Book review: The Sports Gene

THE SPORTS GENE

by David Epstein

Yellow Jersey, 252pp, £16.99

While he himself would “chew through a crowbar” to shave off a quarter of a second from his time, running seemed to come naturally to his friend. Was the difference between the two genetic? Could David’s grit and determination overcome his apparent lack of innate ability? Where does the intersection between talent and practice lie?

These are the questions Epstein seeks to answer in this captivating book. It does, however, have a misleading title as he forcefully argues that no single known gene is sufficient to ensure athletic success. His answer to the question “Nature or nurture?” is both.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe book traces Epstein’s search for the roots of elite sport performance as he encounters characters and stories so engrossing that readers may not realise they’re getting an advanced course in genetics, physiology and sports medicine.

Investigating the theory that practice is what distinguishes professional athletes from amateurs, he meets a golf novice, Dan McLaughlin, who quit his job to test whether 10,000 hours of practice – called the “magic number for true expertise” in Malcolm Gladwell’s best-seller Outliers – could transform him into a top pro. (He started in 2010 and is less than halfway to 10,000 hours; by June, his handicap was 5.5.) Whether (and how fast) chumps can become champs depends on their baseline ability and how rapidly they improve – factors highly influenced by genetics. After months of identical training, some athletes make almost no fitness gains, while others increase their aerobic capacities by 50 per cent or more. Scientists have identified more than 20 gene variants that can separate high responders from low ones.

Epstein argues that we often confuse innate talent with spirit or effort. Even traits like desire may arise from DNA but that does not mean they come down to any single gene. Whether it’s running faster, standing taller or jumping higher, multiple genetic pathways may lead there.

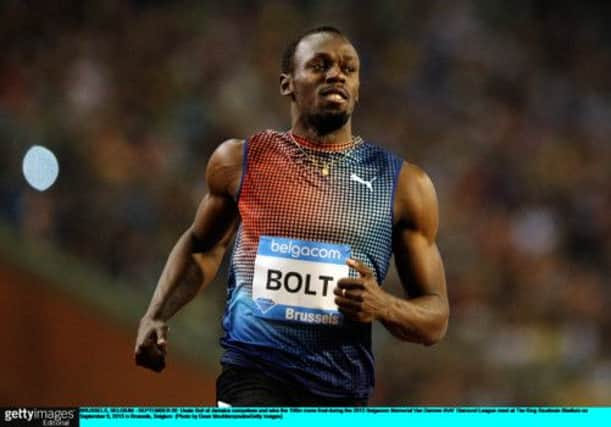

In a particularly fascinating chapter, Epstein investigates an old theory that purports to explain why Jamaica produces so many Olympic sprinters. The notion is that strong Africans were selected as slaves, that the strongest of them survived the voyage to Jamaica, and that the strongest survivors eventually escaped slavery and cloistered themselves in a remote region to form an isolated “warrior” gene stock that now produces world-class athletes.

It makes a good story. But it is belied by the DNA research of Yannis Pitsiladis, a biologist at the University of Glasgow, who finds no genetically distinct subgroup of Jamaican sprinters. It appears that Jamaica churns out sprinters because almost everyone on the island tries the sport.

Recent positive drug tests from two prominent sprinters may also help explain Jamaica’s dominance, and it’s disappointing that the book devotes little space to the interplay of doping and genetics. But the omission is easy to forgive in a book that covers so much ground.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn light of the research on trainability, Epstein revises his own history. He and his friend Scott ran the same workouts and pushed themselves to the point of vomiting, so perhaps Scott wasn’t more talented after all. They were just born with different gifts.

Epstein speculates that he had low baseline ability but a rapid training response that allowed him to improve quickly, while Scott began with a high level of baseline talent but less potential to improve. Yet it was David who got credit for guts and grit, while Scott was written off as a head case who was squandering his talent. Narratives matter, Epstein argues, and many of the ones we tell are flat wrong.

Advertisement

Hide AdCorrecting these false stories won’t be easy. In the final chapter, we meet Eero Mantyranta, a Finnish cross-country skier and three-time Olympic gold medallist born with a genetic mutation that gives him an extraordinarily high red-blood-cell count. Though scientists can show that this confers a significant advantage by allowing his blood to carry more oxygen, Mantyranta could not be convinced. It was his “determination and psyche” that made him a champion, he says – his blood had nothing to do with it.