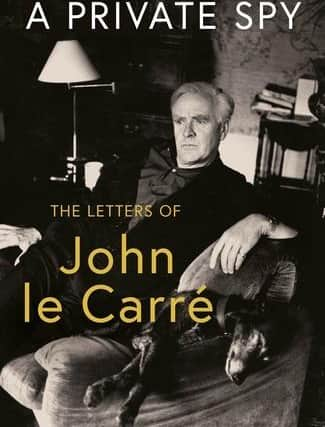

Book review: A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carré 1945-2020, edited by Tim Cornwell

One wonders for how long there will be collections of letters like this. The first letter from David Cornwell dates from 1945, the last from November 2020, shortly before his death. He wrote most of them in longhand, as he did his novels; he had never learned to type. Though he was known to the world as John le Carré, he signed off most “as ever, David.”

The book was edited by his son Tim who, sadly, didn’t live to see it in print. There is a nice mixture of the personal and professional in the collection. I say “a nice mixture” though the personal ones and those written before the publication of The Spy who Came in from The Cold made him famous are livelier and more interesting than those from the later years. Some of those dealing with research for novels will probably be of more interest to critics and biographers than to the general reader.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe had a disturbed and distressing childhood. He was five when his mother abandoned him and his elder brother. His father, Ronnie, was a con man and crook, charming, extravagant and exciting, but also utterly selfish, dishonest and unreliable; a magnetic personality and a disaster. In and out of prison, he flew high in in the spiv's post-war world, but his bankruptcy when David was not yet 20, though painful and embarrassing, gave him a sort of freedom. Supported by his Oxford tutor and Ronnie’s second wife, Jeannie (to whom he wrote many of his best letters), he cut himself free. Already fluent in German, studying in Switzerland, he was a natural target for the intelligence services. Of course, Ronnie’s boy responded; how could he not?

Ronnie never read a book, but David would become a novelist. The letters chart his development, reveal also his contractions. Married twice, the second lasting more than 50 years until his death, he was a loved and loving but unfaithful husband. Letters to and from lovers are few in this collection. He was a fond and caring father and brother, a man with many friends, yet always, I think, on the evidence of his letters, essentially alone. He was a patriot who came to distrust the British establishment and detest our political subservience to the USA and its global aggression. Most of his late novels sizzle with resentment and disapproval.

A collection of letters on this scale invites assessment or re-assessment of his work. There were 25 novels, all readable, half a dozen outstanding. He disliked being labelled a Cold War novelist and resented the suggestion that, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, he was deprived of his best material. Yet he was more closely chained to this sort of material than was Graham Greene, whom he first regarded as his master and came to be jealous of.

Some of the early novels will surely last – The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People (my own favourite among his books) – as will A Perfect Spy, which is enriched by memories of Ronnie, Our Game and The Night Manager, while I also think well of A Most Wanted Man. Yet one has the impression, which nothing in these letters disturbs, that in the last decades of his work the novels were made from research rather than experience and memory – an impression that is confirmed by requests for information as to what might be possible in a certain place, or the circumstances in which a particular character might live.

Nevertheless, even the driest of these later letters are of interest, fleshing out le Carré’s way of working. Indeed, they are evidence of his commitment to his work. At the same time, they give a revealing picture of his daily life, his interests, tastes, commitment to family and friends. So, despite some boring passages and a certain lack of the spontaneity that characterises the great letter writers, this book will appeal to his many admirers. It reveals much about the man. He had a high idea of his own worth, was more capable of great generosity than many and contrived to live his life on his own terms. I could only wish that his publishers has issued these letters in two, or better still, three volumes, rather than in this heavy monster.

A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carré 1945-2020, edited by Tim Cornwell, Viking, 703pp, £30