Arts review: 20th Century Masterpieces, SNGMA

20th Century: Masterpieces of Scottish and European Art

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

****

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art was founded 55 years ago. Now “following the huge success of Generation” the top floor has been rehung to mark that anniversary with “masterpieces from its impressive permanent collection.” The subtext of this is perhaps a reminder to the long-suffering public whose gallery this is, that after it has been filled for so long with such very large works of art that say so very little, we do have a collection of real art worth looking at.

The principle of “Modernity” on which the collection was founded was that the art of the 20th century, and so now of the 21st, is different from anything that went before it and so needs its own institution. That idea may have been liberating at first, but it is really pretty questionable and has also been self-fulfilling. Artists, convinced by their century’s claim to be exceptional, were led down some pretty barren pathways. Institutionalising it all with an arbitrary start date of 1900 was always dubious, but we are stuck with it, although there is at least a feeling now that perhaps the boundaries between the NGS’s three institutions should be more porous.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn 1960, the beginnings of the SNGMA were modest. In Inverleith House it had little space and less collection. Twenty years later it moved to its present home, the former John Watson’s School. Then Thomas Hamilton’s magnificent Dean Orphanage was added to create the campus on Belford Road, now hopefully christened Modern One and Modern Two. Over the years, the collection has grown steadily by purchase, gift and bequest, but it was most dramatically enlarged by the acquisition of the Gabrielle Keiller and Penrose collections. Its foundation, however, was Sir Alexander Maitland’s collection which came both by gift and bequest in 1960 and ’61. A good many of our true modern masterpieces came from him. The present display, for instance, includes his lovely Bonnard, Echappée sur la Rivière, his solemn and imposing Rouault, Head, and also a less familiar but beautiful still life by William Nicholson that did not arrive in the collection until much later. Quixotically though, Maitland’s star and a true masterpiece, Matisse’s La Leçon de Peinture, is not in the present display. In fact if these are meant to be our masterpieces, several others are missing too. There are rooms devoted both to cubism and to abstraction, for instance, but neither Braque’s le Bougeoir, the only real cubist painting in the collection, nor the gallery’s only Mondrian, Composition with Double Line and Yellow, are here. It does seem odd to have Ben Nicholson’s lovely abstract Painting 1937 with its obvious reference to Mondrian pointed out in the label, but no Mondrian to make the comparison. Perhaps as the collection is brought out so rarely there was a feeling that less familiar works should get an airing, but if so, is this the display of masterpieces it claims to be? In fact, constraints of budget and necessary reliance on private bequests have meant that a good many of the works in the collection, and correspondingly among those on view here, are domestic in scale and aspiration, rather than true gallery masterpieces.

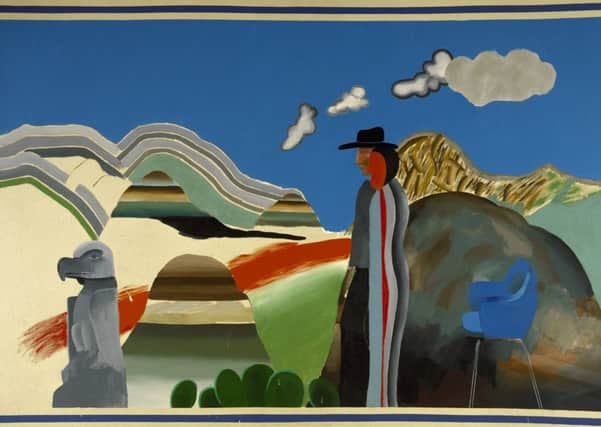

There certainly are a few masterpieces, however. In a welcome departure from the norm, the Scottish pictures are mixed in with everything else. JD Fergusson’s La Terrasse, Café d’Harcourt, and Cadell’s The Model shine as stars, although they are hung alongside pictures by Soutine, Kokoschka and other very different artists. Both Fergusson’s picture and Kokoschka’s Hitler-defying, Self-Portrait as a Degenerate Artist are loans, however. The collection would be much poorer without them. James Cowie’s enigmatic Portrait Group also more than holds its own against paintings by William McCance, William Roberts, Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Christopher Wood and other notables of the 1930s. Oddly, Gillies is not here, however, though both Ben Nicholson’s naive landscape, Walton Wood Cottage, and Christopher Wood’s Building the Boat, Tréboul have a close bearing on his art. Paul Nash’s Vernal Equinox is one of the gallery’s finest paintings from this time, but it too is absent. On the other hand, Stanley Cursiter’s 1913 Futurist style painting, Regatta, is no masterpiece. Never more than a jeu d’esprit much like the Edinburgh College of Art Student Revel, the annual student party, whose decorations that year were on a Futurist theme, it certainly looks a fraud beside Lyonel Feininger’s beautiful Gelmeroda III from the same year. A blue-tinted, dreamy view of a village with a tall church spire, it is a genuine masterpiece.

The gallery’s own painting by Picasso, Les Soles, is an odd picture, more interesting for presenting two of the women in his life as fish on a plate than for its quality. His Seated Nude, however, painted when he was nearly 90, is a ferocious masterpiece. (It is, however, another great painting on loan and so may one day vanish from the walls.) Nearby Germaine Richier’s young man running, Le Coureur, seems to be hurrying to enjoy the unambiguous invitation offered by Picasso’s lady. Elsewhere the hang makes other connections, too, between Leon Kossoff’s Portrait of Father and John Bellany’s My Father, painted ten years earlier, for instance. Bellany wins hands down from the comparison. There is also an intriguing conjunction between Paolozzi’s bronze St Sebastian from 1957 and Joan Eardley’s Sleeping Nude painted two years earlier hung behind it. Paolozzi also appears later on under the heading Pop Art with his grand science fiction sculpture Four Towers. His contemporary William Turnbull, who died last year, has a whole gallery to himself: with paintings, sculpture and drawings, it makes a very impressive display. However, it also makes one realise that Alan Davie is absent. With Paolozzi and Turnbull, Davie (who also died last year) was the third in the trio of Scottish post-war greats. A fourth, perhaps, and certainly their contemporary, Ian Hamilton Finlay, is absent too. This may be because, although it holds an extensive collection of his printed work, the gallery holds no masterpiece by him. Under the heading of Post-Modernism, Steven Campbell’s Elegant Gestures of the Drowned After Max Ernst far outshines the company it is in, even though this includes Georg Baselitz and Sandro Chia.

Meanwhile the collection keeps growing. Three lovely early paintings of Venice by Cadell have recently been presented in memory of Sir Patrick Ford, who paid for the artist’s trip to the city. Two bronzes by William Turnbull have been bought with money bequeathed by Henry and Sula Walton, while 23 works on paper have been gifted by the artist’s family.

The gallery of modern art as it was first proposed by Stanley Cursiter just before the war was to be a powerhouse for modern art in Scotland. It has never quite worked out like that. Until recently its active engagement with living art in this country was quite limited. That policy has now changed, but following that change, it has been almost exclusively preoccupied with one group of artists, those we saw in Generation. If it had followed Cursiter’s vision, over the years the gallery would have had a role endorsing our major artists by buying their work. It would have led the market, creating confidence in modern art in Scotland as MOMA did in New York. That has never happened and a whole generation has been missed out. The late John Houston, for instance, acutely felt the slight that his work was not properly represented in the national collection. There are other major artists – a whole generation, indeed – who would be justified in feeling the same. Duncan Shanks, Philip Reeves and Frances Walker, to name but three, all came of age around the time the gallery was founded in 1960, but they are scarcely represented its collection, if at all. That is not right.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS