Edinburgh Art Festival reviews: Christine Borland | Christian Newby | Sekai Machache | Alberta Whittle

Christine Borland: In Relation to Linum, Climate House, Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh *****

Christian Newby: Boredom>Mischief>Fantasy>Radicalism>Fantasy, Collective, Edinburgh ***

Sekai Machache: The Divine Sky, Stills, Edinburgh ****

Alberta Whittle, Jupiter Artland ****

Advertisement

Hide AdFlax was grown in Edinburgh’s Physic Garden, the precursor to today’s Botanics, as far back as 1670, and Christine Borland’s project, In Relation to Linum, was intended to mark the Gardens’ 350th anniversary in 2020 as well as the reopening of Inverleith House as Climate House. Thanks to the pandemic, she has had another year to think and work, and this delicate, poised exhibition seems to bear witness to that time.

A wealth of information about the social, economic and botanical history of flax lies behind this show, but Borland knows better than to foreground it. What she foregrounds is process. Having learned the processes around growing, harvesting and drying it (spinning and weaving are still to come), she grew a crop herself during lockdown with the help of an online community of other growers. The works in this show, beautifully displayed in the Georgian rooms of Climate House, explore these processes in words, in delicate watercolours on flax paper, and in displays of samples which are part museology, part art.

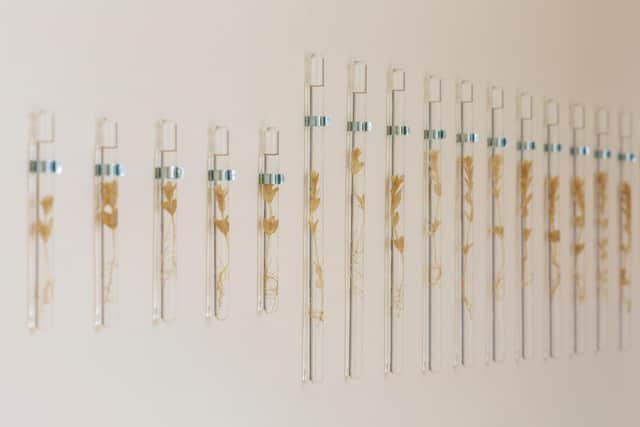

There are dried and pressed samples, made according to RBGE guidelines, creating letter-like forms on the walls like a flax secret code; a collection of specimens preserved in alcohol, one from each day of the plant’s 100-day growth cycle; plaster specimens of the leaves of the much larger New Zealand flax (not related to linum).

In the last of the upstairs rooms, there are two wall-based sculptures, bunches of flax like long pony tails arranged geometrically in clay vessels, and wispy offcuts which map freeform patterns around clay cones. Alongside these is a further series of watercolours in which the female flax grower seems almost to dance with her bundle of fibres. They reference the processes but transform them, making them mysterious and beautiful.

In the final room of the show is a digital work which recreates the tasks of the flax grower using CGI technology, as if storing these ancient processes for a future community which might one day need to rediscover them. It’s a new departure for Borland, and a stark change of aesthetic for a show which has been about the natural and the hand-made. While this step-change is not entirely comfortable, it’s clear that the same attention to detail and delicacy of touch have been invested in the sparkling, seed-like pixels on the screens.

It would be unfair to judge Christian Newby against the subtlety and precision of Borland’s work. He uses textiles, too, but his process – using a hand-held carpet-tufting gun – employs both natural materials and man-made ones, such as plastic twine. His new work, Flower-Necklace-Cargo-Net, was made for Collective’s City Dome space, and bisects it dramatically like a great sail, and slightly like a huge flat fish.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn terms of scale alone, it’s impressive, particularly when considering the man hours involved in hand-tufting something so large. Colours hint at flower and leaf-like forms, though the clearest markings are the ropes of the cargo net which frame the shape. Patterns don’t repeat and forms are rarely resolved; it has the energy of a drawing, of improvisation.

Newby is also very much concerned with process and has, like Borland, produced a newspaper to accompany the show. Ornaments & Crimes: An Operating Manual for Drawing with Carpet explores his process in some detail, as well as how his work relates (or doesn’t) to the processes of industrial carpet-making. Like the work itself, it’s an ongoing enquiry, dynamic but unresolved.

Advertisement

Hide AdTextiles are important, too, in Sekai Machache’s The Divine Sky at Stills. Machache is one of the emerging artists supported by the gallery in its Projects 20 programme, and a winner of the RSA’s Morton Award. This body of work is the result of an 18-month fascination with indigo dye, made from the indigofera plant which is native to West Africa. The show’s title is taken from the poetic names given to the 12 stages of the dyeing process.

Machache has painted with indigo dye on paper and extensively on fabric, which has then been used to make an elegant colonial-era gown and feathered headdress which she wears as a costume in her performance. A collection of striking photographs show her emerging from layers of dyed fabric, and poised in a fine interior lighting an indigo coloured candle.

The culmination of the show is a rather beautiful 16-minute film in which she appears in costume in a Scottish moorland. A poetic text weaves together a narrative about her own identity as a member of the African diaspora, from a place of erasure (“I’ve been here all my life”) to a place which reconciles contradictions and emerges empowered.

Machache is a collaborator of Alberta Whittle, who will represent Scotland at next year’s Venice Biennale and was one of the artists to benefit from last year’s Tate bursaries in place of the Turner Prize. She is also one of the performers in Whittle’s film, RESET, which she made after winning the Frieze Artist Award in 2020, and which is being shown at Jupiter Artland now as part of a new installation.

There are common threads in their work: Whittle also embraces hard questions about race, slavery and colonialism but always returns to the theme of healing. In RESET, the juxtapositions are dramatic: she collages footage of angry clashes between Black Lives Matter protesters and police with the mourning ululation of singer Christian Noelle Charles and the performance of dancer Mele Broomes, who carries the weight of the film’s narrative from a place of confinement and exhaustion to a kind of goddess-like empowerment.

It is a response to a specific period of time, the summer of 2020, which saw Whittle stuck in Barbados as borders closed making a film with her collaborators in Scotland. It celebrates collaboration, and the importance of like-minded friends in a time of isolation and political trauma. A group show of the collaborators on the project (Machache included) is being held in Jupiter’s Steading galleries.

Advertisement

Hide AdSeeing this work in the ballroom at Jupiter Artland, next to the garden in which some of its most striking scenes were filmed, feels like coming full circle, a point of resolution at the end of a trying time. A quieter work in the nearby doocot uses the poetry of Barbadian Kamau Brathwaite to invite us into a private space of reflecting on what we have lost.

It seems to me that artists such as Whittle and Machache are moving contemporary art into a different kind of space. After decades of a dominant trend emphasising concept and theory, of artists distancing themselves from the idea that art can be beautiful, carry wisdom or be generally good for the soul, these artists are daring to move in precisely that direction. Starting from a personal place of negotiating their identity as women of colour, they are using the same techniques to frame some difficult questions and suggest ways forward which might be helpful for the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdChristine Borland until 3 October; Christian Newby until 29 August; Sekai Machache until 18 September; Alberta Whittle until 31 October

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions