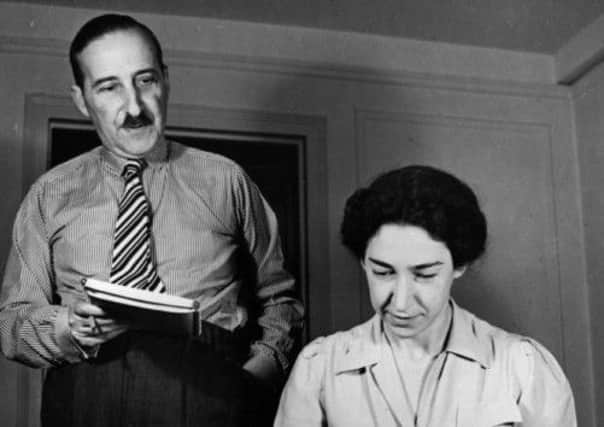

Book review: The Collected Stories by Stefan Zweig

The Collected Stories by Stefan Zweig

Pushkin Press, 710pp, £20

He has always been popular and admired in France, but never had much of a reputation in Britain, though he loved England and eventually, after escaping Hitler, settled here and acquired British nationality. One reason for his lack of success in this country may have been that his favoured fictional form was the novella, never popular with British publishers. But he was also a prolific writer of short stories – so much so that this new edition, though entitled The Collected Stories, is surely only a selection. His biographies, notably of Mary, Queen of Scots and Marie Antoinette, were successful in their time, and he wrote fluently and intelligently about a wide range of historical and literary subjects. Yet he was all but forgotten here till the Pushkin Press began republishing his work.

Even so he remains a figure who divides critics. Clive James, in Cultural Amnesia, called him “the incarnation of humanism”. On the other hand, Michael Hofmann, who as translator and critic, has done so much to revive the reputation of Joseph Roth (a close friend of Zweig’s) wrote a vitriolic review of Zweig’s memoir The World of Yesterday in the London Review of Books, in which he denounced both the man and his work as “putrid”. “Stefan Zweig,” he wrote, “just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing … He is both an absolutely natural and absolutely dreadful writer.” And so on.

Advertisement

Hide AdHofmann is way over the top; that is obvious. The question is why Zweig so irritates him and why he has had as many detractors as admirers. One reason is that he was born rich, never had to struggle; another that his quite remarkable fluency, versatility and commercial success arouse suspicion. Somebody for whom writing always seemed to come easily can’t – surely? – be much good. Yet you can’t get away from the fact that many people love his work.

This collection of stories and the companion book of “historical miniatures”, vivid re-creations of moments in history, among them the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the Battle of Waterloo, go some way to explain both the responses to his work, the fiercely hostile and the admiring. Zweig is a man of letters who reads like a man-of-the world; there are stories set, for instance, in grand hotels and Italian lakeside resorts. He is wonderfully fluent, never at any time difficult. There probably isn’t a single sentence you have to read twice in order to extract its meaning. On the other hand there is scarcely one you feel inclined to read again in order to savour it. (One should say that the translations by Anthea Bell seem excellent.)

He was the kind of writer who now seems extinct, yet for whom many readers may long: the intelligent middlebrow who wrote for an intelligent and cultivated middle-class. There used to be lots of them. English-language contemporaries comparable to Zweig include John Galsworthy, Hugh Walpole, Compton Mackenzie, Francis Brett Young, JB Priestley, Charles Morgan and Somerset Maugham. All were well-read in European literature, all were versatile, writing plays, biographies, and essays as well as novels and short stories. All had high literary aspirations never perhaps quite realized; all were very popular, with sales that writers of similar stature today can only envy. They were all more rewarding than demanding, took readers to places they were happy to visit in their imagination, and created characters in whom they could believe. Even their sad stories – and there are several in this collection – were more agreeable than disturbing.

When I reviewed an earlier Pushkin publication of four stories here a couple of years ago, I suggested that Zweig had much in common with Somerset Maugham. Zweig, I think, lacks Maugham’s gift for comedy, evident in Cakes and Ale, surely one of the finest English novels of the first half of the 20th century, but he does resemble Maugham in his assurance, fluency and ability to charm. Sometimes indeed he sounds like Maugham – in Anthea Bell’s English version anyway: “While you were with him, looking into his bright, kindly eyes – and they were indeed always brimming over with kindness – you couldn’t dislike him. It was only later that you were worn out and wished him at the Devil”.

All the stories, both fiction and factual, in these two collections read easily and agreeably, and have great charm. You are in the company of an accomplished and engaging raconteur with an understanding of the vagaries of the heart and a keen eye for the significant detail. Yet along with the charm, which is itself suspect to severe critics, there is a weakness for platitudes: “Someone who falls off the carriage of fate as it travels along will never catch up with it again.” This is trite, even smug. It’s also untrue, as indeed the revival of Zweig’s own reputation here demonstrates. The Pushkin Press has put him back on that travelling carriage – and deserves our thanks for having done so.