'A Certain Stickiness' – The Most Memorable Books of 2021

It would be exceptionally easy and terribly lazy just to rattle off the books I have enjoyed in the past year. There were superb pandemic works, surprisingly, by Ewan Morrison and Sarah Hall; James Robertson made a collage of refuge and exile across centuries of Scotland; Gwendoline Riley was typically spikey; Denise Mina took a sharp poniard to Rizzio; Alan Warner was on a grotesque frolic through 70s music; Jenni Fagan gave us a demonic doll’s house with Luckenbooth – and that’s off the top of my head before we get to non-fiction. So I thought I would do something different and went to the toilet. It is the only room without any books and I could sit in quiet contemplation and a tranquil frame of mind, not cheat by checking shelves and think: what has stayed with you this year?

That was the initial problem. Time has become all porridge-y, and for the life of me I can’t remember if, say, Jeff VanderMeer’s novel Dead Astronauts came out this year or was it his ecological catastrophe Hummingbird Salamander this year, or 2020, or 2019 for that matter. As a reviewer, I read more than I review, so this is a personal note of works which had a certain stickiness.

Advertisement

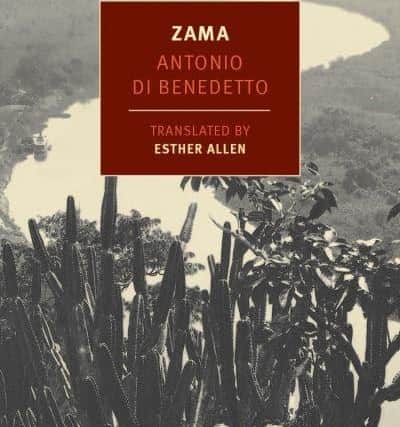

Hide AdFirst off is a book published first in 1956, but only recently available in English through the wonderful New York Review of Books imprint: Zama by the Argentinian author Antonio di Benedetto. I had never heard of him, but read this agog. It is set in the late 18th century and features one of the most hideous narrators with whom I have spent much time. The titular Don Diego de Zama is petulant, frustrated, incompetent, quick to take offence and ineptly lascivious, longing for a more serious position which he thinks befits him. There is a dreamlike quality to being stuck with this monster, and di Benedetto manages to make him pitiable in his sorry vices and someone for whom the reader feels pity.

Then I received di Benedetto’s second volume, which, if all things were equal would be in my preview of 2022 and it comes out in January in Esther Allen’s translation, The Silentiary. Again, I was wrong-footed and discombobulated, in this story of a man in a bureaucratic, minor position who is assailed by noise and manages to ignore violence. He dreams of being a crime novelist, but realises he cannot accomplish this without committing a crime. It is a knot of a book, and again di Benedetto’s prose is startling: I haven’t read sentences like “I mused with bitterness – and perhaps without justification – that if they don’t mind having their thoughts disrupted, it’s because they don’t think much”. There is a third volume, The Suicides, hopefully appearing soon. The easy comparison would be Kafka or Camus, but the comedy is darker, the wit sharper and the grammar more evident of a mind in turmoil. Seek him out.

Charlotte Higgins wrote an elegant book on labyrinths, Red Thread, which in retrospect seems like an overture to her Greek Myths. Notice the absence of a definite pronoun. Unlike Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths, this is a more slippery and evasive account of various heroines of Greek literature. Higgins extends the metaphor from Red Thread of the ribbon that lets you plot the way through into a much more extensive version, with Helen of Troy weaving a tapestry of the war as the war happens (Instagram in Attic), as a way to move through shifting stories. It is exceptionally well researched – I often thought, “You’ve made that up yourself” only to find a precise footnote. The prose is almost neoclassical, in being limpid and allusive, clear and nebulous at one and the same time.

Richard Beard is one of the most interesting writers of the moment. He has written novels, but also about a trans friend, rugby, the death of his brother, the Biblical Lazarus and a Le Carré version of the deaths of the apostles. His new work is an indictment. Sad Little Men is a no holds barred account of private boys’ boarding schools, and the combination of abandonment, sadism, entitlement and neediness they foster. Not for nothing did the heir to the throne refer to his time in one as being in “Colditz with kilts”. It has a great deal of empathy – we do not often choose where we are schooled – and an equal amount of anger, and he analyses what that form of education means, and how it now forms those who form policies.

Finally, my book of the year, and it is a bit of a googly; not that I played cricket at school. Henry Eliot’s The Penguin Modern Classics Book is as close to pornography as you can get as a bibliophile. From one angle it is a testament to book design over nigh on a century. On another, it is a work of publishing history – when did 20th Century Classics become Modern Classics and when did Classics upgrade to Modern Classics? It’s sheer delight. I pity my parents as I have made a list of 38 “need” books, and over 70 “want” books. Any imprint that can have Katherine Mansfield alongside Molesworth and Felipe Alfau next to Ian Fleming shows that the battle is not lost.

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions