Book review: The Adventures Of Sir Thomas Browne

The Adventures Of Sir Thomas Browne In The 21st Century

Hugh Aldersey-Williams

Granta, £15

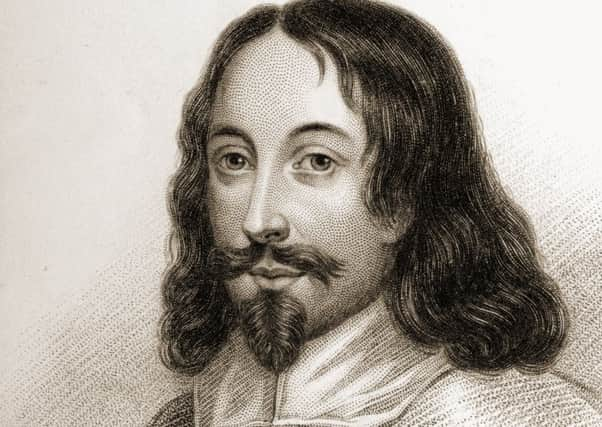

In one of those serendipitous moments that typify the world of publishing, this new book on Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), the polymathic and unclassifiable author, comes swiftly after Ruth Scurr’s astonishing book on the unclassifiable and polymathic author John Aubrey (1626-1697). Like Scurr’s book, Hugh Aldersey-Williams’ work is an experiment in the art of biography. It may be a slightly more traditional form of experimentation – it features an imagined conversation between the author and the subject, a series of footnotes on words coined by Browne, as well as copious (and beautiful) illustrations in the style of WG Sebald, a great admirer of Browne – but its sense of limitless curiosity is very much in keeping with its subject.

Browne lived for most of his life in Norwich, where he was a doctor. Among his published works were Religio Medici, an essay which attempted to reconcile his faith with his interest in medical science; Pseudodoxia Epidemica or “Enquiries into very many Received Tenets, and commonly Presumed Truths”; Hydriotaphia, usually called Urn Burial, occasioned by the discovery of a great many sepulchral urns; and The Garden Of Cyrus, Or The Quincuncial Lozenge, about the best form of tree-planting, ostensibly, but also a disquisition into mathematics and nature. He also left a number of manuscripts on ethics, the natural history of Norfolk and the sublime Musaeum Clausum, “The Sealed Museum”, a list of books Browne wished had been written but never were (such as a volume by the geographer Pytheas justifying his purported contention that north of Shetland the very air turns to cold jelly). Yes, his titles are daunting, but that last detail gives some idea of why we should read Sir Thomas Browne. He was interested in absolutely everything.

Advertisement

Hide AdBrowne was not just one of the finest prose stylists in English, counting among his admirers Johnson, Coleridge, Melville, Woolf and Borges. Among the words we have to thank him for are hallucination, electricity, presumably, migrant and carnivorous. Much of it is self-consciously Latinate, which may account for why he is read so little nowadays. But his work, and words, emerged from his engagement with the world. Browne adhered to the new “scientific method” pioneered by Sir Francis Bacon. If he heard that the desiccated corpse of a kingfisher made an excellent weathervane, he would have not one, but two, hanging in his rooms to determine the truth. He kept a bittern in his garden to nix the idea they blew through reeds (though his experiment was inconclusive) and autopsied a dead whale that washed up on the Norfolk shore. His investigations into eggs were pioneering works of embryology, and he ran medical trials to decide whether gold had therapeutic properties, or diamonds could be dissolved in goat’s blood. He was the truest kind of sceptic in that he admitted the limits of scepticism.

There are few biographical facts – or at least interesting ones, though Aldersey-Williams does begin with Browne’s testimony at a witch-trial – and much of what is of interest in Browne is in his thoughts rather than his deeds. Consequently, Aldersey-Williams structures the book thematically, looking at science and medicine, flora and fauna, religion and tolerance, death and melancholy and “objects” – like the Tradescants and Aubrey, he was an avid collector. John Evelyn recorded on a visit that “his whole house and garden is a paradise and Cabinet of rarities and that of the best collection, amongst medals, books, plants, natural things”.

Browne had a glorious capacity for digression, and Aldersey-Williams follows by comparing the debates and differences of the 17th century with similar phenomena from our own times. It’s a high-risk strategy to segue from the Civil War and the Restoration of Charles II to Jimmy Savile and Richard Dawkins, the MMR vaccine and the Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders, Morgellons and the Mass Extinction Monitoring Organisation, George Monbiot and Amanda Knox, Mercedes hubcaps and the IgNobel Awards.

For the most part, these comparisons are judicious and offer a clever shift in perspective; the most usual form of which is to caution against the unthinking assumption that we of the 21st century have outgrown the 17th. Aldersey-Williams also introduces himself into the narrative – birdwatching and cycling the route Browne took back from the witch-trial, commenting on contemporary Norwich’s lack of enthusiasm for one of its greatest figures, musing on Ukip and VAT rates, meeting the artist Michael Landy (whose Break Down involved the systematic destruction of all his possessions).

By and large, these incursions justify the book’s title – this is not A Life Of Sir Thomas Browne, but an intermingling of Browne’s fascinations with the present day, and part of Aldersey-Williams’ method is to chart his own obsession with Browne and the circuitous routes on which he is propelled by it. It is curious that Scurr’s biography took a polar opposite approach, constructing a “diary” of Aubrey using predominantly his own words and completely suppressing the biographer’s voice.

I cannot conceive of a reader who will not find some nugget of delight in this, even if they do not go on to read Browne himself. Many of Browne’s devotees have commented on his lightness of touch (despite the polysyllabic inventions) and it is a quality shared by this book, minus the propensity for neologism. I also strongly suspect that publishers must now be casting around for something on the unclassifiable 17th century polymath Richard Burton, author of The Anatomy Of Melancholy.