Art reviews: Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: Paths to Abstraction | Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: Paths to Abstraction, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle ****

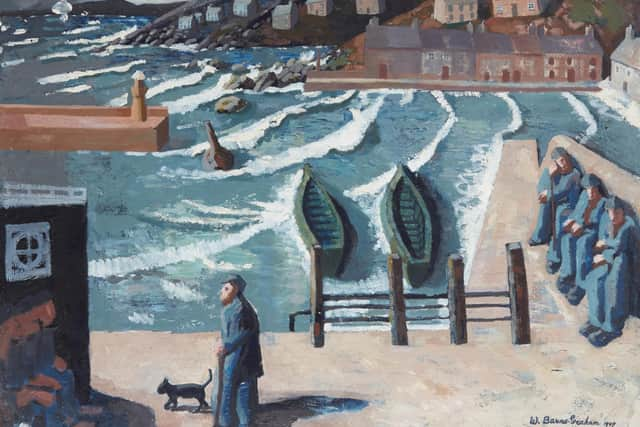

Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey, Aberdeen Art Gallery ****

Advertisement

Hide AdIt's rare to see an exhibition which charts an artist’s development as carefully and insightfully as the new show at Newcastle’s Hatton Gallery mapping the first half of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s long career. The vast majority of these paintings – around 70, making this the biggest Barns-Graham show for 30 years – come from the collection of the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust which now manages her legacy. If, at times during her life, she was dismissed as a lesser member of the St Ives school, the Trust is seeking to establish her reputation as a pioneering and distinctive modern artist in her own right.

Barns-Graham grew up in St Andrews and graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 1937. When stirrings of war in Europe prevented her taking up a travel scholarship abroad, on the advice of ECA principal Hubert Welling she headed instead for St Ives, then home to a group of artists including Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo.

The three pre-St Ives paintings here confirm that she was already a confident landscape painter, and she continued in that vein in Cornwall. Soon, however, the works show her exploring other forms of representation: the strong angular shapes of pitched roofs in the snow, or the multi-layered approach of a painting like Sleeping Town (1948). In Box Factory Fire, painted in the same year, she creates a conventional landscape but the twisted wreckage inside the burned out building is abstracted in form. It’s not entirely successful but is, perhaps, all the more interesting for that, the bones of the artistic experiment laid bare.

The interest in depicting both inside and outside was at least one of the factors at work in her remarkable epiphany the following year, when she visited the Grindelwald glacier in Switzerland. She drew it obsessively in the months which followed, but the paintings which gradually emerged did more than describe the forms – they looked into and through them, painting not just what she saw but the total experience of being there.

It’s often said that Barns-Graham came back from Switzerland an abstract painter. This is partly true, but it wasn’t an overnight transformation – she moved into and out of abstraction, as if testing its edges. While paintings such as White Square show a clear brush with constructivism, she was also painting rock forms in Cornwall in the 1950s which retained a sense of horizon, the barest bones of landscape. Snow at Wharfdale, painted in Yorkshire in 1957, is still a landscape, albeit one with a geometric pattern of fields and drystone walls. Red Painting, done in the same year, is a fractured abstract which seems to slash up the picture plane, an internal landscape, perhaps, painted at a time of loss and turmoil.

The largest of the five rooms brings together her 1960s work in a purer abstract style of geometric shapes and bold primary colours. Some explore movement through arrangements of paper squares which she set up in her studio and then painted. At one stage, she tried working compositions out mathematically, but they lacked life and fluidity and she returned to more free-flowing forms. Some seem purely about form and colour while others hint at an internal journey: Pilgrimage or Meditation East No.4. A further room charts this shift in miniature, tracking the colour red which had particular significance for the artist who was synaesthetic.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s a fascinating journey. The only regret is that it comes to rather an abrupt halt in 1972. Barns-Graham, of course, went on to have another 30 years of painting, including a remarkably productive period in her final decade. The plan is to tell that story, too, eventually, but we must be patient and appreciate what we have until then.

Another artist whose reputation is undergoing some revival is James McBey, born in rural Aberdeenshire in 1883, who went on to become one of the leading printmakers of his generation, drawing comparisons to Rembrandt and Whistler. A new biography, Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey, by journalist Alasdair Soussi, aims to help bring his work back to more widespread attention.

Advertisement

Hide AdA small show on the ground floor at Aberdeen Art Gallery, co-curated by Soussi, aims to capture attention with his remarkable life story. The illegitimate son of a blacksmith’s daughter, McBey taught himself etching while working as a bank clerk in Aberdeen. He became a celebrity in London and New York, fetching record prices for his prints, and worked as a war artist on the Middle Eastern campaign of 1917-18, painting the portrait of (among others) Lawrence of Arabia. Aberdeen Art Gallery holds one of the largest collections of McBey works and archive material in the world.

There is room, here, for just a taster of his work: evocative sketches of his mother and grandmother, watercolours of the Middle East and Venice, Scotland and Morocco, a sketch for his portrait of TE Lawrence, and the superb oil portrait of Vessie Owens, a young black girl whom he painted in North Carolina in 1946, newly acquired by the gallery.

The appetite thus whetted, the viewer must go upstairs to Gallery 13 where further McBey works from the gallery’s permanent collection give a stronger indication of just how good he was. Here, there is a portrait of his grandmother which recalls Rembrandt’s portrait of his mother, accomplished portraits of himself and his wife and of several of the other women in his colourful life, charcoal and watercolour sketches done on the hoof in the desert.

But it is the etchings which really astonish: the delicacy of touch in Dawn, The Camel Patrol Setting Out, which briefly, in 1926, held the record for the sale of a print by a living artist; the evocation of mood in Disquietude (Portrait of Mrs Martin Hardie), reminiscent of Munch’s prints, though with more restrained melodrama; the virtuoso skill in his renderings of Venice, all smokey light and water and ancient brick, conjuring subtleties the medium scarcely seems capable of. These are just a fraction of the McBey legacy, but surely, if they tell us anything, it is that he deserves further attention.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: Paths to Abstraction, until 20 May; Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey, until 28 May