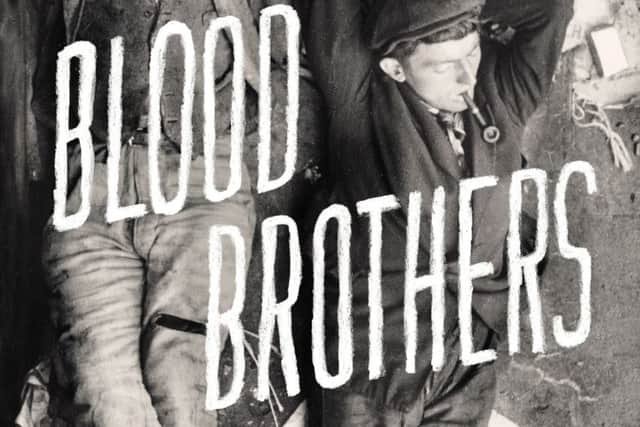

Book review: Blood Brothers by Ernst Haffner

Blood Brothers

By Ernst Haffner, translated by Michael Hoffmann

Harvill Secker, 216pp, £12.99

Blood Brothers” is billed as “A Lost German Classic”. Lost certainly, classic perhaps, remarkable and gripping anyway. Little is known of the author, , except that he was a journalist and social worker. Evidently, both trades or professions gave him the material for this novel of feral youth on the streets of Depression-era Berlin. It was published in 1932 and banned by the Nazis – copies burned too, I would guess – the following year. Its picture of German youth was not one which they wished to promote; it’s a very long way from the fresh-faced blonds of the Hitler Youth marching happily and singing that tomorrow belongs to them. For Haffner’s street-boys, tomorrow doesn’t extend beyond the next meal and glass of beer or schnapps.

For many of us in the English-speaking world the Berlin of 1930-33 has been Christopher Isherwood’s. In a late Isherwood novel, Down There on a Visit, a friend mocks Isherwood as an eternal tourist, sending postcards home. Fair enough; excellent as Mr Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin are, one is always aware that he has a return ticket to home comforts in London in his pocket. Haffner’s boys have tickets to nowhere. They live on the streets, in cellars or in wretched bug-infested lodgings. Politics, even the street politics of the Nazis and the Communists, mean nothing to them; they play no part in the novel. The police are another matter. Several of the boys are runaways from “Reform Institutions”. Without papers they are in danger of being returned to them. Anything – even hunger and bitter cold or, in extremity, prostituting themselves is better than that.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Blood Brothers of the title are a gang with a charismatic leader, Jonny. For a time they are flush, in the money, when he organises pickpocketing expeditions, the boys working in teams of three – echoes here of Oliver Twist, but without the humour. There are few jokes, only solidarity: “Berlin – endless, merciless Berlin – is too much for anyone on their own.” The boys are confined by necessity and inclination to the miserably poor eastern working-class part of the city. Once, when two boys venture further west, they are astonished by the prosperity. The gang has its own sense of honour, each for each is their only principle. They have their own sense of justice, once meting out punishment, after trial, to an informer, in a scene which is harsh, brutal, and horrible to read.

The novel has its two heroes, Ludwig and Willi, both absconders from the Reformatory. At first pleased by the gang’s sudden affluence, they are disturbed by the pickpocketing. In the first place, they can’t believe the Blood Brothers’ luck will hold; the police are sure to catch up with them. More importantly, they disapprove. Purses are being lifted from poor people, mothers and widows who are almost as poor as the boys themselves. It’s not right. So they resolve to get out, make themselves scarce, and go straight, or as straight as is possible for runaways without papers. After a night up West when they are picked up by two elderly men in dinner jackets and given a good meal for services to be rendered – an experience which disgusts them – they embark on a respectable trade, buying used shoes, repairing and polishing them, and selling them on to second-handed dealers. Recognised and informed on, arrested and identified, they are returned to the Reform Institution, but they have nevertheless a future. They will have gone “through every sort of hell and limbo to escape from welfare”, from “the sort of upbringing that claims to guard against moral turpitude”. Haffner’s irony is as savage and indignant as his sympathy is deep. Most of the time he observes and recounts without comment. Comment is indeed unnecessary. The boys’ lives and experiences speak for themselves, speak compellingly.

One wonders, inevitably, what became of these boys after the Nazi takeover when the Party set itself to clear up the streets. Some doubtless would have been consigned to the camps as criminals and moral degenerates. Some would have taken the opportunity to sign up for the New Germany, as one of Klaus Mann’s boyfriends did, telling him that his beliefs didn’t matter; the Nazis were the bosses and it was better to join them. As for Ernst Haffner himself, all record of him disappeared, and his fate is unknown. It may be presumed that he died, somehow, somewhere, in the war.

Michael Hofmann is now the doyen of translators from the German. He is responsible for bringing Hans Fallada to our attention and for new translations of Joseph Roth. There are echoes of some of Roth’s Berlin journalism here, but whereas one is always aware of Roth’ luminous personality in everything he writes, one has only an occasional sense of Haffner himself.

It is as if he really was the camera Isherwood claimed to be. Haffner’s manner is mostly deadpan. This is how it is on the streets, he says. Actually, the novel this invites comparison with is I Ragazzi, Pasolini’s vivid picture of street boys struggling for survival in the miserable poverty of post-war Rome. But there is at least sunshine there. There is no sunshine, only bitter cold, in Haffner’s inferno of “merciless Berlin”.

This is an astonishing novel, every bit as astonishing in a different way as Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, and deserves to have the same success.