Art reviews: The Accursed Share | Sebastián Díaz Morales

The Accursed Share, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Sebastiàn Díaz Morales: Smashing Monuments, Collective, Edinburgh ****

A cost of living crisis might feel like the ideal moment to stage a major exhibition on the theme of debt, but Talbot Rice Gallery’s The Accursed Share takes a much more global view of the subject. Colonialism, imperialism, exploitation, oppression: these things usually begin and end with money, and debt is a key mechanism by which they are perpetuated.

Advertisement

Hide AdUnder director Tessa Giblin and curator James Clegg, Talbot Rice has staged some impressive themed group shows, drawing on the work of artists from around the world, often from beyond the predictable canon of Western Europe/North America. This one might be the most ideologically forthright, also including the first chance in Scotland to see the seminal work by Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid, Naming the Money.

The show is particularly ambitious given that its premise lies in economics (the title is from Georges Bataille). The question is: what can art bring to help us understand these issues better? Can it propose fresh ways of looking at them, or even, of doing them?

One thing at which the best contemporary art excels is the succinct act of visual transformation. For a case in point, see the installation by Sammy Bajoli, from the Democratic Republic of Congo, in which 50 copper mortar shell casings are repurposed as plant pots for native Congolese plants. It’s a swords-to-ploughshares moment which robs these objects of their power and leaves them looking not unlike a display from Ikea, while acknowledging a deeply serious history about copper mining and exploitation in DRC.

There’s another transformative moment later in the show with Hanna von Goeler’s Migrations series, meticulous studies of birds painted on defunct bank notes. Obsolete currency is reborn as art (though, sadly, the majority here are prints, not originals), set free to transcend national boundaries as the birds do (and currencies do not). Some are endangered species. Others have been selected to tell a story of human migration, like the Syrian serin, painted on a Greek note. A grey wagtail, a new commission for this show, painted on a Scottish pound, is a bird which was traditionally seen as a premonition of ill, particularly at the time of the Clearances when Scotland faced the kinds of issues which are featured elsewhere in the show.

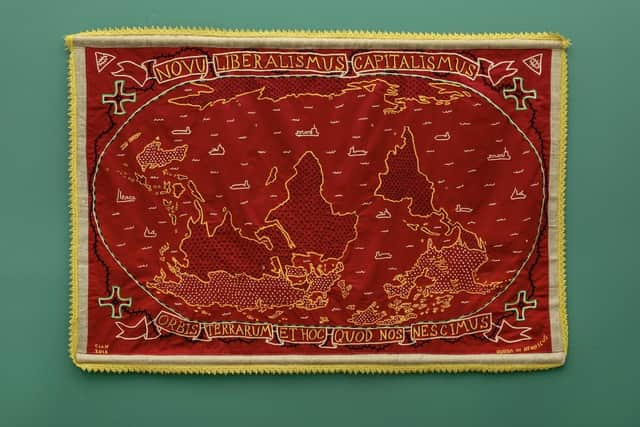

Some of the work is deliberately didactic. Cian Dayrit, working in collaboration with marginalised communities in the Philippines, spells out the systems which perpetuate inequality in these islands, bolstered by neoliberalist agendas. His assemblages of objects and trinkets in five house-shaped frames are particularly eye-catching.

Other artists make proposals for the future. Marwa Arsanios’ 35-minute film, Who is Afraid of Ideology? Part 4, Reverse Shot, explores the possibility of bringing back “mashaa” (common land) in Lebanon. She digs deep into the history and bureaucracy of land ownership in the country, pondering whether the damage wrought by colonialism, civil war and privatisation can be reversed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnglo-German group terrao seem to have found a truly radical idea in proposing to create a forest which, by AI technology, can issue its own sustainable logging rights and buy its own land, though there is no indication of how far (or if) the project has progressed past the starting blocks. Stockholm-based artists Goldin+Senneby take the land ownership bull by the horns buying a plot of wasteland above a former coalmine in Belgium. They have decorated the walls of the Round Room with designs from the fossils of a carboniferous forest they found on the plot, signalling a time which predates all ownership.

The idea of gentle, meticulous repair is put forward by Zagreb-born Hana Miletic, whose quiet works are dotted around the show. Inspired by homespun repairs to doors, windows, pavements, wing mirrors, she recreates them in hand-made woven textiles, though they don’t demand the attention visually which her meticulous work deserves. Moyra Davey’s Copperheads are macro photographs of one-cent coins, showing how they have aged and tarnished. Strangely, as the work in the show which addresses money most directly, it is also one of they few flat notes.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe curators have kept one of the most engaging pieces until last. In Naming the Money (2004), Lubaina Himid took the black figures found in the background of European court paintings and gave them independent lives as lifesize wooden cut-outs. Their sheer numbers, in the Georgian Gallery, give them a kind of force. She then gave each a name – an African name as well as a generic European name by which they would have been known – and a backstory. These stories form part of the soundtrack, which also includes music.

This is another act of transformation: men and women – servants, dancers, musicians – who were themselves possessions, status symbols, a kind of currency, are given back their humanity. Their (fictional) stories embrace loss, but also their ability to adapt, survive and view their new circumstances with a degree of equanimity. It’s a supreme act of imaginative redemption.

The new exhibition at Collective also offers a non-Western perspective which is surprising in its gentleness. In his 40-minute film, Smashing Monuments, Argentine artist Sebastiàn Díaz Morales worked with the Indonesian art collective ruangrupa, who were the artistic directors of last year’s Documenta 15, where this film also premiered.

Morales’ film shows members of ruangrupa at large in their home city, Jakarta, striking up conversations with the city’s statuary. Monumental in scale and modern in style, these were mainly constructed in the 1960s when Indonesia was forging its identity as a newly independent, modern nation. But, contrary to what the title suggests, there is no willful destruction.

We see the artists address conversationally these larger-than-life figures, most of which seem now to sit in the middle of busy motorway intersections. Ade Darmawan asks the Pemuda Membangun statue (a celebration of youth) what he makes of youth today. The statue’s part of the city is now so gentrified no young people can afford to live there, but “you should come down and hang out with us some time”.

Farid Rakun introduces his baby daughter, Naga, to the Pembebasan Irian Barat Statue, built to celebrate independence from the Dutch. Addressing “Uncle Jaya” while rocking his sleeping baby in his arms, he ponders her future in a world where the West is gradually becoming less important.

Advertisement

Hide AdGesyada Siregar has a poignant conversation with the Tugu Tani statue, a mother graciously taking leave of her soldier son. She reflects on her relationship with her own mother, who died when she was a teenager, but walked to high school past this statue. Could the statue pass a message to her, across time, tell her that her daughter turned out okay?

It’s a warm, sometimes funny, occasionally moving film which steers clear of any political discourse about these statues or the Suharto regime under which most of them were built. Instead, it’s about how the figures who populate the built environment become part of life, bridging the gap between generations, fixed points in a transforming city and reference points for the changes in the citizens’ own lives.

The Accursed Share until 27 May; Sebastiàn Díaz Morales until 11 June