Art reviews: Society of Scottish Artists Annual Exhibition | Andrew Gannon

Society of Scottish Artists Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Andrew Gannon: Impressions, Fruitmarket Gallery ***

Since it’s Christmas, imagine a box of chocolates: the tantalising appeal of a newly opened layer, all those flavours waiting to be enjoyed. The Society of Scottish Artists Annual Exhibition, decking the sumptuous halls of the RSA this festive season, is a lot like that.

Advertisement

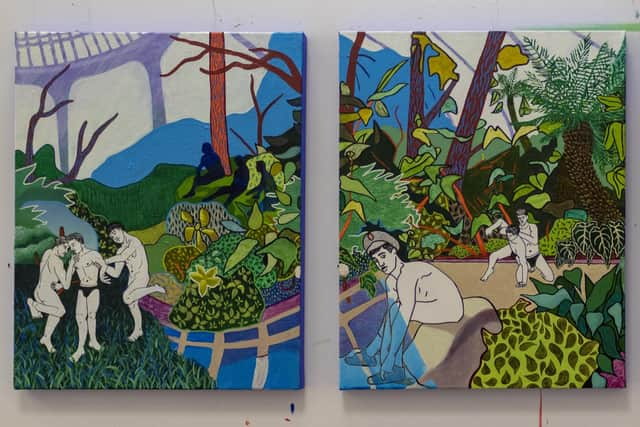

Hide AdThere are over 300 works, paintings, sculpture, printmaking, photography, film and installation, by almost as many artists, across every possible style. Artists a year out of college are hanging shoulder to shoulder with those well established. Where to go first? What flavour to choose?

The SSA is 130 this year, set up by a group of artists in Edinburgh in 1891. These frock-coated Victorians were the new kids on the block, seeking to give opportunities to younger artists and bring international names to Scotland. They did so with Edvard Munch in 1931, causing raised eyebrows in the city when they presented a selection of his work in 1931.

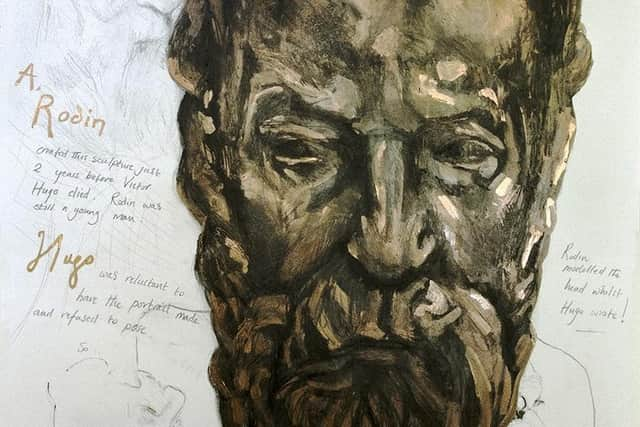

For the anniversary, the SSA has brought back a small number of works shown over the years: Rodin’s Head of Victor Hugo, which was shown at the first ever exhibition in 1892 (that show had 572 works, pity the poor critic!); Munch’s lithograph The Sick Girl; works by Cadell and Eardley and a gloriously subversive bronze, Locomotive Descending a Staircase, by George Wyllie, a one-time SSA president.

The Society then issued an open call for members to respond to these works in a contemporary way, attracting 90 submissions. Amy Dury reimagines Munch’s sick girl as a woman with an eating disorder, living with the tyranny of her mirror. Rachel Duckhouse responds to the geometric forms in a late painting by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in her own meticulous style. Jenny Pope responds to Wyllie (as he, in turn, responded to Duchamp) with a kinetic sculpture, Dangerous Descents, as quirky as it is serious, adorned with the textile paws of endangered species.

From the moment you enter the building, the emphasis is on the contemporary. It’s impossible to avoid Suffering, an immense pair of lungs by Yen-Hsu Chou, slowly inflating and deflating. No one can look at a pair of lungs these days without thinking about what the world has been through since 2020. Just a few steps inside, Hans Clausen’s banners made from NHS uniforms and patient gowns – Everyone a Carer, Everyone a Healer, Everyone a Patient – strike a powerful and poignant chord.

Eleven artists have been selected from this year’s graduates at Scotland’s art schools and some FE colleges. Most respond with ambition, letting their work stretch to fill these big spaces: Hannah Grist’s sculptures made from old radiators; Tilda Watson’s striking monochrome mobile; Sarah May Sanger’s sculpture about anxiety and public transport.

Advertisement

Hide AdOrkney-based Vicki Redpath-Watson uses the full height of the building for a cascade of paper imprinted by the movement of the body. Elijah Louis Smith takes a tongue-in-cheek look at the world beyond art school in his drawings. Textile artist Molly Kent, a 2020 graduate, was the winner of last year’s SSA Award for Outstanding Achievement, and presents a superb piece of woven tapestry about childhood trauma.

There is an international component too: Nicole Schlosser from Quebec and the work of Scottish-Norwegian collaborators Ebbe & Flow. Artists from around the world were invited to submit work for the film programme, curated by artist-run organisation CutLog.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt is also wonderful to see other recent graduates claiming their place on the walls, whether supported directly by the organisation or not: Siobhan McLaughlin’s mountain landscape painted on stitched-together fragments of canvas; Fanny Arnesen’s atmospheric trees; Oana Stanciu’s photographs; Becky Brewis’ drawings on pages of historic newspapers.

What to say of the rest? There is well-deserved commendation for the hanging team who have made visual sense out of so much diverse work, particularly in the beautiful arrangements of smaller pieces grouped harmoniously around tone and colour.

There are works that catch the eye: Alistair Mavin’s impressive large-scale mosaic made from postage stamps; Sharon Thomas’ much smaller but equally impressive portraits on eggs; Bronwyn Sleigh’s impressive installation made from steel and coloured thread which poses questions about shapes and perspective; a toytownish Brutalist Sculpture Park by Ally Wallace made from papier mache.

There is photorealism by Keith Epps, a large surreal citiscape by Alasdair Wallace, small, accomplished abstracts by Norman Sutton Hibbert, an ambitious landscape by Ruth Nicol. There’s printmaking by Gregory Moore, fine figurative painting by Graeme Wilcox (in a largely non-figurative show), photography by Gina Soden and Rebecca Milling, abstract constructions by Calum Hall and David Lemm. I could go on. Like the proverbial chocolate box, there is something for everyone. Please go, and pick your own favourites.

Meanwhile, Edinburgh-based Andrew Gannon has taken a sidestep from a performance-based practice into sculpture with recent work on display in Fruitmarket Gallery’s warehouse space. In late 2019, he began to make work for the first time which explored his disability (congenital limb difference), and the building blocks for these sculptures are plaster bandage casts – literally impressions – of his left arm.

The process is one which is used in preparation for prosthetics, a kind of constructed “normality” which is often (Gannon says) more for the onlookers’ benefit than for the wearer’s. These works are the opposite: they have no functionality, and attract attention rather than blend in; some are brightly coloured. As sculptural forms go, they are interesting, but repetitive. Having found a sculptural building block, Gannon doesn’t push its potential to see where it could go.

Advertisement

Hide AdAccompanying the show are “Drawing Limb” performances in which he attaches a piece of charcoal to his left arm using a bandage cast and a long cane, and sets about drawing a picture of one of the sculptures. It’s an exercise which seems to operate at the edges of control: even keeping the charcoal on the paper looks like a struggle.

This, one feels, is the heart of show for him. Whether the aim is to demonstrate the difficulty inherent in the act of drawing or to draw more fluidly (as Matisse did, drawing with a long cane) is unclear. Either way, the exercise is circular, almost absurdly so. Rather than being taken on a journey by the work, we feel we have ended up back where we started.

SSA Annual Exhibition until 10 January; Andrew Gannon until 8 January