Arts review: RSA New Contemporaries, Edinburgh

RSA New Contemporaries

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

* * * *

The work in the RSA New Contemporaries exhibition is selected from the degree shows of the five Scottish art schools by a small team from the RSA. This year, led by Francis Convery, they have put together a very good show. The work is lively and seems full of promise. Each artist is given enough space to put up quite a substantial little exhibition, but it isn’t crowded. The colleges are represented on a ratio of one in seven of the graduating class of each of them. Thus Moray College, the smallest with just 14 graduates, has two in the show. Glasgow, the largest with a graduating class of 128, has 18. Edinburgh and Dundee both have 14 and Gray’s School in Aberdeen has eight. Nevertheless, this is primarily a showcase for the artists, not the art schools. Although the catalogue lists them by school, you are not reminded of their individual affiliation when looking at their work.

As you go in, Linda Cook’s Still Small Voice greets you at the top of the stairs. It is a slightly dizzying wall of spinning, coloured disks. Spinning they are each one colour, but as you approach, as though conscious of your presence, the disks nearest you stop spinning to reveal they are watercolours composed of radiating bands of colour. It is a nice idea: the private life of art. When you are not there, maybe all the pictures in all the galleries everywhere come to life like this.

Advertisement

Hide AdHere as you go on into the galleries one of the most striking things is by Harriet Yarrington, an installation of clothes, gloves, books, bits of fabric, drawings, sewing materials and bric-a-brac. All things you might find at home, they suggest personal associations, but then you discover that not only the drawings, but some of the most delicate objects are also art works, not found objects. This has been done so often before it is usually of little interest, but by the care she has taken, the artist has managed to endow it with real poetry.

Nearby, David Sampeti does actually write poetry. He also recites it. His wall of small framed paintings each accompanied by a short text in poetry or prose is further animated by his voice and by music. It is a nice attempt to achieve the classic ambition of synesthesia, the union of all the arts. When I read what he says about it, however – “underlying my practice is an inexhaustible, almost pathological love of images. In my work images operate as a synthesising force for my personal cosmology” – I wonder if the work would not be better without such a confession. In the same room William Darrell has created towers out of silver, flexible duct piping and green heads of broccoli. In a film he blows a home-made tuba constructed from similar materials. Its lugubrious moaning drifts around the galleries. It all arises, he says, from “a blurring of reality and Hollywood fantasies”. It is quite daft, but rather charming.

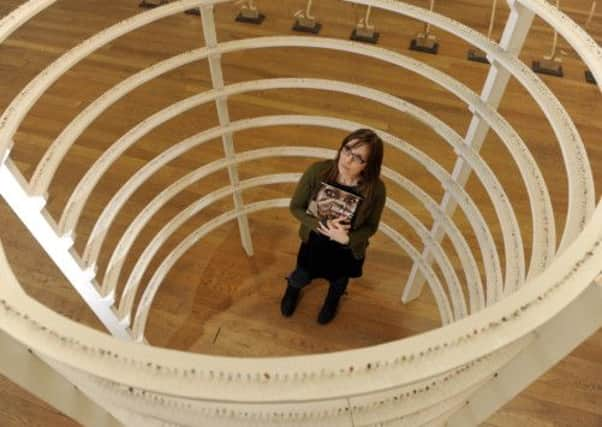

Sally Webber has a series of pictures, each one a homage to a different historic figure: a blue square for Josef Albers; a cut-out paperback of Allan Hollinghurst’s novel, The Line of Beauty, for Hogarth; mysteriously three bottle tops for David Hume; a page of music gone haywire for Bach and so on. They are summarised at the end in a poem which incidentally also explains the bottle tops – For David Hume / And his missing shade of blue / Three phenomenal tops / From Irn Bru. Among the works in the main gallery, an imposing array of elegant wooden ribs by Caroline Inkle proposes an elaborate pun on the analogy between the ribs of a clinker-built boat and the same element of human anatomy. Ruaraidh Allen captures ambient noise in one huge dish and replays it in another. When the gallery was quiet, you could hear the distant moaning of William Darrell’s home-made tuba recycled. Emma Reid is altogether more intimate, with tiny spy-holes in a box, which replay various things including the image of nearby feet. One of her spy-holes is also set, inconspicuously, into the floor of the next gallery.

Nicola Brennan takes a fierce swipe at the church in her native Ireland and its attitude to sex with a video of a priest, two black pews and a box of spiritual contraceptives labelled “Extra Virgin, Made with blessed latex, 99.9 per cent effective against mortal sin.” Laura Duncan takes a more secular approach to a similar theme. She has taken Gustave Courbet’s once scandalous painting of a vulva, L’Origine du Monde, shaved it and added a vajazzle. I confess had never encountered the word before, but the Oxford Dictionary defines it – as a verb, however, not as a noun – “to adorn the pubic area (of a woman) with crystals, glitter, or other decoration.” In case you missed Courbet’s point, here the glitter spells the word “enter” with an arrow pointing in the desired direction.

Hayley Fisher also amends 19th-century art rather effectively with a set of prints that add modern nudes to Gustave Doré’s illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Theresa Moerman Ib has filled glass cases in the Academy Library with small, whimsical objects. Old Stories Spun Anew is a set of balls of string or knitting materials made from hand-spun audio and VHS tapes. A pile of Home-Sickness bags has printed on them instructions for use.

One phenomenon in contemporary students’ work is a frequent, fierce engagement with process. It is admirable in its conviction, but doesn’t always lead beyond itself. Miriam Mallalieu, for instance, arranges countless fragments of paper on pins. Though she writes about it very clearly, in the work itself she seems to confuse an almost obsessive process with its product, but without product the process is inscrutable.

Advertisement

Hide AdJustine King is one of several who use drawing this way. She covers sheets of paper with endlessly intricate drawing which seems to have no meaning beyond the action of doing it. When she adds glitter the result is rather beautiful, however.

The most remarkable exponent of this approach is Naomi Ojima, showing downstairs, with a drawing ten metres long made from endless hatchings in blue ballpoint pen. It is beautiful, too, if also a bit baffling, but perhaps we should welcome this kind of thing as reflecting the rediscovery of drawing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlso downstairs, Flora Debechi makes charcoal and then draws with it; her means is her end; process is literally product, but she does also display the wonderful qualities of charcoal as a medium in a tall abstract drawing. Rachel Grant has done a similar drawing with pure blue. She used threads stretched between nails to flick pigment in radiating lines across a sheet of paper. It was done as a performance apparently; product actually collapsed into process.

Among the best things in the show are Ibrahim Adesina’s prints. Strongly composed, they are what used to be called capriccios, disparate monuments and scenes brought together in a single composition. In one picture a red grouse, ostriches, elephants and rhinos appear with Dunnottar Castle. In another a gorilla looks out across an African scene towards Manhattan.

The best single work in the show however is by Amy Gear. A huge disc of pure black handmade paper half covering a similar white disk; the moon moving across the sun in an eclipse.

Each student has to write a statement. Some are quite good, but some are awful, full of pretentious, impenetrable artspeak. Artists have to write these things all the time, but artspeak is a pernicious infection. It rots the brain of art. Perhaps you can inoculate against it? Maybe setting up a prize for the clearest and most jargon-free statement by a student in this annual show would be a start?

• Until 8 May