Arts review: Tony Swain, Glasgow

Tony Swain: The Shorter Alphabet

Modern Institute, Aird’s Lane, Glasgow

****

These days the printed page has the opposite connotations: analogue, physical and reassuringly tactile, a place for slower contemplation. It’s this odd middle ground between the quotidian and the obsolete that has made print, and newsprint in particular, such a fertile ground for artists of late. At the Edinburgh Art Festival, for example the duo kennardphillips have shown artworks made on rolls of unused surplus newsprint. For others, the newspaper format is a brilliant way to make inexpensive and accessible publications, like Panel’s recent paper for their Tramway exhibition The Persistence of Type.

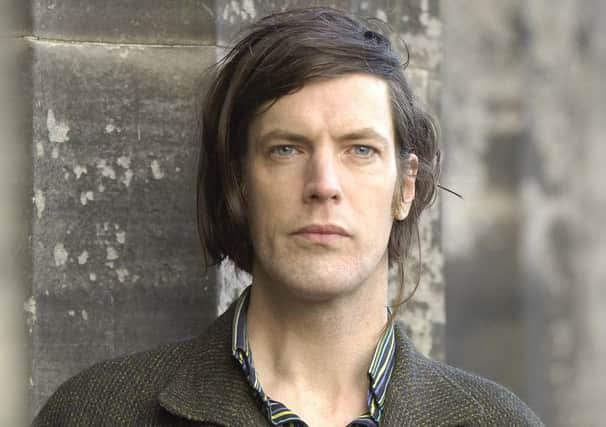

The artist and musician Tony Swain is in his late forties and therefore old enough to remember the days before digital. But his choice to make paintings on newsprint is less luddite than lyrical. The text and images of newspapers open up a set of prompts, both visual and intellectual, for the creation of new works that still have their roots in the chance encounter of the daily news.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis work perhaps belongs to an older tradition of newspapers in art. Like a host of painters before him, from Braque and Picasso to Willem de Kooning, Swain has found that reaching for the abandoned newspaper on the studio floor has turned out to be a fruitful way of considering painting’s relationship with the printed image and the lived world, the messy contingency of the everyday and the unstoppable daily flow of information.

Swain was born in County Antrim and has long made his home in Glasgow after studying at Glasgow School of Art. He represented Scotland at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and works on what he describes as “pieced newspaper”. Largely that means working on yesterday’s news, pasting the sheets together to make a large ground for over-painting in acrylic. Evoking the skewed landscapes of artists like Paul Nash and the claustrophobic urbanism of writers such as JG Ballard, Swain’s work has used the images found in newspapers to extend the boundaries. He creates fictional worlds by loose-limbed paint on existing newspaper images, altering them by extending, repeating and obscuring the original print. Those boundaries include size too. While his artwork relies to an extent on the compact dimensions of a newspaper page, the practice of piecing them together creates a format more often associated with the scale of oil on canvas. His 2007 painting Jesus Help Me Find my Property, which is owned by the Tate, is a mind-bogglingly delicate work more than 3m in length.

Swain’s new show at the Modern Institute’s Aird’s Lane premises lives up to the implications of its title, however. In his recent exhibition at Baltic, Swain punctuated the large-scale showstoppers with smaller meditations.

In Glasgow, contrasting with the industrial height and feel of the building, Swain is showing 11 new works which are small in scale and in which he is developing more intense and spontaneous ways of working with print.

Although it is easy to describe his paintings as collages, that has rarely been the technical case. In this show, however, a number of works show clearer examples where paper has been torn and overlaid, or folded and rippled.

Where once Swain’s art opened up new imaginative horizons, these works seem to focus more on the hallucinatory possibilities of intimate spaces and ideas: domestic interiors, half-obscured portraits and fleshy abstracts. The largest work in the show, Have felt half filled, is just 48cm x 64cm. It shows an old-fashioned domestic interior, with a standard lamp and an embroidered lampshade. A figure in the foreground is part painted out, suggesting a half-glimpsed or half-remembered presence. On what may have been the facing page of the original paper, we can make out the image of a wooden chair, but it is unsteady. It has been doubled or mirrored in paint. On a smaller scale still are lovely, insouciant works like Sanity at the open window, an abstract of almost floral abundance in Klein blue, and the thick, flesh-coloured pinks of Rhyme delayed.

Advertisement

Hide AdNewsprint has a strange relationship with permanency. Robust enough to be consulted decades later in your local library, it is nonetheless an archivist’s nightmare. Designed to be cheap and expendable it is inherently unstable, prone to yellowing and tending to brittleness. The best of Swain’s works suggest this process of ongoing change.

Created through improvisation rather than rigorous planning, these claustrophobic new paintings are never quite fixed; like the world the newspaper represents back to us, they are on constantly shifting ground.

Until 22 August.