Arts review: VAS:T 2015, Royal Scottish Academy

VAS:T 2015

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

*****

VAS, or Visual Arts Scotland (long ago in an earlier incarnation it was the Scottish Women Artists) is the last of the three exhibiting societies to present its annual show in the Royal Scottish Academy this year. Sharing the rather mean time slot made available by the National Galleries of Scotland, each of the shows has lasted just three weeks. If it is so short because the societies can’t afford more time, then the rent’s too high. At least they have had the luxury of the whole space, however, and that has been telling with the VAS, perhaps even more than with the others, for it includes a much wider range of work. It is the main forum for the skilled and inventive craftsmen and women who are such an important part of our cultural landscape yet who get very little look in when it comes to the major shows otherwise.

Exhibits include work by members, work selected from an open submission, invited artists and recent graduates. They range from painting, print-making and film, through tapestry, glass and ceramics to jewellery and furniture. There is even a full-sized sailing dinghy with its sail up, Lost at Sea. Beautifully made by Thomas Hawson, I was assured it is seaworthy and will be launched in due course.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are beautiful objects all around. Keiko Mukaide’s Unopened Letter from My Mother, for instance, is a set of heavy, richly coloured lumps of glass. They seem to exist only to please the eye and hand, and that is surely refreshing when art so often strains to do anything but. A silver dish by Aoife White with gold inside and a sculpted lid with a serpent’s tail for a handle has the same quality. It is simply a covetable object. So are Bryony Knox’s silver bird jugs.

There is also a wall of small objects by members of the society, called Wall of Jewels. Some are actual jewels, most are jewel-like. That could suggest this is all a bit lightweight, but it is not. It is simply that sensitivity to materials, and care and delicacy in their treatment, run through the show giving it a really distinctive quality. It is a relief to see people taking a delight in what they do rather than earnestly trying to make art without actually making anything lest they should commit the solecism of accidentally producing something useful or beautiful.

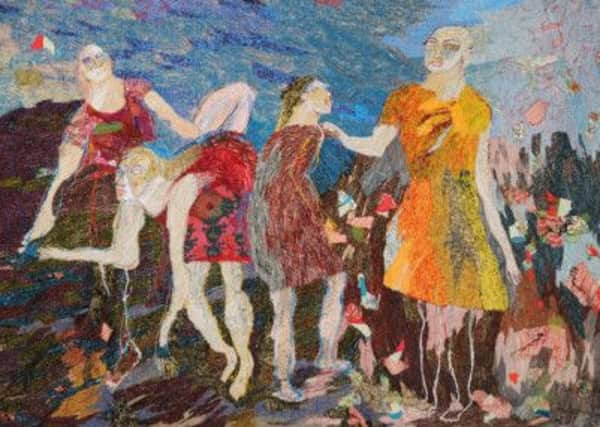

Nor is it all small-scale and pretty here. Invited artist Alice Kettle has three very large panels. Needlework rather than tapestry, they are rich in texture and colour. Two of them, Pause and Pause II, are based on Poussin’s A Dance to the Music of Time, with the artist with her mother and sisters dancing to that music in one, and the artist as mother with her daughters in the other. The third and largest panel is magnificent. It commemorates Loukanikos, the dog who joined the protesters confronting the riot police in Athens. Poor dog, his health undermined by too much teargas and police kicking, he died last year, but here he has a fitting memorial. All three panels are vivid and beautiful. Though modern in style and execution, they nevertheless call to mind Phoebe Traquair’s wonderful needlework panels from a century ago.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS

These three works also set the scene for a group of tapestries that make a show within a show. These are the eight shortlisted artists for the Cordis Tapestry Prize, a £5,000 prize for an experienced weaver. It is a sign of vigour that there were 53 entries to produce this shortlist. I particularly liked Unn Sonju’s Blood Cannot Be Washed Out With Blood, which carries those words in a wall of flame. Sara Brennan’s Hill Forest is a simple landscape of a white hillside leading up to a dark line of trees. More straightforward, it is nevertheless eloquent. So too is Pat Taylor’s Artemis, an enigmatic blue head gazing out. When the image is so simple, you really do read it as weaving – invoking the classical goddess is a reminder both of how ancient weaving is and how from pre-history it was associated with women, the distaff side. Anne Jackson touches on a more sinister side of the same tradition in the Great European Witch-Hunt, where she renders the word for witch in ten different languages.

There are also other textiles in the show. Lisa Green’s Conspicuous by Absence is a set of garments reduced to a ghostly skeleton of thread and paper as though eroded by time. Hanging like washing on a line, the effect is strangely wistful. Adil Iqbal’s Life in the Outer Hebrides is a needlework panel, more modest than Alice Kettle’s, but with undoubted charm.

There is some fine furniture, though it undermines confidence a little to admire a handsome chair, but be warned by a prominent notice “Do not sit”. Among some striking ceramics, but in fact made out of latex, Tessa Clowney’s Rhythms in White is a Morandi still life in three dimensions. Andrea Walsh’s Four Cups, four minimal cups in blue, white and gold, is likewise much more a still life than a collection of elegant crockery. Ellen McCann’s Unfurl is a ceramic sculpture that describes in three pieces the progressive opening of the leaves of a flowering bulb. Kevin Dagg’s Fine Balance is a two-part sculpture that seems to make a point about religion. In one a very small head supports a very large mitre. In the other a monk supports a plump Buddha.

Advertisement

Hide AdPaintings include Joyce Gunn Cairns’s tender and beautiful Absence, two women supporting each other watched by a robin, with thoughts of absence pencilled behind them. Jeff Zimmer’s misty landscape, We Were All Wrong (The Myth of the Hero), is in effect a painting, but with glass and light as the medium. Mark I’Anson’s Oh What a Lovely War (With God on Our Side) is a set of anonymous portraits from the First World War executed with great delicacy and limited colour, somewhere between painting and drawing.

There are several films. The most substantial is invited artist Rachel Maclean’s The Weepers, a dark vision of Scotland as a kind of dystopian Brigadoon.

Advertisement

Hide AdJane Hyslop, who makes books, is another invited artist. Her display of beautiful botanical drawings, garden plans and historical linen patterns is notionally linked to the origins of the RSA, the National Gallery and Edinburgh College of Art in the Board of Trustees for Manufacture and their establishment 250 years ago of a school of design, ancestor of the ECA, whose primary objective was to improve the quality of Scotland’s linen manufacturing.

With more than 300 artists showing, there is much more too. There are even living artists on view. While I was there, Susie Leiper, master calligrapher, was working on a large inscription on the subject of maps: a joint piece with Lucilla Sim, The Map is Not the Territory.

Sitting working at his desk, Hans Clausen, meanwhile, is his own artwork and will be throughout the show. Occasionally he changes places with visitors, however, so that they in turn become both artwork and artist.

This show marks the difference between the VAS and the two societies that have preceded it, but all three are to be valued. Together they have given a shop window to a thousand artists and have brought their varied work to us – most of it good, some of it outstanding, but which we might never have had a chance to see otherwise.

Taking the whole gallery for each exhibition has paid off in the striking quality of the presentations, but each show represents an enormous collective effort by the members of the societies. They deserve more than three weeks.

• Until February 28