Art reviews: Zarina Bhimji | Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran | Billie Zangewa | Joan Eardley

Zarina Bhimji: Flagging it up, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: Idols of Mud and Water, Tramway, Glasgow ***

Billie Zangewa: A Quiet Fire, Tramway, Glasgow ***

Advertisement

Hide AdJoan Eardley: Early Eardley, selected works 1940-1950, Reid Gallery, Glasgow School of Art ****

The lure of abandoned buildings has made a subgenre in photography: gorgeous light falling in empty, decaying rooms, a kind of beautiful melancholy. There is a whiff of this about Zarina Bhimji’s films which seek out disused, semi-derelict places, places without people, although traces of past human presence are never far away.

Waiting, made in 2007 when she was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, is a lingering look at a disused sisal factory in Kenya, a contemplation of rusting machinery, dust motes shimmering in shafts of sunlight and twists of residual fibres, which look like fine, pale hair. There is no narrative or explanation, what it evokes for the viewer is up to us: loss, perhaps, or memory, or some thoughts about industry or colonialism.

Bhimji last exhibited at the Fruitmarket in group shows in the 1980s. She was an emerging voice then, a new graduate working with photography, text and installation. Film came later, in 2002, when she made Out of the Blue for Documenta 11. Made in Uganda, it is also an evocation of place: a lush, coastal landscape, what might be a disused prison, prefabricated buildings which look like they’re being squatted, with sleeping mats, washing lines and, on one occasion, disconcertingly, a row of rifles propped against a wall. The soundscape is rich, from humming insects to crackling radios, but there is no exposition. We must put aside our curiosity for "where?” and “why?”

Fruitmarket’s ground floor gallery houses two works made 35 years apart: She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence’ (1987) is an installation in which photographs and text are suspended between layers of perspex over a carpet of colourful spices. This is clearly about migration – there is a Home Office stamp and a pair of surgical gloves alluding to searches and examinations. There are references to “wakeful wrathful women” and “white people [who]…laughed at their Indianness”.

Next to that is Blind Spot, a new work commissioned for this show. Here, the camera lingers in and around a semi-derelict house, all chipped paint and stripped-back plaster. This time, there is a voice, a fragmented (fictional) narrative about a refugee family torn apart as parents grew resentful of how western their daughter had become. It’s a powerful evocation of emotion through place, a meditation on the nature of home, and a reminder that certain issues are no less thorny and complex than they were three decades ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe work of Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran at Tramway approaches the concept of multicultural society in a completely different way. Nithiyendran fled Sri Lanka for Australia with his family as refugees in 1989. His playful, idiosyncratic visual language of gods and idols owes something to the fact that he exchanged one cultural and religious melting pot for another. Postmodernism, one suspects, did the rest.

His ceramic figures, multi-limbed and many-eyed, take something from Hindu deities, but to this he adds a contemporary edge, a streetsy aesthetic which places them somewhere between a Hindu temple and a particularly surreal episode of The Simpsons. His production values are hybrid too: some elements are highly finished, others left deliberately rough and ready. The colour tends to look like it’s been applied with a scatter gun.

Advertisement

Hide AdSome of the most successful installations in Tramway 2 are the ones which take on the large space as a whole, and Nithiyendran is not afraid of scale: a huge “guardian” figure made from mud and straw stretches almost to the ceiling, fountaining water from both hands and a pipe in its mouth. Next to it is a wonderfully makeshift building, constructed from recycled wood, bamboo, plastic sheeting and who knows what else, housing some 97 rough-hewn terracotta figures, all different, with details picked out in kitschy gold. Everything is lit like a theatre set.

But, for all the energy and ambition in this show, it feels oddly devoid of meaning. The point of a statue of a god, or any totemic figure, is that people imbue it with meaning. That’s what gives it its significance. These 21st century gods are somehow anti-totemic. They are diverse and multifarious, operating in a world where identity is provisional and everything means what you want it to mean. Which is, quite possibly, nothing at all.

There is more deliberate, serious intent in the work of Malawian artist Billie Zangewa in Tramway 5. Zangewa began her career in the fashion industry and now makes intricate fabric collages exploring subjects relating to Black femininity. Seven of these, from the last 15 years of her practice, are presented in this show.

She depicts scenes from ordinary life: a child sleeping, a woman trying on a dress in a bathroom, two people on sun loungers in an otherwise empty poolside resort. The fabric collaging is skilful and interesting, particularly her approach to skin tone, which makes use of a wide variety of hues in a single figure.

The key to reading this work is in the gaze. Zangewa’s women are either looking at themselves (like the woman in the bathroom) or deliberately oblivious to the external gaze (like the elegant woman reclining on a tree branch, which is surely a self portrait). The white man in Game stares out of the picture in challenge, even menace. In The Inquisition, which references the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the all-white family look straight out in a line, while their black woman guest is almost edged out of the frame. We become vividly aware of our role as viewers, and the judgements we might make.

Meanwhile, Glasgow School of Art offers us a pre-Christmas treat with a glimpse of the earliest work of Joan Eardley, mainly drawings from her time at art school in the early 1940s and from travelling scholarships from GSA and the RSA in 1948-49. Some are more successful than others; we see her getting to grips with drawing the human figure. What is clear is her commitment to the importance of drawing, her recourse to it as an immediate tool, using whatever she had to hand, and the gradual emergence of a fluent, confident line. Her study of a near-naked young woman in an armchair is sensual, even erotic in its power.

Advertisement

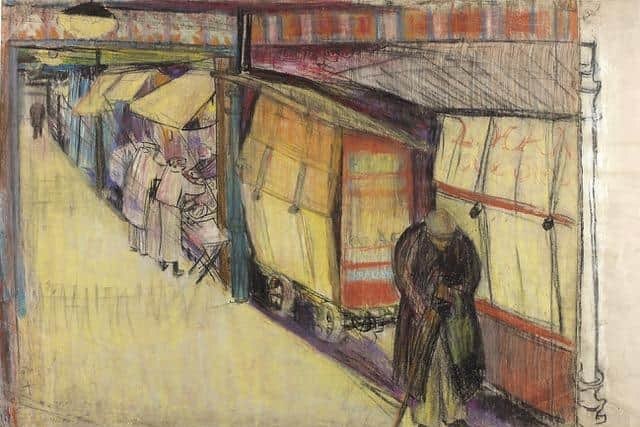

Hide AdWhat becomes clear (perhaps with the exception of the woman in the chair) is that Eardley’s eye is not drawn to what is classically beautiful. She draws carts under a tree, a broken wheelbarrow, an old man shuffling through the covered market at the Barras. Her Italian Farmhouse has a plough in the foreground. Even in Venice, she sketches in the back streets and in a dark corner of the Basilica of San Marco, where three solitary individuals are at prayer.

This is Eardley before Eardley, before she settled to the subject matter for which she became best known, though her superb drawing of a man mending fishing nets, perhaps in the Mediterranean, seems to prefigure the nets she would paint on the beach at Catterline. Even if it’s sometimes an uneven show, one is left, powerfully, with the sense of an artist absolutely committed to getting on with the job in hand, developing her skill and vision.

Zarina Bhimji until 28 January; Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran until 21 April; Billie Zangewa until 28 January, Joan Eardley until 16 December