Book review: The Golden Thread: The Story of Writing

Ewan Clayton’s fabulous account of the evolution of the Roman alphabet we still use is always alert to the differences and similarities between print and penmanship. It is a dual history, of fonts and quills, typefaces and inscriptions, with one eye on the fact that we are in the midst of a seismic shift in, for want of a better word, lettering. While providing a broad overview, Clayton – a former monk, consultant for Xerox PARC, calligrapher and professor of design – punctuates his history with such wonderful anecdotes as the fact that Nietzsche used a Hansen Ball typewriter; that Julius Caesar may have been an “early adopter” of the codex and that John Schooling was one of the first people to try to analyse Napoleon based on his changing signature (I should mention my friend Robert Douglas-Fairhurst has written wisely and wittily on how Charles Dickens developed his autograph).

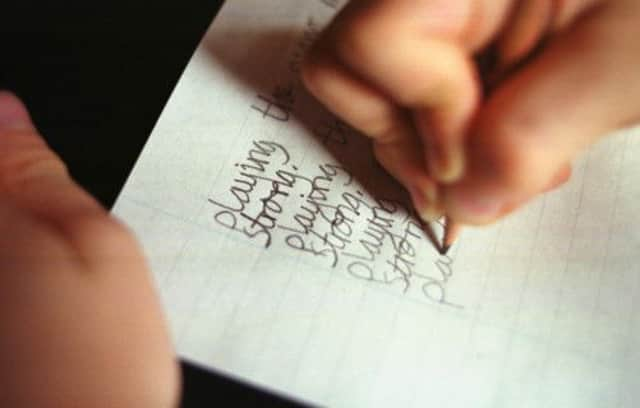

Like most people of my generation, I suppose, I am appalled at how bad my handwriting has become. I used to have – if I say so myself – a very elegant cursive verging on the Spencerian: it is now a hasty squiggle tending to the upright. As Clayton shows, all handwritings develop under pressures of speed versus legibility, from Uncial in the era of Charlemagne to the italic and round hand of the 18th and 19th centuries. When print comes in to play, there is a move for handwriting to mimic type, though, as Clayton shows, type first imitated handwriting.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe interplay of text and calligraphy sets this book apart from others in a similar vein. It is slightly surprising – though given its limitation to the Roman alphabet, understandable – that Clayton does not discuss Alessandro and Paganino Paganini, the Venetian entrepreneurs who published the first printed Qur’an using moveable type. Every copy was thought destroyed – through Papal injunction, divine intervention or the Ottomans finding too many mistakes in the copy, a blasphemy in Islam – until one turned up in the Frati Minori di San Michele, confirming its error-ridden nature. The lack of a printed Qur’an led to great achievements in calligraphy. The presence of a printed Bible made the Reformation. One wonders how history might have twisted had the Paganinis spent more time proof-reading.

Whether chiselled, scrawled or typed, letters carry with them extra meanings. A handwritten thank you letter is different from an e-mail with the same words; the classical rigidity of the lettering at the late Iain Hamilton Finlay’s garden, Little Sparta, would be inconceivable in Matisse ITC. The great trick of great public writing – the mechanical process, not the content – is to disappear while profoundly changing the reader’s mind. It is an etiolated version of handwriting itself. I can think of several people (my cousin, my neighbour, my late grandpa, my P5 schoolteacher Mrs Bowd) whose handwriting is inimitable and gloriously their own. And, Mrs Bowd, I still try to do a capital M like you.

The latter sections of the book, dealing with the digital revolution, makes a strong claim for the written co-existing with the typed, while acknowledging the futility of predictiing the future. To take two examples: creating lettering for road-signs is far more complex than one might imagine (distinguishing, for example, an l from an I from a 1), and relies heavily on design. Secondly: do you remember ASCII, the earliest version of digital text? It has now evolved into its own, Oulipo-style, art form; and without it the various emoticons (;-> etc) would not exist. Whenever people create letters – on clay, papyrus, paper, or online – innovation is not just possible but inevitable.