Book review: The Broken Road

THE BROKEN ROAD

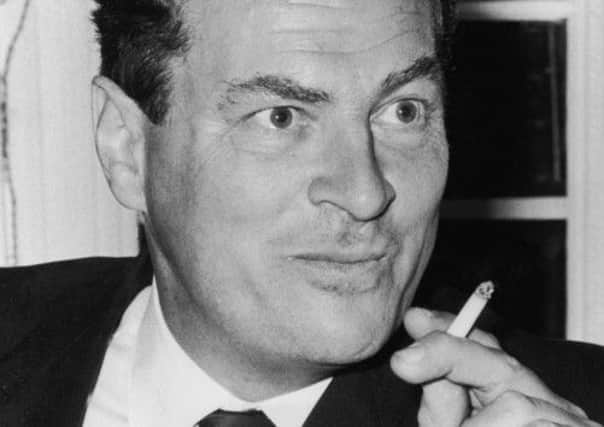

by PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR

John Murray, £25

With many diversions and congenial breaks in the company of woodcutters and aristocrats, the journey took him a year. Decades later it became apparent to Leigh Fermor and others that he had not only crossed the continent on foot; he had traversed a Europe which was on the brink of irreversible social and political change.

It nonetheless took him a while to write about it. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s literary career was delayed by his characteristically flamboyant wartime activities with the Special Operations Executive. After the Second World War he spent time in the Caribbean. He published his first book, The Traveller’s Tree, about the West Indies in 1950, when he was 35 years old.

Advertisement

Hide AdLeigh Fermor settled in Greece and his next two books of serious note, Mani and Roumeli, were gorgeously articulated expressions of his love affair with his adopted country.

They also took an ominously long time to write. Mani was published in 1958 and Roumeli in 1966. That was partly due to Leigh Fermor’s painstaking search for stylistic excellence – Melvyn Bragg would later suggest that he was “trying to write the perfect book”. It was also because the author was at least as interested in living the perfect life, which involved heroic quantities of wine, women and song.

A further 11 years lapsed before he considered his account of the first third of his pre-war walk to be fit for print. A Time of Gifts took him from Holland through the simmering early months of Nazi Germany to the border between Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The second volume, which walked from Czechoslovakia to the Danube’s Iron Gates gorge between Serbia and Romania, was titled Between the Woods and the Water and published in 1986.

The exuberance, off-the-wall scholarship, characterisation and teenaged derring-do of those two books initiated and rode the high wave of the 1980s travel writing boom. Patrick Leigh Fermor was garlanded with praise and internationally recognised as one of the greatest of 20th century authors.

The world, not least that part of the world occupied by his publisher John Murray, held its breath and waited for the third and final volume. Leigh Fermor was 71 years old in 1986. But he enjoyed robust good health in his Peloponnesian retreat and he had written on the last page of Between the Woods and the Water the three promising words “To be Concluded”.

There seemed at first no reason not to hope. Only slowly did it become apparent that one of the saddest cases of writer’s block in recent times had descended on that villa in the Mani. Patrick Leigh Fermor had a towering pile of notes and draft manuscript covering his passage from the Iron Gates to Constantinople, but he was unable to convert them into the book which satisfied his own unique standards.

Advertisement

Hide AdJohn Murray persuaded his author to publish collections of letters and essays. As the years passed it became clear that those were pale substitutes for the completion of what would have been an immortal trilogy. Patrick Leigh Fermor died in June 2011 at the age of 96 years. He left no third volume. He did leave the pile of notes and first-copy manuscript.

They have been worked up by his friend and biographer Artemis Cooper and his friend and fellow travel writer Colin Thubron and published as The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe editors’ title, an acknowledgement that Leigh Fermor’s literary journey was unfinished, is perfect. In their introduction Thubron and Cooper are honest to the point of apology in admitting that this story cannot reasonably compare to the finished product of Patrick Leigh Fermor in midseason form.

The sentences are almost all Leigh Fermor’s, and usually recognisably so. But as Cooper pointed out in her biography, part of the brilliance of the first two volumes lay in the fact that Leigh Fermor novelised his travels. That is not to say that he made much up. It is to say that he constructed and polished his narrative; he expertly conflated characters and relocated incidents. From the fertile ground of his own irrepressible self and his glorious adventures he cultivated an astonishing Bildungsroman in a world so lost that it may as well be fictional.

The Broken Word, on the other hand, remains a draft, albeit a draft edited by skilled and sympathetic hands. It is also a Patrick Leigh Fermor draft, which makes it superior to the finished work of most other writers. The youthful joy shines through, and the deep cultural learning that was superimposed in later years is there in sufficient quantity to lend wonder to this fragmented tale.

The book is rarely less than invigorating. At times, as when our hero finds himself riotously overnighting by the Black Sea with a congregation of Bulgarian shepherds and Greek fishermen, The Broken Road has all the verve of the finished article.

It strides towards an ideal conclusion – not in Constantinople, of which Leigh Fermor mysteriously left few accounts, but on Mount Athos. There we find the boy who would come to know Greece better than most Greeks first grasping with delight the modern vernacular and the traditional ways of a land that never ceased to captivate him, and through him, his readers.

This will be the last full book by Patrick Leigh Fermor to appear in print. Anybody who loved its two preceding volumes will fall upon it hungrily. Anybody who has not read the two preceding volumes should do so without delay.