Arts review: Lunde | Susie Leiper | Kate Downie

Rocks & Rivers: master-pieces of landscape painting from the Lunde Collection

***

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

Susie Leiper: The Living Mountain

****

Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

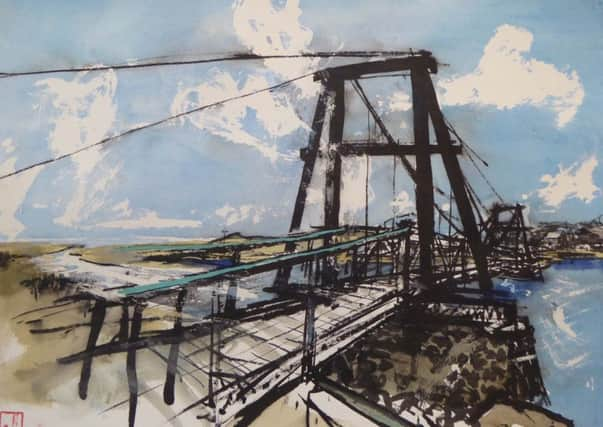

Kate Downie: Estuary

****

Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

Our nearest neighbours lie undoubtedly to the south, but that becomes less and less true the further north you go. Then, increasingly, Norway and Denmark, our neighbours to the east, get closer. Indeed, if London is your destination, Norway is almost as close even to Edinburgh. Historically this proximity was reflected in many ways, not least in artistic exchanges. Bergen Castle was built by Scottish masons in the 16th century, for instance, and Stavanger Cathedral decorated by a Scottish sculptor, Anders Smith, in the 17th, but then these links lapsed. As national schools evolved in Scandinavia, preoccupied by France we overlooked the art of our nearest neighbours. It would seem likely to have a close affinity to our own, but is scarcely represented in our collections, if at all. Recognising this, the National Gallery has organised a loan from the collection of Asbjörn Lunde, an American of Norwegian descent, that includes a small group of Norwegian paintings.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are a dozen paintings in this loan, half are by pioneer Norwegian painters Johan Christian Dahl and Thomas Fearnley and the other half by Swiss painters Giuseppe Camino and Alexandre Calame. What they have in common is that they paint mountains. The Swiss painters, too, are unfamiliar, but their landscape, being en route to Italy, never was. It was painted by Brueghel in the 16th century, by John Robert Cozens in the 18th and incomparably by Turner in the 19th.

You can’t say that of Norway. Dahl was really the first to paint his native country. Fearnley – Norwegian, but whose family came from Hull – was his pupil. Dahl studied in Dresden where he was a close friend of Caspar David Friedrich, and when he paints a shipwreck on a wild northern coast that link is clear. Nevertheless, although Friedrich captured the wild poetry of the north, he was rarely specific about place. For Dahl, on the other hand, topography was what mattered. He made long and difficult journeys to paint Skjolden, for instance, a tiny settlement at the head of Norway’s longest fiord, or to climb mountains deep in the Norwegian interior where he painted a massive hanging rock. This latter picture too is dated to the day, 27 August,1850, so it not only records a specific scene, but also how it looked at a specific time. Both pictures are freely painted, too, and so are quite unlike anything Freidrich might have done. A study of a tree hanging over a rock by Thomas Fearnley is likewise dated to the day, 11 July, 1839, and vividly conveys the impression of the artist’s spontaneous response to an actual scene.

These pictures suggest that if we ignored what the Scandinavians were doing, the opposite was not true. English landscape painting, especially with Constable, was intimately concerned with time and place. Thomas Fearnley travelled in England and indeed one of his paintings here is of Derwent Water, made fashionable by Wordsworth and the Lakeland poets. It is not Wordsworth who you find echoed in these evolving European national schools, however, it is Walter Scott. Go to almost any national gallery where, unlike our own, the national school is the main object of interest and I guarantee you will find somewhere near the beginning of the story a painting that records a pilgrimage to Abbotsford. Scott did not invent the idea that there was a fundamental relationship between a nation’s self-consciousness and the landscape that is its home, it had been hammered out by the painters and poets who came before him –but he gave it universal currency. It had, however, also been articulated as an aesthetic theory by his contemporary, Archibald Alison. A now forgotten, but once very influential Enlightenment philosopher, he was one of the first to try to construct an empirical aesthetic: one that did not start from a notion of ideal beauty, but from an analysis of what we actually find beautiful. He based his theory on landscape and argued out that even the wildest places can appear beautiful to us because of the associations they hold: thus the Highlands and their wild mountains became the national landscape of Scotland.

That being so, it is a pity these Norwegian paintings have been paired in this display, not with Scottish pictures from the national collection, but with ones by pre-Impressionist French landscape painters. With the brilliant exception of the Anglo-French Bonington, the comparison, indeed the contrast, underlines how old-fashioned the French still seem to be, how Poussin was still their model. Nevertheless it misses out on what might have been an interesting story.

Alison’s aesthetic still has its followers, though they are certainly unconscious of their debt, and our painters still paint mountains. At the Open Eye, Susie Leiper has dedicated her exhibition, The Living Mountain, to Nan Shepherd and her celebration of the Cairngorms in her short, poetic book of the same name. For Alison, himself a divine, the ultimate association of landscape was the Creator, an idea given monumental expression by Constable in his great painting of Salisbury Cathedral. Nan Shepherd doesn’t write about God, but she certainly finds a deep spirituality in the mountains that Alison might have recognised. Thus she does not write about going up, or even onto a mountain, but about going into it, entering into and so sharing its immanence. In her approach, summits are a distraction. Munro bagging would be an irrelevance, an impiety. Susie Lieper talks the same way. Her pictures, she says, come from “looking into the mountain” and so they are not conventional views, but abstractions.

She does name her mountains, however. Translating their Gaelic names into English, she brings out how descriptive they are, how our ancestors painted with words. But there are no summits here, only evocations of what it is like to be in the mountain surrounded by mist and rocks, by the immediate and the vastly distant. She paints in oil on unprimed canvas, or in watercolour on stretched, unsized paper. Mostly she uses blues and greys and the white of paper or canvas, but occasionally brings in the startling, brilliant orange of lichen and moss.

Advertisement

Hide AdDepth and distance are there in her absorbent surfaces, but sometimes too she suggests a shift from near to far by changes of texture. These are indeed paintings that work by association. Leiper is best known as a calligrapher and in that skill has learnt much from oriental models. There is hardly any calligraphy here, but there are clear echoes of classical Chinese landscape painting where distance is often a function of misty transparency, or simply of the emptiness of an unpainted surface.

Kate Downie who is showing at the Scottish Gallery has also turned to oriental models. Indeed, she has travelled and painted in China, but in her new work it is not so much the misty depths of Chinese painting as the fluency and precision of oriental brush painting and calligraphy that seem to have inspired her. Her show is called Estuary and, as official painter for the Forth Road Bridge’s 50th anniversary, she has paid tribute to the structure by bringing together paintings of other bridges and other estuaries in China, Japan, Australia and indeed the Thames.

Advertisement

Hide AdSubjects include Sydney Harbour Bridge and the ancient wooden arched Kintai Bridge in Japan, echoing the woodcuts of similar bridges by Hokusai and Hiroshige. Oriental models like these have brought a new clarity to her work and an appreciation of the pictorial value of emptiness. This is very appealing when she combines it with fluid brush drawing as she does in Hunter’s Point Sydney, for instance. Trees described as though with a single stroke of the brush cross the composition in the foreground to define the distance beyond with beautiful economy.

• Rocks and Rivers until 30 April 2017; Susie Leiper until 22 April; Kate Downie until 28 April

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS