Book reviews: The Zhivago Affair| Friend & Foe

The Zhivago Affair

Peter Finn and Petra Couvée

Harvill and Secker, £20

It is also a full and multifaceted account of Pasternak’s career and a study of the vicious, devious Soviet campaign against Pasternak, his supporters and his loved ones.

The Zhivago Affair works on two levels. To begin with, it really is a thriller, a page-turner. Pasternak, we are reminded, was very much the public poet, meeting with Trotsky, corresponding with Stalin, reading to packed auditoriums, then travelling across the country to meet poets and their families. But he had bitter enemies, particularly the Union of Soviet Writers bureaucrat and poet, Alexei Surkov. He also had a complicated domestic life. His second wife, Zinaida, ran their home efficiently, but was uninterested in his poetry, a role that was taken on by the young and glamorous Olga Ivinskaya, a literary editor who becomes his lover and is regarded by many as the inspiration for Lara in the novel.

Advertisement

Hide AdFinn and Couvée’s book is also an original piece of investigative reporting on how the Cold War cultural struggle developed during the 1940s and 1950s. Radio was an early battleground. Leaving aside the more innocuous Voice of America, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberation were a worry for the Communist countries. “In 1958,” the authors point out, “the Soviet Union was spending more on jamming Western signals than it spent on its own domestic and international broadcasting combined.”

The CIA’s exploitation of liberal opinion in the West during the Cold War, funding journals and sponsoring student groups, has long been known, but The Zhivago Affair reveals how it also prepared books to be smuggled behind the Iron Curtain – indeed, sometimes over the Curtain, with balloons carrying bundles of books.

A different technique was used to get a Russian edition of Doctor Zhivago into the USSR. To ensure that the Soviets would not suspect the Americans, the CIA linked up with Dutch intelligence and had the books printed and published in the Netherlands. This operation continued with nearly 400 Russian language copies of the novel being distributed to Russians via the Vatican Pavilion at the 1958 World Fair in Brussels.

That was also the year the Nobel committee decided to offer Pasternak the prize for literature – which he understandably accepted. The full force of the Soviet machine, from Nikita Khrushchev at the top through to the KGB and the Writers’ Union, was brought to bear on him until he had no option but to backtrack and refuse the award. He was a broken man and died, cancer-ridden and with a failing heart, in 1960.

The pain of the affair continued after his death. Attempts to get some of Pasternak’s western earnings to surviving beneficiaries in Russia went disastrously wrong; money was smuggled into the country where it was either lost or seized by the KGB. Ivinskaya (suspected by some of being a KGB dupe all along) was tried in secret and sent to the gulag, and an Italian team involved in publishing Pasternak’s work fell out amongst themselves, one of them linking up with the Red Brigades and then blowing himself up in a botched sabotage attempt on an electricity pylon.

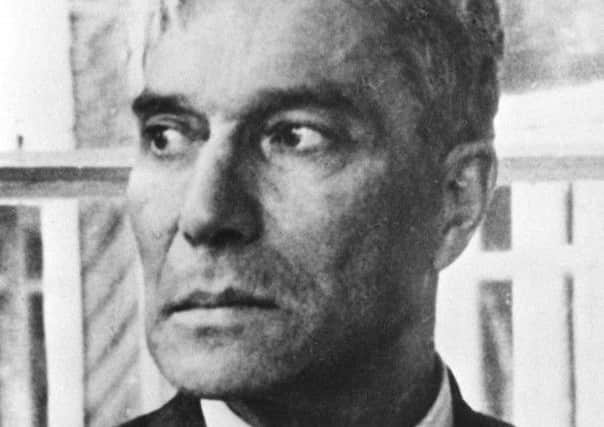

This book’s wealth of detail is important, though it also makes demands on the reader. It is well illustrated with relevant photographs of all the major participants, and has 83 pages of acknowledgements, notes on sources, endnotes, bibliography and index. With the Russian names in particular, regular checking of the photographs, notes and index is required to keep track of everyone.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe aftermath was poignant. In his seventies, deposed and in obscurity, Khrushchev was given a samizdat copy of Doctor Zhivago by his son. He took a long time to read it. “We should never have banned it,” he said, “I should have read it myself. There’s nothing anti-Soviet in it.”

Moscow Branch Writers Union members who had voted to expel Pasternak in 1958 could not forgive themselves. “That I spoke out against Pasternak is my shame,” said one. The chairman later spoke of the blot that could “never be washed away”. Not even the tears shed by Pasternak’s son Yevgeny when, in Stockholm in 1989, he stepped forward to finally accept the 1958 Nobel Prize for Literature on behalf of his father, could do that.

A Capital View: The Art Of Edinburgh

Alyssa Jean Popiel

Birlinn, £25

Advertisement

Hide AdEDINBURGH has always been the kind of city that makes art look easy. Even those of us who have never dabbed brush on canvas can get carried away by its sheer physical drama and imagine it really wouldn’t be that hard to capture it in any variety of painterly styles.

The slow sweep of light on the north-facing slopes of Arthur’s Seat, such a shocking expanse of green as you emerge from tenement streets? I’ve seen it so many times, but now realise that Claude Buckle got there before me for his 1960 railway poster. The way, viewed from Princes Street on a late winter’s evening, the buildings around Cockburn Street seem so foreshortened, like a Vorticist stage set? Adam Bruce Thomson’s 1930s painting of North Bridge and Salisbury Crags beat me to it.

Anyone who knows Edinburgh will have similar mental images of it to paintings that can be found in its City Collection, which as both this book and the current exhibition at the City Art Centre make you realise, is one of the most wide-ranging in these islands. However, the real interest in both lies in images of Edinburgh that we couldn’t begin to imagine.

Without William Delacour’s 1759 painting, for example, would we realise that Enlightenment Edinburgh had clouds of smog above it? Without Thomas Donaldson’s 1780 etching of a view of the North Bridge, would we have any notion of what the future Princes Street Gardens looked like when cattle roamed on the fields before the railway cut through them?

There’s so much more here, in paintings that are beautifully presented and excellently explained. Imagine what the Mound looked like before Playfair got his hands on it and you’re probably not envisioning a peep show and an elephant advertising a firework display, but that’s what you get in Charles Halkerston’s 1843 View Of Princes Street. Or imagine, as in William Reid’s mid-19th century painting, a Leith with a vast expanse of sand instead of docks, where le tout Edinburgh gathered for its biggest sporting occasion – the Leith Races – with vast crowds gathering in front of the kiln-like glassworks chimneys on the shore. All gone, all forgotten – and all, therefore, that much more of a surprise to see again.

There are paintings here of great artistic merit – portraits by Cadell and Gunn that would grace any national collection, and Sir Stanley Cursiter’s wonderful Pachmann At The Usher Hall – but I don’t think that is completely the point. What counts here are a series of portraits and panoramas of a city you may know well but haven’t seen before and can hardly imagine. The shock of the old, in other words – Auld Reekie as you haven’t seen her before but really should. David Robinson

Friend & Foe

Shirley McKay

Polygon, £12.99

Advertisement

Hide AdIN SHIRLEY McKay’s engaging series of historical crime novels, Hew Cullan, lecturer in law at St Andrews in 1583, helps the coroner to solve the occasional murder. He’s quite good at it too and it makes a welcome change from the fullness of his real job.

The fourth book in the series opens on May Day – always a cheerful occasion but even more so this year as Andrew Melville, principal of St Mary’s College, is away in Edinburgh at the Kirk Assembly.

Advertisement

Hide AdOn his return, there is a good attendance at his lecture on marriage but as the crowd leaves, blood is spotted on a hawthorn tree.

Samples are taken by Hew’s brother-in-law for a primitive form of analysis to determine whether it is human.

There is a suggestion that the matter might be linked to the tension with St Leonard’s College over syllabus revision, which just goes to show how little academics have changed.

Hew also finds himself deeply involved in the politics of the day. The teenage King James VI is in the custody of Lord Gowrie and is planning his escape.

When Esme Stewart, first Duke of Lennox, the king’s favourite, dies in exile in France, his heart is returned to Scotland. The king wants the heart to be put on trial to establish that Esme was not a traitor, and he calls on Hew to lead the defence case.

This frankly weird request takes second place to the murder, rather late in the book, of Harry Petrie, a college servant.

Advertisement

Hide AdHew is needed to solve that before term ends. There had been suggestions that the terms should be lengthened “to keep the sons of gentle folk from sluggardry and sloth” but this proves too costly. Little, it seems, has changed on the student front either.

The college manoeuvrings might not work for a crime novel set in the present day but here they definitely do, and the novel’s credible mixture of English and Scots charms the reader.

Let’s hope Hew returns soon. Douglas Osler