Art reviews: Victoria Crowe | Joan Eardley | Iona Roberts

Victoria Crowe: Another Time, Another Place, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Joan Eardley The Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

Iona Roberts: Her Revolution, Kilmorack Gallery, Beauly ****

Advertisement

Hide AdWhat is it about twilight? It is a time for reflection perhaps, a moment when the earth’s rotation as it counts out the days is almost tangible. Nevertheless, most painters prefer to paint daylight. There are, however, also some remarkable artists for whom the appeal of twilight seems to have been irresistible. We think of Caspar David Friedrich, for instance, of his Norwegian associate Johan Christian Dahl, or of Samuel Palmer. Near contemporaries, they are Romantic artists with a capital R. But the Romantics have no monopoly, and Victoria Crowe seems to have been moving to join them in their appreciation of the poetry of twilight for some time.

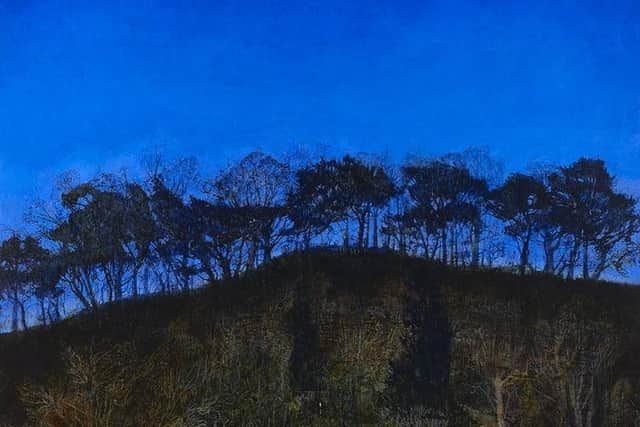

Indeed, her show at the Scottish Gallery, Another Time, Another Place, is mostly about twilight, but also more particularly, about winter twilight, a point she shares with Friedrich. Like his, too, these are pictures of intense mood. In November Stillness: A Puff of Smoke, for instance, bare trees are silhouetted against a deep blue, twilight sky. Beneath, the patterns of bare trees are half legible in the shadows of the November evening. To the left, the windows of a house make two points of warmer light while the puff of smoke rises white from an unknown source, a hidden bonfire perhaps. The picture does remind me of Samuel Palmer, but Palmer’s twilights are warm and a little sexy. This is more austere and reflective, but very beautiful too. So is The Amazing Clarity of the Night Skies. Again, trees are silhouetted against a deep blue sky. The new moon with an attendant planet is visible high up to the right, but beneath the hill enough of the light of day lingers to give a little patch of light among the trees. There is a drawing in ink and wash of a similar line of trees among a small, but fascinating display of drawings and notebooks.

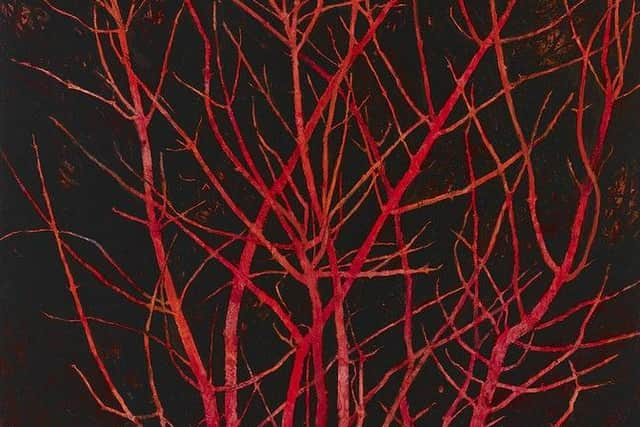

The light of the setting sun catching the bare branches of winter trees and seeming to set them on fire with its colour has been a frequent motif in her recent work and there are several dramatic examples here. Coral Bark, Maple and Moon is especially lovely. The sun has turned the branches of a tree to brilliant coral pink, but, above, the full moon rises over the ragged line of the wood.

Winter itself seems to be the subject of several pictures here. Frost Light, for instance, is not exactly a picture of twilight, but rather of the low light of the midwinter sun seen through the twisted branches of frosted trees. Making All Things New is a similar view of the winter sun through trees, but now reflected in the weathered silver a many-paned antique mirror. It is a beautiful pun on the two meanings of reflection, mirrored light and leisured thought. Indeed, she repeats it as if to underline the point in Light and Reflection from Within. The picture is a view from the windows into her garden in winter, but she is herself also reflected in the window, contemplating the scene. This is an elegant picture of both meanings of reflection. A hint at what she is perhaps reflecting on is given in Shadow Flying over Snow. This is an austerely beautiful painting that sits a little apart from the others here. It shows a snow-covered hillside etched with the patterns of winter trees and the lines of field margins. There is no sky visible. The hill fills the composition. Only a hint that shadow is rising up the hillside from below suggests the movement of the day towards evening. Hinting at memories, it is a picture whose mood and composition seems to echo some of the artist’s earliest responses more than 50 years ago to her new environment when she first moved from leafy Kingston-on-Thames to live beneath the austere, winter landscape of the Pentland Hills. Reflection is perhaps the theme of this whole lovely show.

The 18th of May 2021 is the centenary of Joan Eardley’s birth. She, like Victoria Crowe, came to Scotland from the south, but when she came to Scotland in 1968, Crowe had recently finished at the Royal College. Eardley arrived here as a teenager into wartime Glasgow. Radical ideas were circulating among the artists there and although it is nearly 60 years since her untimely death, her work still looks modern. A number of events are planned later in the summer to mark her centenary, but the Fine Art Society is honouring her actual birthday with a small show that opened in time for it.

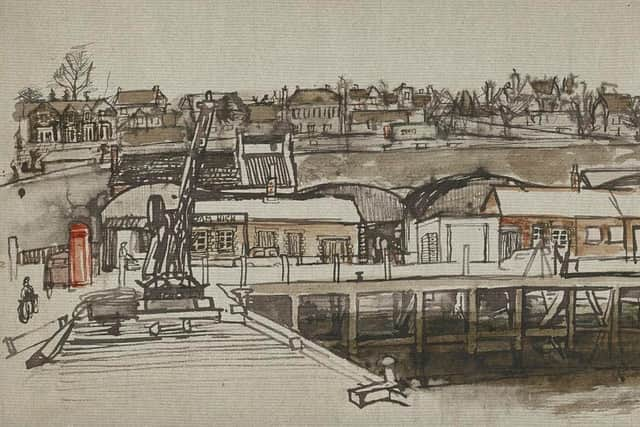

The show consists mostly of photos by Oscar Marzaroli of her at work in her studio and of the Townhead children who became her principal Glasgow subject matter, but there is also a group of paintings and drawings. A small watercolour of Arbroath Harbour is of historical interest as it was done when she was at Hospitalfield, the postgraduate art school run at the time by the four Scottish Colleges. James Cowie was then the resident teacher. There is also a striking pastel of two of the Townhead children, a boy and a girl holding hands. Her uncompromisingly unsentimental depiction of the children is startling, but the effect is the more compassionate as a result.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe lack of compromise may owe something to Cowie’s stern example, but photographs of her at work in her studio on similar pictures (there’s only one on the easel, but others nearby suggest she worked on several at once) shows them unfinished. Still nearly abstract, they look very like Jean Dubuffet’s contemporary and radical Art Brut. Indeed, like Dubuffet she did incorporate graffiti in some of her latest works. A lovely painting of Andrew, a boy who was the subject of several remarkable pictures standing alone, hands in his pockets, is a gentler image however. It is profoundly sympathetic and you can read in it how she knew and liked the boy.

At the Kilmorack Gallery, Iona Roberts, who graduated form Edinburgh College of Art in 2015, is a relative newcomer, but she already has a distinguished career. On show is a group of her vigorous drawings and a small number of paintings. She describes her drawings as mixed media, but they seem to be mostly pen and wash in sepia or black ink. There are several townscapes including a striking view Edinburgh. It has an added ghost and she does seem to favour graveyards, often with the moon in the sky – or in one landscape two moons, a touch of the Romantics perhaps. But these images have terrific energy so there is nothing maudlin about them, no self-regarding melancholy. In fact a breath of fresh air seems to blow through her graveyards, its freshness and vigour dispelling such thoughts.

Advertisement

Hide AdVictoria Crowe and Joan Eardley until 29 May; Iona Roberts until 20 May

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions