Art reviews: Turner in January | Ten Years of Modern Masters

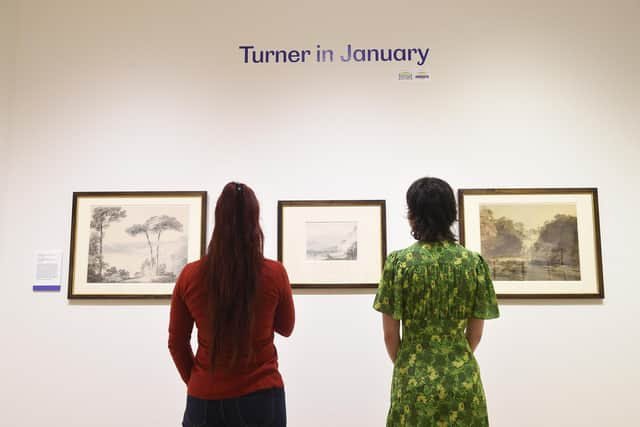

Turner in January, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh *****

Ten years of Modern Masters, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Henry Vaughan was a rich Victorian - his father had made a fortune from making hats, and he enjoyed spending it on art. Among much else he amassed a collection of some 200 works on paper by Turner including watercolours, drawings and prints. He knew Turner personally and bought directly from him. Vaughan’s life spanned most of the 19th century and when died in 1899, aged 90, he divided his collection into bequests to different public collections. Among them, in 1900, the National Gallery of Scotland inherited 38 Turner watercolours. Vaughan understood the fragility of the medium and its sensitivity to light (if you have any watercolours, don’t hang them in daylight!) and so he attached precise stipulations to his bequest. The pictures were to be shown all together and free of charge, but only during the month of January, when of course daylight is at its weakest. He also stipulated, however, that for the rest of year they were to be available for private study. And so, since 1901, this wonderful collection has been shown each January as a fixed and favourite part of the Edinburgh calendar, familiar perhaps, somehow always fresh to see, but also still looking fresh. Because Vaughan bought them directly from Turner himself and evidently respected his own stipulations about not exposing them to the light, they are in exceptionally brilliant condition. Turner travelled constantly, and so the scenes depicted range widely across the British Isles and Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdVaughan chose these pictures carefully to represent the range of Turner’s work in the medium, both in variety of scale and purpose as between informal sketch and finished painting, but also, as far as he could, in chronology. The collection begins with the cool work in near monochrome greys and blues that Turner did as little more than a boy in the last years of the 18th century, and ranges to the explosive dash and colour of his latest work. There is, however, a much greater emphasis on the later work, reflecting no doubt the fact that it was only in the 1840s that Vaughan got to know Turner.

Looking at the dramatic atmosphere of towering clouds and misty mountains in a painting like St Gothard Pass, The Devil’s Bridge, for instance, or a view jagged mountains at Schwyz, it is easy to think of Turner as he was described by one critic as painting "tinted steam”, or more cruelly by William Hazlitt, who said that his paintings were "pictures of nothing, and very like.” The individual pictures are so rich, however, that you can constantly see new things in them and I was struck this time by how precise he was, from the very earliest pictures here, defying such opinions – for instance, in a lovely study in grey wash of boats from the 1790s in Dover harbour. He had the gift of combining extraordinary attention to detail with real fluency. A drawing of a man o’war done 30 years later is just as precise. You could work out from it how the ship’s complex rigging worked, yet it is vividly alive. In a painting of the Rhine done around 1817-19, the detail of the boats and of the distant towns is meticulously observed. The picture is barely a foot across, but is not weighed down by this detail at all.

Even in his grandest watercolours, like a dramatic painting of the Alps towering above the Brenva Glacier in the Val d’Aosta, what is striking is the way that the whole surface is worked over. You can see where he has simply left a pool of wet paint to dry so its edges form part of the drawing, but then he has worked with a dry brush to give texture to the mountains. He’s never slap-happy and in a spectacular view of Heidelberg from 1846, perhaps the latest picture here, for all the breadth of his vision of the setting sun, figures in the foreground are quite clearly drawn even though it is not at all clear what exactly they are doing.

Minuteness becomes the point of the picture when he is working on a small scale on pictures to be engraved as book illustrations. These are true miniatures, vignettes barely a couple of inches high like two here done in the vicinity of Abbotsford. A radiant view of Melrose with the Tweed winding through the middle distance and the Eildon Hills beyond is only slightly larger and has the same delicate minuteness. A gift for Sir Walter Scott, a figure in the right foreground, evidently painting, is apparently a self-portrait of Turner himself.

A group of three paintings of different views of the Falls at Schaffhausen are masterpieces. They celebrate the grandeur of nature as few artists could and yet one of them was painted by moonlight. Among the loveliest things, however, is a vivd group of small paintings on blue paper. In a brilliant view of Coblenz, for instance, a distant white bridge is reflected in the water and the arches are defined by tiny touches of vermillion. The same minute touches of red give mass to the rock on which the town stands in the distance.

It is hard to understand how he managed such magic, working at once with such breadth and at the same time considering it all so minutely. In one of the most memorable of all these memorable pictures he pulled off an even more startling effect. It is a painting of the Piazetta in Venice lit by a flash of lightning. According to the label, he pulled this off by scraping through the paint with “his eagle-claw of a thumb-nail” to the white paper beneath to catch the bolt of lightning and the brilliant, instantaneous illumination of the façade of St Marks. But even this astonishing Venetian scene is matched by a painting of a black steam boat belching black smoke as it chugs though the misty lagoon. It must have inspired the opening scene of Visconti’s Death in Venice, testimony surely to the power of Turner’s imagery.

Advertisement

Hide AdLooking at Joan Eardley’s Winter Sea II at the Scottish Gallery, with the sun just glimmering through grey clouds above a wild sea, you can still see echoes of Turner. His legacy was immense. This picture is a star in a show marking ten years of the gallery’s exhibitions of Modern Masters. Among its companions are a beautiful study of a child sitting at a table, also by Eardley, and several paintings by her friend and follower Lilian Neilson. There is also a very grand painting of haystacks beneath a setting sun by Sir William MacTaggart which hangs beside a lovely watercolour by his grandfather, William McTaggart. Like Eardley and Neilson, James Morrison worked at Catterline and a painting here of fishing nets certainly recalls that experience, though it was painted after he had moved from Catterline to Montrose. In pictures like Egypt Angus or Old Montrose, you can also see how Morrison followed Turner in his ability to move from an immense sky down to the tiniest details of the landscape. There also several fine pictures here by David McClure, but among much else, Jenny’s Room by Victoria Crowe stands out as a particularly lovely study of the bedroom of Jenny Armstrong who inspired the artist’s memorable series, The Shepherd’s Life.

Turner in January until 31 January; Ten years of Modern Masters until 28 January