Art reviews: William Wilson | Conversations with the Collection | Dennis Buchan

William Wilson: Print, Paint, Glass – An Anniversary Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh *****

Conversations with the Collection, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

Dennis Buchan, Compass Gallery, Glasgow ****

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Come up and see my etchings!” The motive of this legendary lecherous invitation was certainly improper, but the etchings might have been real enough. In the late 19th century, led by Whistler, there was a great revival of etching and they became a major commodity for artists. The reputations of Scots like Muirhead Bone, DY Cameron and James McBey depended largely on their prints. But the market was a bubble and, with the Wall Street Crash in 1929, it collapsed completely. In Edinburgh, however, the master etcher ES Lumsden, author of The Art of Etching, published in 1924, was determined that the art itself should not be lost, and on becoming president of the Society of Artist Printers in 1931 he worked hard to encourage the younger generation to keep the art going. William, always known as Willie, Wilson, was among those whom he both inspired and mentored. William Wilson: Print, Paint, Glass – An Anniversary Exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy gives a fascinating account of Wilson’s outstanding work as a printmaker, mostly during the 1930s, but as the title declares he was also distinguished for his watercolours and stained glass.

Wilson began his career in 1920 in the stained glass company of James Ballantyne. At the time, evening classes for trade apprentices were a major part of the curriculum at Edinburgh College of Art and, attending the college, Wilson was spotted by Adam Bruce Thomson. Encouraged by Thomson, in 1932, and taking leave from Ballantine’s, he enrolled full time at ECA. No doubt inspired by Lumsden, he had already started to make prints in the 1920s and before he enrolled at the college, he had travelled round Europe making drawings of places like Siena and San Gimignano in Italy and Toledo, Avila and Ronda in Spain. Back in Edinburgh, these were turned into magnificent prints. The RSA has inherited a number Wilson’s plates and so here we can see, side by side, the drawing, the copper plate and the finished etching of his superb prints of Toledo, for instance, or of the Bridge of the Scaligers, Verona. The Academy has also commissioned contemporary printmakers to take impressions from the plates and these are clearly identified as prints “after” Wilson.

Already in these prints dating from 1932 or ’33, his vision is distinctive. As though in response to the collapse of the etching market, several printmakers turned to the tightly disciplined and laborious art of engraving. One of Wilson’s early works here is an engraving of St Monance, for instance, and in his mature work he kept some of that discipline. There are no slick and easy lines in his prints. Everything is clearly and beautifully structured, yet it is alive with energy. This is nowhere more apparent than in prints that he produced later in the decade like North Highland Landscape, or Talisker, for instance. In them, the structure and drama of the landscape are so powerfully drawn and rendered in dramatic light and shade that you feel them almost physically.

For whatever reason, however, Wilson seems to have stopped making prints soon after the outbreak of war. He had begun exhibiting watercolours at the RSA in 1936. They became an important part of his work and the middle section of the show is devoted to them. In early examples like a painting of Salisbury Square, London, from 1936, the careful finish is still like the drawings he did in preparation for his etchings. Soon, however, he developed a vigour and strength of contrast in his painting which is unusual for the medium. There seems to have been a bit of a hiatus in his work during the war and from 1942-5 he served in the Auxiliary Fire Service, but his watercolours from the 1950s, of Paris, for instance, or a superb view up the Lawnmarket from a perch somewhere on top of St Giles, have all the drama of his best prints.

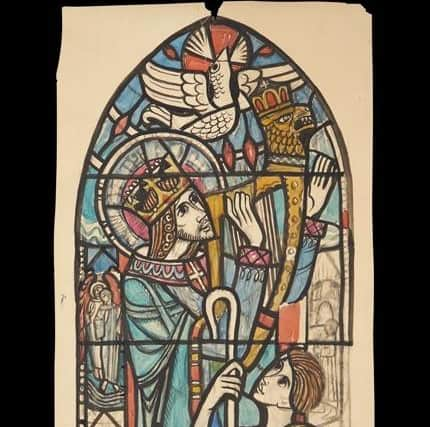

Wilson’s leave from stained glass making was protracted, but immediately after the war he set up his own stained glass studio and went on to become one of the outstanding artists in the medium in Scotland, and indeed further afield. He and his studio carried out more than 1,000 commissions over the following years. The last part of the show brings together a fascinating group of full-size cartoons and other preparatory work for a small part of this prodigious output. Stained glass is not a movable medium, but two small examples here give a sense of the strength of design and drawing and the intensity of colour that he brought to it.

There is a clear affinity between Wilson’s work in these three different fields. The colour in his watercolours often gleams like stained glass and the drawing in his prints can be like the lines of its glazing and, too, one of his most beautiful prints is of St Monance. There is fishing tackle in the foreground and the sun is rising behind the ancient church. It is a truly spiritual image and this quality, too, is apparent in his glass. He really was an outstanding artist. Tragically though, in his last years he lost his sight to diabetes. He died in 1972, aged 66.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe closest we get to Willie Wilson in Conversations with the Collection, the new hang of the first floor of Modern One at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, is two coloured woodcuts by Mabel Royds and beside them a lovely still-life by Anne Redpath. Royds was married to ES Lumsden and Redpath was a close friend of Wilson. Generally the company is very mixed, however, but the point of this hang is to bring about odd juxtapositions. The works are not organised by chronology, school or any other simple category, but by theme. Thus Mabel Royds and Anne Redpath’s works hang among other things near Mona Hatoum’s giant kitchen slicer, a still-life by Morandi and some black windows by Anna Barriball, all under the general heading of “Hearth”. Other headings like “Selfs” and “Stand-ins” bring Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Alison Watt and Sarah Lucas together with several others. Lucas photographs herself with a large salmon under a sign about public conveniences. There are some lovely things here, and some pretty awful ones. It is all a bit higgledy-piggledy. I don’t know why, for instance, there are more works by Prunella Clough than by anybody else. The labels declare themselves jargon free. You feel in the syntax what a struggle that has been, but they still tell you things that seem doubtful at best. When you are looking at a Louise Hopkins map, for instance, you are told that “she conjures up new land masses where they don’t exist.” Now that would be something.

Meanwhile, the Compass Gallery in Glasgow has kept the flag flying for good art for many years. The current show is a retrospective of the vigorous work of veteran Scottish artist Dennis Buchan. Like so many of this generation, he is not represented in the national collection, but he should be.

William Wilson until 13 November; Conversations with the Collection until 2025; Dennis Buchan until 21 October