Book review: All That Is by James Salter

All That Is

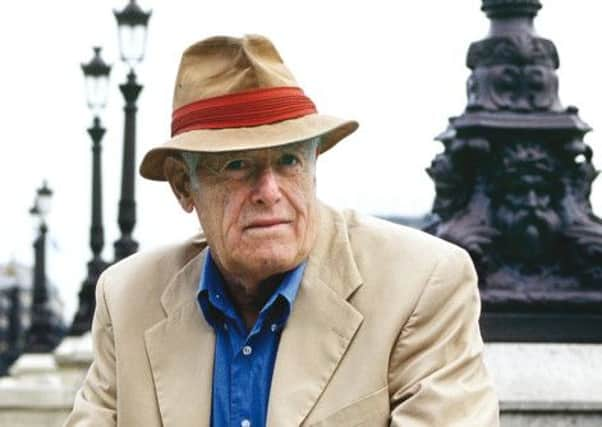

James Salter

Picador, £18.99

Or politely hidden from view, through the very same motivation?

This quandary arises in the course of James Salter’s All That Is, which takes place partly in the world of publishing – but that’s not the only reason I raise it. In the book, an elderly writer “still respected for an early book or two” has submitted something “done elegantly enough but past its time”; our protagonist, Philip Bowman, visits him to break the news that the book hasn’t been accepted, only to like the old man enough to publish after all.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn real life, James Salter, much-lauded for an early book or several, is now 87; this is his first new novel since 1979, and who knows what he did to charm his publishers, but sporadic elegance certainly doesn’t disguise it being past its time, if indeed it ever had one.

The book commences with Bowman and his army buddies aboard a ship bound for Japan, deep into the Second World War. “It was a day Bowman would never forget,” writes Salter. “Neither would any of them.” He hereby sets up two defining characteristics of the ensuing loose collage of their later life experiences: a mournfully elegiac tone, and a loyal dependence on trite, pseudo-profound phrase-making.

Salter is much praised as a stylist; indeed, fellow novelist Richard Ford argued in 2007 that he’s treated as suspect because his work is too perfect. “There are no splinters in Salter’s sentences,” Ford claimed. Perhaps – but there are certainly some oddly used words, and commas, and tenses. The following examples are typical, both in icky content and befuddling form:

“In her well-fitting riding clothes he imagined her as a few years older with certain unfatherly thoughts though he was not her father, only a good friend.” (Huh?)

“What is there about a woman who had fallen in love and gotten married and now stands before you in almost foolish friendliness, as a supplicant really, in high heels, alone and without a man?” (Huh?)

“Her buttocks were glorious, it was like being in a bakery, and when she cried out it was like a dying woman, one that had crawled to a shrine.” (And when I cried out, it was like a laughing woman, one that had read something absolutely ludicrous.)

Advertisement

Hide AdBowman’s unquenchable horniness and corresponding dismissiveness of women as people are constants, and shared with other male characters in the book. Of course, characters aren’t always direct channels for the attitudes of their author, and a book about sexism is easily confused with a sexist book. But there’s little room for that sort of theoretical manoeuvre here.

Suggesting a marked ignorance of just which gender tends to buy and read literary novels about marriages and other intimate relationships, Salter’s narrator assumes throughout a male reader, noting in low, mean asides the disappointing or threatening behaviour for which “you” may rely on women: “The truth is, with some women you are never sure…” “He didn’t like women who looked down on you for whatever reason…” “All powerful women cause anxiety…” My God, Mr Salter, quite a number of us out here actually are women! We can read! And we do not see ourselves as some sort of inexplicable, malign other.

Advertisement

Hide AdThis feels like a bias in the writer, not just his character – as is the instinct to assess every female passing through the narrative in terms of her sexual viability; to describe one as “like a wind-up doll, a little doll that also did sex”, or grudgingly acknowledge one for being “the age when she could still be naked”; in general to recognise almost no function for them, from childhood onwards, but as sex objects, or potential ones. The age at which nudity remains permissible, incidentally, is apparently ephemeral for women but indefinitely enduring for men. And a woman or girl’s suitability as an object for sexual use is not conditional upon interest or consent at her end: indeed, Bowman actively prefers having sex with his numerous conquests when they are either resisting him, or still asleep.

One of his girlfriends has a teenage daughter, a schoolgirl when he meets her; as soon she’s introduced, you know that she’s going to end up in his bed, since Salter wouldn’t bother spending time on her otherwise, and so it tediously transpires.

Another little girl doesn’t even have to clear puberty to be described in terms of her “seductive” skin colour (she’s half-Sudanese; it would have been prudent of Salter’s editor to have addressed, before publication, some of the ways in which he refers to black women through the book).

There are some atmospheric bits of writing. Yes. If you really want to imagine being a soulless narcissist who drifts around wondering if nearby women are worth quasi-raping, Salter will serve you with some evocative paragraphs. More often, though, this book is as unfocused and pretentious in its style as it is grossly unevolved in its thinking. «

Twitter: @HannahJMcGill