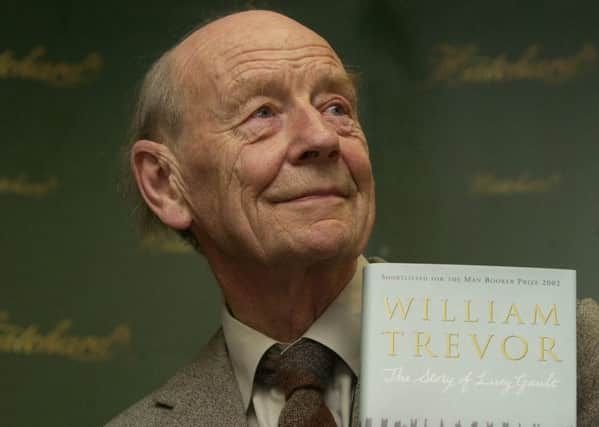

Book review: Last Stories, by William Trevor

Trevor was a great eavesdropper, a picker-up of unconsidered trifles.Most of the greatest short story writers are that: Maupassant, Chekhov, Kipling, Maugham, Fitzgerald, Pritchett – not perhaps Hemingway, whose best stories come from his own life, direct experience. All such writers need is a glimpse, a snatch of conversation overheard, and their imagination gets to work. Trevor liked, I believe, to walk away when an exchange had aroused his interest, to enable his imagination to have free play.

Many good writers – perhaps most – are in some degree outsiders, standing at an angle to experience, observing the crowd rather than mingling. Trevor was in this position perforce: a Protestant in De Valera’s Catholic Ireland, to some extent admittedly quite a privileged one, educated at Trinity Dublin; nevertheless not fully belonging, viewed with suspicion as a “West Briton”. Later he and his wife lived mostly in England (Devon) where he never, I think, forgot that he wasn’t English.

Advertisement

Hide AdForty years ago a distinguished publisher told me he intensely disliked William Trevor’s work. How on earth could he? “Because,” he said, “he’s in love with failure, he does the dirty on life.” I found this extraordinary, and still do. But now I think I understand this energetic and intelligent man’s distaste. It’s not just that Trevor has a well of sympathy for those who are broken or baffled by life. It’s also that he is suspicious of success; what uneasiness or harsh ignorance is concealed by the confident façade?

People who have endured disappointment or loneliness, or whose lives have been broken, will, Trevor knows, settle for second-best, for what they can get. ‘The Piano Teacher’s Pupil’ is an example: she discovers that her most gifted pupil is stealing little objects from her inherited, over-furnished home. Will she speak or accept the thefts as the price exacted for the pleasure his visits afford her? “There was a balance struck; it was enough.” People do not in his stories behave as sensibly as they know they should. In ‘At the Caffe Doria’, a woman resolutely rejects the attempt at reconciliation by the woman who was once her best friend – the woman for whom her now dead husband left her. She does so even though she knows she is condemning herself to the loneliness of satisfied pride.

One or two of these stories are thinner or more perfunctory than Trevor’s best – not surprising if they were all indeed written in his eighties. Short stories are often hit or miss, and there are still more hits than misses here. There is ‘Making Conversation’, where a girl is visited by the angry wife of the man who has been stalking her, a woman who cannot be brought to listen to how the girl is sure things really are.

Best of all is ‘Mrs Crasthorpe’, a story beautifully adroit in its calculated misdirection, from the moment the newly widowed woman comes away from the strange funeral commanded by her husband, and resolves to live more fully. A widower to whom she makes advances finds her vulgar and disturbing. So doubtless she is, but in two or three unvarnished sentences, and a painful visit, one understands her pathetic attempt at defiance of cruel fate, and is brought to sympathise with this woman from whom one might, like the widower, flee if encountered off the page. Like so many of Trevor’s best stories this one reveals more when read for a second time.

Trevor at his best reminds me of something Maugham once said about Chekhov: that he makes everything seem so true and natural, that it seems easy, and you wonder why everyone can’t write like that – until you try to match it.

Last Stories, by William, Viking, 224pp, £14.99