Book review: The Good Lord Bird

THE GOOD LORD BIRD

James McBride

Riverhead, 432pp, £16.99

One understands the tribute. There are indeed echoes of Twain. It is a comic novel, and an audacious one, for, set in the years immediately before the Civil War, its subject is slavery and the central figure is the abolitionist, John Brown, who was hanged after the failure of his attempt to incite a slave uprising. Making a comic novel of Brown’s story invites questions. Is it an example of a modern inability to treat history as anything other than entertainment? Or is it evidence of maturity, with Americans now confident that they have put the historical horrors of slavery and the Civil War behind them?.

Brown himself has always been a puzzling figure. The Union troops went to war singing that his soul goes marching on. His commitment to freeing the slaves was absolute, his defiant speech at his trial an expression of idealism comparable to the Gettysburg Address, and his death serenely heroic. Yet, as Edmund Wilson wrote in Patriotic Gore, his magnificent survey of the literature of the Civil War, “it is plainly on record that Brown’s family was riddled with insanity … and his relatives and others who knew him signed 19 affidavits declaring that they believed him mad.” He also murdered a family of illiterate poor whites, a slaughter he declared had been “decreed by Almighty God, ordained from eternity”. Like many with noble ideals, he was also a murderous and at least half-crazy fanatic.

Advertisement

Hide AdMcBride doesn’t pretend otherwise. Nevertheless, he dilutes it by presenting Brown as both impressive and comic, a charismatic leader whose enterprises usually end in failure, attractively tender in his relationship to the narrator, yet inflexible in his belief that “without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins”.

The novel is ostensibly a manuscript written in 1942, being the memories of an old man, Henry “The Onion” Shackleford, who claimed to have been “the only Negro to survive John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry”. Enough is said in this brief introductory note to suggest that “Onion”, whom many believed to be a woman, was an unreliable narrator. It is possible therefore to read what follows as a very tall story.

But it may also be the truth.

We meet Brown first in a barber-shop where young Henry, dressed in a smock, works as an assistant. Baited by slavers, Brown whips out a rifle and faces them down . This is a classic Western scene – Brown as John Wayne. Then he makes off, taking Henry, whom he assumes to be a girl on account of his dress, with him. Henry thus becomes Henrietta, and will be in travesty throughout the novel. This makes for comedy, but also makes a serious point: American blacks are doomed to play the part written for them by their masters, and , as Henry/Henrietta puts it, “Hiding. Smiling, Pretending bondage is OK till they’re free, and then what? Pretending to be like the white man?”

The novel is Henry/Henrietta’s story as much as it is Brown’s, and it is a picaresque tale as he runs, and escapes from, a series of dangers. Much of it is comic. His defence mechanism is to burst into tears and sigh, “I just don’t know where I belongs, being a tragic mulatto and all.” Frederick Douglass, the great black orator and champion of his race, makes lofty speeches and then, being in liquor, tries to seduce the boy-girl. Nothing is quite as it seems. Brown himself is a heroic figure, but also a figure of fun.

Any successful novel depends on its tone of voice. Get this wrong and the book fails to please or convince. It lacks the intangible, sometimes elusive, feeling of authenticity and is without authority. James McBride’s narrator is engaging and persuasive, enjoyable company. The comparison with Mark Twain is justified. Henry-Henrietta recalls Huckleberry Finn. Yet, like the best comic novels, this one also poses serious questions: what must an outsider – and all blacks were outsiders – do to survive in an alien culture? The answer for McBride’s narrator is perpetual adaptability. He/she is ready to play the different roles allotted to him/her. “I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about,” is an early response to Brown, “but, being he was a lunatic, I nodded me head yes.”

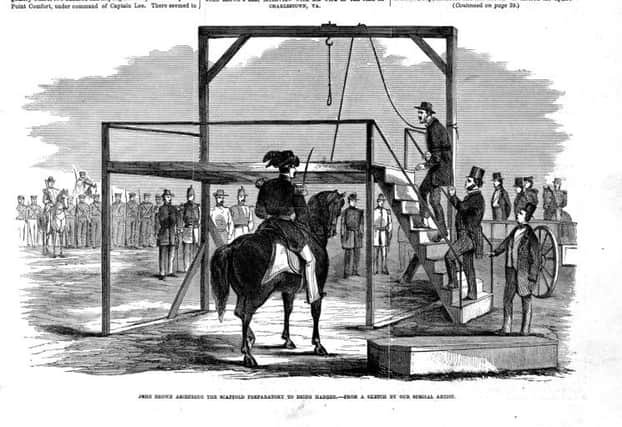

But the lunatic is also the narrator’s hero, and after he is hanged, comes this reflection about the important people who came to watch him hang: “I reckon when they got to heaven, they’d be right surprised to find the Old Man waiting for ’em, Bible in hand, lecturing ’em on the evils of slavery. Bt the time he’d done with ’em , they probably wished they’d gone the other way.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHenry/Henrietta’s last meeting with Brown is moving. He realises too that Brown knew all the time that he was really a boy just as “he knowed true inside him” that his mission “to lead the colored to freedom weren’t no lunacy.”