Book review: The Lure of the Honey Bird by Elizabeth Laird

The Lure of the Honey Bird by Elizabeth Laird

Polygon, 374pp, £12.99

In the late 1990s, Elizabeth Laird and a friend were standing on a hill above Addis Ababa watching a line of ants cross a road. A stranger came up to them, thinking that they had lost something and the friend explained about the ants. “The ant is a very good animal,” the stranger said. “I will tell you a story about him.”

Time slips away at moments like that – or at least it does for us rushing, deadline-driven westerners. We don’t have those stories of the golden age when men and all the animals could talk, stories that once could have taught us everyday survival in a wild, untamed land. We don’t gather round and listen, children open-mouthed and so attentive they don’t even notice the flies sucking at their eyes, grown-ups so appreciative that they will suck in their breath and yelp when they hear a story they like.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut they do in Ethiopia – or at least they do right now, when literacy still hasn’t completely spread across the land or the media’s blare sucked everyone into the 21st century. And as the stories they tell have echoes we can trace in the Bible, in the Koran, even in tales slaves told themselves in America, those time-slip moments can gather like a snow before an avalanche. It makes a lot of sense, therefore, to write them down before they disappear. And in Ethiopia, where all education from seventh grade onwards is now in English, it makes even more sense to use the country’s folk-tales in English language story-books that could be used in Ethiopia’s schools..

That was the idea that Laird had after the stranger told her the story about the ant as they overlooked Addis Ababa. With the backing of the British Council and the Ethiopian Ministry of Education, she travelled round the country collecting stories to turn not only into a series of books but also a website on which you can read some of the stories and hear them in their original languages (www.ethiopianfolktales.com).

I can’t think of anyone better suited to the task. A prize-winning children’s writer, Laird is incredibly well-travelled, and has lived in Malaya, India, Lebanon, Iraq as well as Ethiopia, which she first visited as a teacher as a 23-year-old in 1963. That must have been when she met Haile Selassi, was wrongly arrested for murder, and hitched across the Ogaden desert on a qat-smuggling lorry. Although – full disclosure – I know her slightly, before reading the press release, I had no idea of any of this. Which makes me like her even more than I already do.

It’s not easy, this business of collecting stories. Officials assigned to Laird can’t imagine how she could possibly be interested in peasant culture and want to show off instead the clever wordplay of their “wax and gold” proverbs, where a surface meaning can melt like wax into a deeper, golden truth. Thanks to them, she misses out on many of the women’s stories or comes across ones she’s heard already or which are straight imports from Arabia.

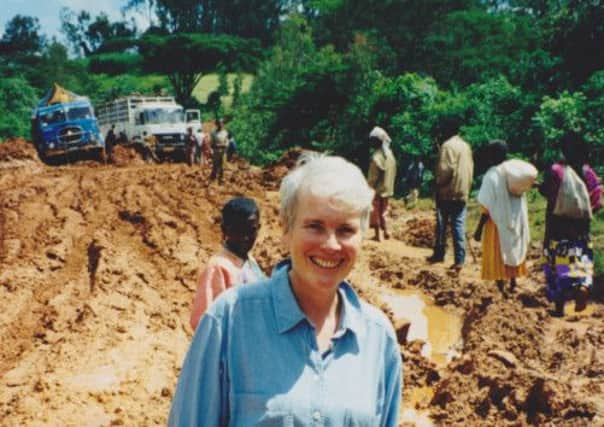

Physically, it’s difficult too. Bouncing down by Land Rover into the Danakil Depression in Afar province must be hard enough – it’s hotter there than anywhere else on the planet – without also suffering from dystentry. The road to Beni-Shangul turns out to be a sea of impassable mud. The night before setting out for Somalia, a bus had been hijacked and all its passengers taken out and shot.

And yet it’s in Afar – where until recently you were only a real man if you presented your bride with someone else’s testicles – where, after having been told stories of princes in search of clever women to marry, Laird is asked for a story herself. She gives them Beauty and the Beast and they love it, smiling at all the happy bits, sighing at the sad ones, concentrating throughout. Maybe there was one of those timeslip moments for her audience too, listening to this ferenji (the common word for Europeans, deriving from the word “Franks” and dates back to the Middle Ages) just as there was for Laird, in this remote province where our first ancestors came from (or at least Lucy, Australapithacus Afarensis did). Walking back to her squalid hotel, she realises that even though she had never been further away from the familiar, safe and comfortable, she was completely unafraid.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe stories Laird collects are weird and wonderful and sometimes quite magical. There’s a tortoise and hare story which is about sex, a version of Chicken Licken which is much infinitely better than our own (and which she is told to the accompaniment of screams from a nearby exorcism). A story about “the Lion’s Bride” is, as she points out, as surreal as Chagall’s painting of flying brides, yet contains within it utterly realistic scenes of everyday nomadic life as well as expressing a girl-bride’s fear of what will happen on her wedding night.

For all the privations Ethiopians suffer (erratic food, lack of money, political instability, lack of good health care) Laird is clearly entranced by their country. Through this loving exploration of its folk tale tradition, she does a superb job of explaining why.