. He lets us know that they killed 150 grey squirrels in a year because they are invasive, non-native and toxic. That kind of language gives me the shudders. He admits to the irony – a conservationist with a gun – but the problem runs far deeper. There is an idea in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant called then categorical imperative. Basically, if something is wrong, it’s wrong always and everywhere. Who decides which species is worthy of conservation and which gets a bullet in the head? I might as well set up the Royal Society for the Protection of Plankton and use it as an excuse to harpoon a whale by the arguments set out here.

The core here is “To make our home a home for wildlife. That was our goal. Because we could. That was our reason. And should any of this seem pious, false, too earnest to be credible, I should also make this confession: it probably is. I know that we have more than others, and I do feel bad about that. Doing something positive with my privilege is my best means of quelling the guilt.”

Fine words indeed. I am sure it makes all the difference to the non-red squirrels. Nature, as Tennyson said, is red and tooth and claw. We are all compromised and complicit.

A Sky Full Of Kites, by Tom Bowser, Birlinn, £14.99

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions