Book review: Alan Davie in Hertford, by Mark Hudson

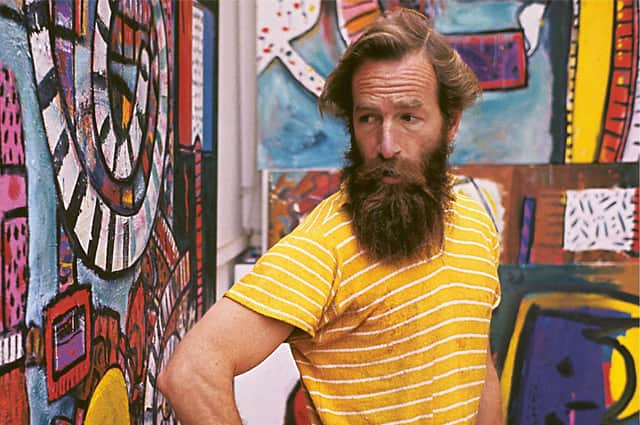

There can be little doubt that Alan Davie was one of the most significant Scottish artists of the 20th century. His work is held in major collections all around the world, from the Art Institute of Chicago to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and the Hepworth Wakefield. In 1956, when Davie had his first US exhibition at New York's Catherine Vivano Gallery, Jackson Pollock reportedly looked at his painting Goddess of the Green and remarked "I know exactly what he means." In the 1960s he made regular appearances in the newly-created colour supplements of the London papers, and a few years before his death in 2014, Patrick Elliott, senior curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, described him as "one of the top three or four living Scottish artists."

For all the fame and acclaim, however, from an art historical point of view Davie remains a somewhat problematic figure, in that his work defies easy categorisation. As the art critic Mark Hudson points out in this very readable and cogently argued reappraisal of his output, part of the difficulty is that Davie appears to have led an artistic life of two very different halves. In the 1950s and 60s, his huge, energetic and apparently abstract canvases seemed to fit under the umbrella of Abstract Expressionism; from the mid-70s, however, he was producing more figurative works, in which he set out to explore ideas of universal symbolism, incorporating the visual language of various different cultures. As Hudson puts it, this later work "seemed not only out of step with the increasingly conceptual currents of late 20th century Western art, but to actively refute the modernist principles on which his earlier critical success was based." Davie failed to see any distinction, arguing that his paintings from these two periods were "the same thing."

Advertisement

Hide AdBorn in Grangemouth in 1920, Davie trained at Edinburgh College of Art before manning anti-aircraft batteries with the Royal Artillery during the war. On demob, he enrolled on a teacher training course in Edinburgh where he met his wife-to-be, Bili. In the early 50s the couple moved to Rush Green near Hertford (handy for London, where Davie initially made a living playing in various jazz bands) and they bought a stable block and set about converting it into a house and studio. The home they made there became known as Gamels Studio, and it was to become the centre of Davie's creative universe for the next six decades.

When I visited Davie there in 2009 to interview him for The Scotsman, it was clear that the whole house, not just the large, airy studio, was part of his creative practice: the kitchen alone contained enough masks and figurines from all around the world to stock a small museum. If Davie was attempting to tap into some kind of primal spiritus mundi in his work, these objects surely had role to play. And it's this desire to locate and harness some universal creative force, Hudson argues, that unites Davie’s earlier and later work – as he puts it: “Davie's belief in the spiritual totality and interconnectedness of all art."

Hudson's book has been released to coincide with the creation of a new Alan Davie Collection at Hertford Arts Hub. Drawing on works that remained in Davie's various painting stores at the time of his death, Hudson suggests that, when displayed in one place, this body of work will help to dispel the idea of some sort of break between his earlier and later output, and provide "a very different sense of Davie's art: of how it developed and what it means."

"Looking [at] the totality of Davie’s work,” he writes, “it is exciting… to observe the freedom [with which] key tropes, concerns, images and ideas recur and reassert themselves over the decades. Images and gestures [from the 50s] are echoed in small drawings executed in his final weeks. For Davie, they existed outside time.”

Alan Davie in Hertford, by Mark Hudson, Unicorn, 112pp, £30.