Book review: A Heart Full Of Headstones, by Ian Rankin

OK, I confess. I love reading crime fiction – I am particularly fond of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novels – but I am tepid about reviewing crime fiction. The reviewer basically becomes the stereotypical bent copper. “So, who did it?” “No comment”. “Is there any dramatic twist?” “No comment”. “Has anything occurred to individuals whom we have had under observation for 35 years?” “No comment”. “Is there anything you can share with us?” “I’d like to speak to my solicitor, please”.

What can one say? Well, the cover has a grab-line – “The truth will come out. And it will bury John Rebus”. It opens with Rebus in the dock, charged with something but crucially the reader does not know what. It loops back to a completely different set of investigations, before we return at the end to the court: it is not a spoiler, since the author said it on broadcast television, but there is a cliff-hanger. The Scotsman reported at the beginning of this year that Rankin had signed a two book deal for Rebus works. This is the first, and it seems to have been written with the second in mind. After that, it’s anyone’s guess.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn terms of the plot, Big Ger Cafferty, now in a wheelchair, issues a summons to Rebus, asking him to look for a man back in town whom he is widely rumoured to have had murdered. Why Rebus takes this commission is slightly opaque, and Cafferty’s reason – that he wishes to make amends – was always a dubious proposition. You don’t need to be Rebus to have suspicions. At the same time a former policeman, Haggard, is due to stand trial for enthusiastic wife-beating. His defence is that he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder brought about by having been in the force, and in particular in Tynecastle Station. Beans are threatened to be spilled, which might implicate one John Rebus. The two stories intersect, of course. Then as well as Siobhan Clarke, Malcolm Fox is back, keen to nail as many dodgy officers as he can. I rather like Fox: the grizzled, ill Rebus bent rules but did not break them; Fox is a stickler and a sook. Siobhan seems to carry on, cautiously, except for her friendship with an online journalist, of the Courant, who seems to have the scoop on all the possible corruption and yobbishness in Tynecastle. Everyone is either second-guessing someone or being economical with the truth.

One of the virtues of Rankin’s writing is that crime is always, eventually, grubby and venal. Although Rebus might conjure huge conspiracies, the truth is usually far more banal, and involve those old devils, lust and money. I still think Exit Music is one of his finest novels, and this has a family resemblance to it.

What of Rebus though? There is a brief but significant exchange where Rebus says “You sound tired, Siobhan”. “Do I? Maybe I am”. That sense of lassitude suffuses the novel. Covid is in the background, the possible corruption is dismissed as being not as bad as the Met. Rebus is, like another character, “fuelled by shame or self-preservation”. The days of harum-scarum treks across Scotland seem to be gone, and Rankin writes well about dealing will chronic illness. It does not seem coincidental that Rebus’s lawyer is called Bartleby, named, I assume, after Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, with his mantra “I would rather not”.

Rankin is always fluent, always engaging, always ready to throw a spanner in the works towards the end. This is no different, even if the gloaming seems ever darker. For readers in Scotland, and especially Edinburgh, there is the added pleasure of recognition – although personally, I’d have used the Old Chain Pier rather than the Starbank for one reference. Has Rankin given up on Rebus? Well, not yet. Siobhan is a good replacement, and I would not mind seeing a return of Todd Goodyear. There is a new villain as well in the form of a former policeman turned car-dealer, Fleck – perhaps a reference to the late Alasdair Gray’s version of Faust? Also, Cafferty has a very sinister “assistant” after the previous novel and I do not think we have seen the last of Audi Andrew.

Crime novels are in a terrible cleft-stick in that they have to be the same and they must be different. Rankin manages this with poise. Are things familiar? Yes. Are there surprises? Yes. Rebus in a strange way is Edinburgh’s guilty conscience, aware of horrors, attempting to do right. Moreover, the gap between injustices and crimes is put into clear light here. The dark may be closing in on Rebus, but he was – and still is – a kind of kindly light.

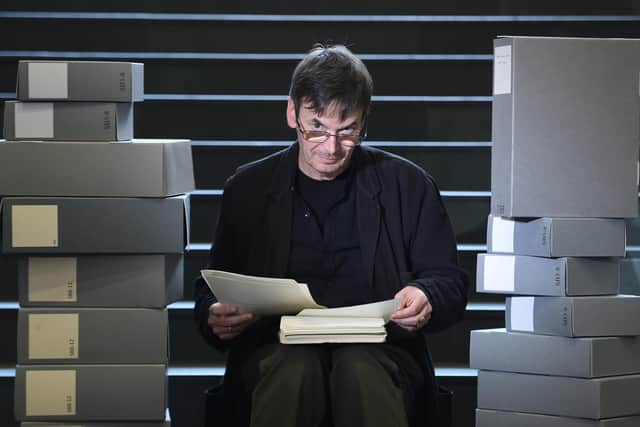

A Heart Full Of Headstones, by Ian Rankin, Orion, £22